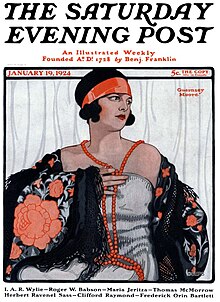

The Saturday Evening Post

From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely circulated and influential magazines among the American middle class, with fiction, non-fiction, cartoons and features that reached two million homes every week.

[7] The Saturday Evening Post published current event articles, editorials, human interest pieces, humor, illustrations, a letter column, poetry with contributions submitted by readers, single-panel gag cartoons, including Hazel by Ted Key, and stories by leading writers of the time.

As a result, the Post published more articles on current events and cut costs by replacing illustrations with photographs for covers and advertisements.

Bryant eventually settled for $300,000 while Butts' case went to the Supreme Court, which held that libel damages may be recoverable (in this instance against a news organization) when the injured party is a non-public official, if the plaintiff can prove that the defendant was guilty of a reckless lack of professional standards when examining allegations for reasonable credibility.

With the magazine still in dire financial straits, Ackerman announced that Curtis would reduce printing costs by cancelling the subscriptions of roughly half of its readers.

[13] Columnist Art Buchwald lampooned the decision, suggesting that "if the Saturday Evening Post considered you a deadbeat, you didn't have much choice but to either pretend you were still getting the magazine and live a lie, or move out of the neighborhood before anyone found out.

[16] In a meeting with employees after the magazine's closure had been announced, Emerson thanked the staff for their professional work and promised "to stay here and see that everyone finds a job".

[17] At a March 1969 post-mortem on the magazine's closing, Emerson stated that The Post "was a damn good vehicle for advertising" with competitive renewal rates and readership reports and expressed what The New York Times called "understandable bitterness" in wishing "that all the one-eyed critics will lose their other eye".

In the magazine, national health surveys are taken to further current research on topics such as cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, ulcerative colitis, spina bifida, and bipolar disorder.

[26] In 1916, Saturday Evening Post editor George Horace Lorimer discovered Norman Rockwell, then an unknown 22-year-old New York City artist.

[citation needed] Another prominent artist was Charles R. Chickering, a freelance illustrator who went on to design numerous postage stamps for the U.S. Post Office.

[28] Cartoonists have included: Irwin Caplan, Clyde Lamb, Jerry Marcus, Frank O'Neal, Charles M. Schulz, and Bill Yates.

[citation needed] The Post published stories and essays by H. E. Bates, Ray Bradbury, Kay Boyle, Agatha Christie, Brian Cleeve, Eleanor Franklin Egan, William Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, C. S. Forester, Ernest Haycox, Robert A. Heinlein, Kurt Vonnegut, Paul Gallico, Normand Poirier, Hammond Innes, Louis L'Amour, Sinclair Lewis, Joseph C. Lincoln, John P. Marquand, Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Roberts Rinehart, Sax Rohmer, William Saroyan, John Steinbeck, Rex Stout, Rob Wagner, Edith Wharton, and P.G.

[citation needed] Poetry published came from poets including: Carl Sandburg, Ogden Nash, Dorothy Parker, and Hannah Kahn.

[29] Emblematic of the Post's fiction was author Clarence Budington Kelland, who first appeared in 1916–17 with stories of homespun heroes, "Efficiency Edgar" and "Scattergood Baines".

[citation needed] For many years William Hazlett Upson contributed a very popular series of short stories about the escapades of Earthworm Tractors salesman Alexander Botts.