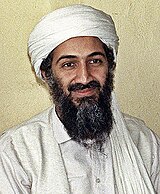

Sayyid Qutb

Even though most of his observations and criticism were leveled at the Muslim world, Qutb also intensely disapproved of the society and culture of the United States,[10][11] which he saw as materialistic, and obsessed with violence and sexual pleasures.

[27] A precocious child, during these years, he began collecting different types of books, including Sherlock Holmes stories, A Thousand and One Nights, and texts on astrology and magic that he would use to help local people with exorcisms (ruqya.

During his early career, Qutb devoted himself to literature as an author and critic, writing such novels as Ashwak (Thorns) and even helped to elevate Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz from obscurity.

He wrote his very first article in the literary magazine al-Balagh in 1922, and his first book, Muhimmat al-Sha’ir fi al-Haya wa Shi’r al-Jil al-Hadir (The Mission of the Poet in Life and the Poetry of the Present Generation), in 1932, when he was 25, in his last year at Dar al-Ulum.

[30] As a literary critic, he was particularly influenced by ‘Abd al-Qahir al-Jurjani (d. 1078), "in his view one of the few mediaeval philologists to have concentrated on meaning and aesthetic value at the expense of form and rhetoric.

Qutb regarded Carrel as a rare sort of Western thinker, one who understood that his civilization "depreciated humanity" by honouring the "machine" over the "spirit and soul" (al-nafs wa al-ruh).

Resigning from the civil service, he joined the Muslim Brotherhood in the early 1950s[43] and became editor-in-chief of the Brothers' weekly Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin, and later head of its propaganda[44][45] section, as well as an appointed member of the working committee and of its guidance council, the highest branch in the organization.

These works represent the final form of Qutb's thought, encompassing his radically anti-secular and anti-Western claims based on his interpretations of the Qur'an, Islamic history, and the social and political problems of Egypt.

One common explanation is that the conditions he witnessed in prison from 1954 to 1964, including the torture and murder of the Muslim Brotherhood members, convinced him that only a government bound by Islamic law could prevent such abuses.

[58] In Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq Qutb argues that anything non-Islamic was evil and corrupt, and that following sharia as a complete system extending into all aspects of life, would bring every kind of benefit to humanity, from personal and social peace, to the "treasures" of the universe.

For example, Qutb's autobiography of his childhood Tifl min al-Qarya (A Child From the Village) makes little mention of Islam or political theory and is typically classified as a secular, literary work.

Late in his life, Qutb synthesized his personal experiences and intellectual development in Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq, a religious and political manifesto for what he believed was a true Islamic system.

[71] Qutb also opposed the then popular ideology of Arab nationalism, having become disillusioned with the 1952 Nasser Revolution after having been exposed to the regime's practices of arbitrary arrest, torture, and deadly violence during his imprisonment.

[72][73]Qutb's intense dislike of the West and ethnic nationalism notwithstanding, a number of authors believe he was influenced by European fascism (Roxanne L. Euben,[74] Aziz Al-Azmeh,[75] Khaled Abou El Fadl).

[Note 4] Qutb's political philosophy has been described as an attempt to instantiate a complex and multilayer eschatological vision, partly grounded in the counter-hegemonic re-articulation of the traditional ideal of Islamic universalism.

"[82]This exposure to abuse of power crucially contributed to the ideas in Qutb's prison-written Islamic manifesto Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq, where he advocated a political system that is the opposite of dictatorship—the Sharia, "God's rule on earth".

[109] In spite of opposition from its moderate factions, the mainstream of Muslim Brotherhood that adheres to Hassan al-Banna's school of thought continues to extoll Qutb as "al-Shahid al-Hayy" (the living martyr).

Despite internal tensions within the group, Qutbist ideologues continue to exert inordinate influence in various echelons of the Muslim Brotherhood and have become a vehicle for popularising Qutb's Jihadist ideas amongst the masses.

Defending Qutb, Ibn Uqla wrote: "Sayyid (may God have mercy upon him) was considered in his era as a science amongst the knowledge of the people who's [sic] curriculum was to fight the oppressors and declare them as disbelievers.

The targeting of Sayyid Qutb (may God have mercy upon him) wasn't just due to his personality ... the goal of his stabbing wasn’t his downfall ... what still worries his enemies and their followers is his curriculum (manhaj) which they fear will spread amongst the children of the Muslims.

"[112]Alongside notable Islamists like Abul A'la Mawdudi, Hasan al-Banna, and Ruhollah Khomeini; Sayyid Qutb is considered one of the most influential Muslim thinkers or activists of the modern era, not only for his ideas but also for what many see as his martyr's death.

Within Egypt itself, the martyrdom of Sayyid Qutb give birth to a new generation of militant Islamists calling for the implementation of sharia; such as Abdus Salam Faraj, 'Umar Abdul Rahman, Shukri Mustafa, etc.

[116] According to authors Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, "it was Sayyid Qutb who fused together the core elements of modern Islamism: the Kharijites' takfir, ibn Taymiyya's fatwas and policy prescriptions, Rashid Rida's Salafism, Maududi's concept of the contemporary jahiliyya and Hassan al-Banna's political activism.

While Qutbist works remain popular amongst the Arab youth and political dissidents; the majority of Sunni Islamists currently view Qutb's proposals as outdated, impractical and prone to extremism.

[130][131] One of Muhammad Qutb's students and later an ardent follower was Ayman Al-Zawahiri, who went on to become a member of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad[132] and later a mentor of Osama bin Laden and the second Emir of Al-Qaeda.

According to Lawrence Wright, who interviewed Azzam, "young Ayman al-Zawahiri heard again and again from his beloved uncle Mahfouz about the purity of Qutb's character and the torment he had endured in prison.

"[137] On the other hand, associate professor of history at Creighton University, John Calvert, states that "the al-Qaeda threat" has "monopolized and distorted our understanding" of Qutb's "real contribution to contemporary Islamism.

Dr. Ali Akbar Alikhani, associate professor at Tehran University, argued that the Qutbist "binary worldview" that divided entire societies into Jahili (ignorant) and Tawhidi (monotheistic), Qutb's allegedly pessimistic view of justice, etc.

Historian Musa Najafi downplayed the role of Qutb's ideas in Iranian revolution and argued that revolutionary symbolism was inherent in Shi'ite scholarly tradition; which was channeled by Khomeini and his followers.

First, he claimed that the world was beset with barbarism, licentiousness, and unbelief (a condition he called jahiliyya, the religious term for the period of ignorance prior to the revelations given to the Prophet Mohammed).