Schizoid personality disorder

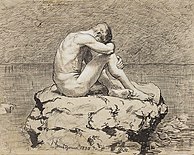

[10] Affected individuals may be unable to form intimate attachments to others and simultaneously possess a rich and elaborate but exclusively internal fantasy world.

[11] Other associated features include stilted speech, a lack of deriving enjoyment from most activities, feeling as though one is an "observer" rather than a participant in life, an inability to tolerate emotional expectations of others, apparent indifference when praised or criticized, being on the asexual spectrum, and idiosyncratic moral or political beliefs.

[28] Some symptoms of SzPD (e.g. solitary lifestyle, emotional detachment, loneliness, and impaired communication), however, have been stated as general risk factors for serious suicidal behavior.

[29][30] The term schizoid was coined in 1908 by Eugen Bleuler to describe a human tendency to direct attention toward one's inner life and away from the external world.

[12] Bleuler describes these personalities as "comfortably dull and at the same time sensitive, people who in a narrow manner pursue vague purposes".

In 1925, Russian psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva described a "schizoid psychopathy" in a group of children, resembling today's SzPD and ASD.

However, various theorist prior to Kretschmer described observable behaviours characteristic of schizoid personality as conceptualized by the early descriptive tradition, including Karl Kahlbaum in 1890, Emil Kraepelin in 1902 and 1919, Bleuler in 1911 and 1920, and Adolf Meyer in 1906, 1908, and 1912.

In addition, Bleuler himself was strongly influenced by earlier dynamic theorists, such as Sigmund Freud on the "day-dreamer" in 1908 and on secondary narcissism in 1914, and Carl Jung on introversion in 1917.

Here, Fairbairn delineated four central schizoid themes: Following Fairbairn's derivation of SzPD from a combination of derealization, depersonalization, splitting, the oral stage of making all subjects into partial objects, and intellectualization;[35] the dynamic psychiatry tradition has continued to produce rich explorations on the schizoid character, most notably from writers Nannarello (1953), Laing (1965), Winnicott (1965),[36] Guntrip (1969), Khan (1974), Akhtar (1987), Seinfeld (1991), Manfield (1992) and Klein (1995).

[38] It was incorporated into the DSM-III as schizoid personality disorder to describe difficulties forming meaningful social relationships and a persistent pattern of disconnection and apathy.

"[48][49] A 2008 study assessing personality and mood disorder prevalence among homeless people at New York City drop-in centers reported an SzPD rate of 65% among this sample.

[90] Professionals may misunderstand the disorder and the client, potentially reinforcing a feeling of failure and negatively impacting their willingness to continue to commit to treatment.

[125][126] Individuals with SzPD can form relationships with others based on intellectual, physical, familial, occupational, or recreational activities, as long as there is no need for emotional intimacy.

Unlike narcissists, schizoid people will often keep their creations private to avoid unwelcome attention or the feeling that their ideas and thoughts are being appropriated by the public.

[156] Aaron Beck and his colleagues report that people with SzPD seem comfortable with their aloof lifestyle and consider themselves observers, rather than participants in the world around them.

But they also mention that many of their schizoid patients recognize themselves as socially deviant (or even defective) when confronted with the different lives of ordinary people – especially when they read books or see movies focusing on relationships.

[161][162][163] Alternatively, there has been an especially large contribution of people with schizoid symptoms to science and theoretical areas of knowledge, including mathematics, physics, economics, etc.

[164] Symptoms of SzPD such as isolation and the blunted affect put people with schizoid personality disorder at a higher risk of suicide and non-suicidal self-harm.

Guntrip (using ideas of Klein, Fairbairn, and Winnicott) classifies these individuals as "secret schizoids", who behave with socially available, interested, engaged, and involved interaction yet remain emotionally withdrawn and sequestered within the safety of the internal world.

He suggests one ask the person what their subjective experience is, to detect the presence of the schizoid refusal of emotional intimacy and preference for objective fact.

[28] A 2013 study looking at personality disorders and Internet use found that being online more hours per day predicted signs of SzPD.

[19] The authors of the 2019 study hypothesized that it is extremely likely that historic cohorts of adults diagnosed with SzPD either also had childhood-onset autistic syndromes or were misdiagnosed.

They stressed that further research to clarify overlap and distinctions between these two syndromes was strongly warranted, especially given that high-functioning autism spectrum disorders are now recognized in around 1% of the population.

They called for the replacement of the SzPD category from future editions of the DSM with a dimensional model which would allow for the description of schizoid traits on an individual basis.

[125][221] If that is true, then many of the more problematic reactions these individuals show in social situations may be partly accounted for by the judgments commonly imposed on people with this style.

Similarly, John Oldham, using a dimensional approach, thinks that most people with schizoid character features do not have a full-blown personality disorder.

He criticizes that this may be due to the current diagnostic criteria: They describe SzPD only by an absence of certain traits, which results in a "deficit syndrome" or "vacuum".

Any schizoid individual may exhibit none or one of the following:[26][225] American psychoanalyst Salman Akhtar provided a comprehensive phenomenological profile of SzPD in which classic and contemporary descriptive views are synthesized with psychoanalytic observations.

This profile is summarized in the table reproduced below that lists clinical features that involve six areas of psychosocial functioning and are organized by "overt" and "covert" manifestations.

However, Akhtar states that his profile has several advantages over the DSM in terms of maintaining historical continuity of the use of the word schizoid, valuing depth and complexity over descriptive oversimplification and helping provide a more meaningful differential diagnosis of SzPD from other personality disorders.