Saint Patrick's Battalion

Consisting of several hundred mostly Irish and other Catholic European expatriates and immigrants, including numerous men who had deserted or defected from the United States Army, the battalion was formed and led by Irishman John Riley.

[1] Composed primarily of Irish immigrants, the battalion also included German, Canadian, English, French, Italian, Polish, Scottish, Spanish, Swiss and Mexican soldiers, most of whom were Catholic.

[5] Successive Mexican presidents have praised the San Patricios; Vicente Fox Quesada stated that, "The affinities between Ireland and Mexico go back to the first years of our nation, when our country fought to preserve its national sovereignty... Then, a brave group of Irish soldiers... in a heroic gesture, decided to fight against the foreign ground invasion",[6] and Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo stated "Members of the St. Patrick's Battalion were executed for following their consciences.

[8] The U.S. Army often recruited the Irish and other immigrants into military service shortly or sometimes immediately after arrival in America in coffin ships with promises of salaries and land after the war.

[citation needed] Numerous theories have been proposed as to their motives for desertion, including cultural alienation,[9][10] mistreatment of immigrant soldiers by nativist soldiers and senior officers,[11][10] brutal military discipline and dislike of service in the U.S. military,[10] being forced to attend Protestant church services and being unable to practice their Catholic religion freely[12] as well as religious ideological convictions,[13][10] [14] the incentive of higher wages and land grants starting at 320 acres (1.3 km2) offered by Mexico,[15][10] and viewing the U.S. invasion of Mexico as unjust.

[23] Mexican author José Raúl Conseco noted that many Irish lived in northern Texas, and were forced to move south due to regional insecurity.

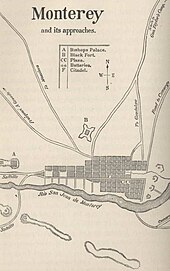

[32] At the battle of Monterrey the San Patricios proved their artillery skills by causing the deaths of many American soldiers, and they are credited with defeating two[33] to three[3] separate assaults into the heart of the city.

[36] They then marched northward after joining a larger force commanded by Antonio López de Santa Anna sent from Mexico City, the "liberating army of the North".

A small number of San Patricios were dispatched with a division commanded by Manuel Lombardini with the express purpose of capturing the 4th's cannons once the crews had been dealt with.

As the division got close enough they charged the artillery battery, bayoneting whoever remained and routing the rest, leaving the attached San Patricios free to haul away two six-pound cannons.

[7] General Francisco Mejia's Battle Report for Buena Vista described the San Patricios' as "worthy of the most consummate praise because the men fought with daring bravery.

It was renamed the Foreign Legion of Patricios and consisted of volunteers from many European countries, commanded by Col. Francisco R. Moreno, with Riley in charge of 1st company and Santiago O'Leary heading up the second.

[7] Desertion handbills were produced, specially targeting Catholic Irish, French and German immigrants in the invading U.S. army and stating that "You must not fight against a religious people, nor should you be seen in the ranks of those who proclaim slavery of mankind as a constitutive principle ... liberty is not on the part of those who desire to be lords of the world, robbing properties and territories which do not belong to them and shedding so much blood in order to accomplish their views, views in open war to the principles of our holy religion".

[51] Unlike the San Patricios, most of whom were veterans (many having served in the armies of the United Kingdom and various German states), the supporting Mexican battalions were simply militia (the term 'National Guard' is also used[46]) who had been untested by battle.

[53] When the requested ammunition wagon finally arrived, the 9 ½ drachm cartridges were compatible with none but the San Patricio Companies "Brown Bess" muskets, and they made up only a fraction of the defending forces.

[15] The San Patricios used this battle as a chance to settle old scores with U.S. troops: "The large number of officers killed in the affair was ... ascribed to them, as for the gratification of their revenge they aimed at no other objects during the engagement".

[57] Though hopelessly outnumbered and under-equipped, the defenders repelled the attacking U.S. forces with heavy losses until their ammunition ran out and a Mexican officer raised the white flag of surrender.

Officer Patrick Dalton of the San Patricios tore the white flag down, prompting Gen. Pedro Anaya to order his men to fight on, with their bare hands if necessary.

[7] American Private Ballentine reported that when the Mexicans attempted to raise the white flag two more times, members of the San Patricios shot and killed them.

[56][58] After brutal close-quarters fighting with bayonets and sabers through the halls and rooms inside the convent, U.S. Army Captain James M. Smith suggested a surrender after raising his white handkerchief.

[43] The Saint Patrick's Battalion continued to function as two infantry companies under the command of John Riley, with one unit tasked with sentry duty in Mexico City and the other was stationed in the suburbs of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

[69] One San Patricio was murdered by American soldiers when he was recognised among the prisoners of war in the aftermath of the Battle of Molino del Rey, by being thrown "into a mill flume and crushed by the wheel".

The Mexican government described the hangings as "a cruel death or horrible torments, improper in a civilized age, and [ironic] for a people who aspire to the title of illustrious and humane",[15] and by a writer covering the war as "a refinement of cruelty and ...

[77] George Ballentine remarked, in his account of his American military service in Mexico, "[T]he desertion of our soldiers to the Mexican army ... were still numerous, in spite of the fearful example of the executions at Churubusco, [and] also served to inspire that party with hope."

In Winfield Scott's 1852 run for President of the United States, his treatment of the San Patricios was brought up by his opponents to sway Irish American voters.

The unit was evoked in a Saint Patrick's Day message from Subcomandante Marcos of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation,[92] The San Patricios have been remembered as a symbol of international solidarity with Mexico.

It was that glorious Emblem of native rights, that being the banner which should have floated over our native Soil many years ago, it was St. Patrick, the Harp of Erin, the Shamrock upon a green field.According to George Wilkins Kendall, an American journalist covering the war with Mexico:[97] The banner is of green silk, and on one side is a harp, surmounted by the Mexican coat of arms, with a scroll on which is painted Libertad por la Republica Mexicana [Liberty for the Mexican Republic].

The first describes it as: ... a beautiful green silk banner [which] waved over their heads; on it glittered a silver cross and a golden harp, embroidered by the hands of the fair nuns of San Luis Potosí.

The second notes only: Among the mighty host we passed was O'Reilly [sic] and his company of deserters bearing aloft in high disgrace the holy banner of St. Patrick.A radically different version of the flag was described in a Mexican source:[100] They had a white flag/standard, on which were found the shields of Ireland and Mexico, and the name of their captain, John O'Reilly [sic] embroidered in green.Whatever the case, in 1997 a reproduction military flag was created by the Clifden and Connemara Heritage Group.

A third version embodying the description of the San Luis Potosí flag was made for the Irish Society of Chicago, which hung it in the city's Union League Club.