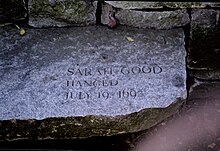

Sarah Good

The estate was divided mostly between his widow and two sons, with only a small allotment to be shared among seven daughters, however, even this was denied to the girls by their mother's new husband.

[1] The small portion of land that Sarah had received from her father's estate was lost in a suit filed by Poole's creditors.

When Samuel and Mary Abbey gave her lodgings for a time they said she was "so turbulent a spirit, spiteful and so maliciously bent" that they put her out.

[3] Sarah was of a lower economic status, reduced to poverty due to the inheritance customs which cut out daughters and the debt of her first husband, Daniel Poole.

She was accused of rejecting the puritanical expectations of self-control and discipline when she chose to torment and "scorn [children] instead of leading them towards the path of salvation".

When it had stopped, she claimed Good had attacked her with a knife; she even produced a portion of it, stating the weapon had been broken during the alleged assault.

However, upon hearing this statement, a young townsman stood and told the court the piece had broken off his own knife the day before, and that the girl had witnessed it.

She also said that Good had ordered her cat to attack Elizabeth Hubbard, causing the scratches and bite marks on the girl's body.

When Good was allowed the chance to defend herself in front of the twelve jurors in the Salem Village meeting house, she argued her innocence, proclaiming Tituba and Osborne as the real witches.

When she was found guilty by the judges, including Noyes, according to legend she yelled to him: "I'm no more a witch than you are a wizard, and if you take away my life God will give you blood to drink", although this sentence does not appear in any of contemporary reports of the execution.

In 1710, William Good successfully sued the Great and General Court for health and mental damages done to Sarah and Dorcas, ultimately receiving thirty pounds sterling, one of the largest sums granted to the families of the witchcraft victims.