International sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

[1] Following the overthrow of Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević in October 2000, the sanctions against Yugoslavia started to be withdrawn, and most were lifted by 19 January 2001.

[7][11] On the following day, President George H. W. Bush of the United States ordered the Department of Treasury to seize all US-based assets of the Yugoslav government, worth approximately $200 million at the time.

[12] In spite of Mitterrand's amendment, Resolution 757 solely targeted the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, not any of the breakaway states.

Resolutions 820 and 942 specifically prohibited import-export exchanges and froze assets of Republika Srpska, at the time an unrecognized Serb statelet established by the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

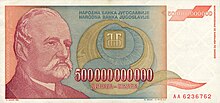

[15] Starting from 1992, the money supply of the Yugoslav economy grew enormously to fund the wars, resulting in a protracted hyperinflation episode which lasted for a total of 25 months.

[11] During the peak of the hyperinflation January 1994, the Yugoslav government recruited Dragoslav Avramović, a former World Bank economist, as an economic adviser.

[16] For several months afterwards, the money supply stabilised, so the dinar recorded virtually no devaluation, and shortages of various necessities were noticeably reduced.

[18] Avramović told The New York Times that he thought his fiscal program could be sustained in spite of the sanctions, saying the following: The currency is steady, we have achieved agricultural independence and industrial production is up 40 percent since the end of last year.

[17] Ljubomir Madžar, an economist, was quoted in the same NYT article as saying the following: Hard-currency reserves are not sufficient, production cannot achieve sustained expansion under an embargo, and so the budget deficit must grow by the end of the year, leading to new hyperinflation.

[21] As a result of the oil and gas restrictions imposed by the sanctions, owners of private vehicles in Yugoslavia were allotted a ration 3.5 gallons of gasoline per month by October 1992.

[22] By November 1992, the state had begun selling public gas stations to individuals in hopes of circumventing the sanctions on fuel.

[24] As a result, the safety GSP buses was gradually neglected, to the point in the late 1990s (after which sanctions had been re-introduced after the Kosovo insurgency started) where a passenger sitting over the one of the wheels on the bus fell through the rusted floor and was instantly killed.

[25] A Central Intelligence Agency assessment on the sanctions filed in 1993 noted that "Serbs have become accustomed to periodical shortages, long lines in stores, cold homes in the winter and restrictions on electricity".

[27] In October 1993, in an attempt to conserve energy, the Yugoslav government began cutting off the heat and electricity throughout residential apartments.

[31] In some cases they were an ideal target for various mafia groups, which could profit from killing smugglers and taking their cash intended to import gas into Yugoslavia.