Arnold Schoenberg

[b] They consorted with visual artists, published in Der Blaue Reiter, and wrote atonal, expressionist music, attracting fame and stirring debate.

While working on Die Jakobsleiter (from 1914) and Moses und Aron (from 1923), Schoenberg confronted popular antisemitism by returning to Judaism and substantially developed his twelve-tone technique.

With citizenship (1941) and US entry into World War II, he satirized fascist tyrants in Ode to Napoleon (1942, after Byron), deploying Beethoven's fate motif and the Marseillaise.

In 1933, after long meditation, he returned to Judaism, because he realised that "his racial and religious heritage was inescapable", and to take up an unmistakable position on the side opposing Nazism.

It was during the absence of his wife that he composed "You lean against a silver-willow" (German: Du lehnest wider eine Silberweide), the thirteenth song in the cycle Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten, Op.

The final two movements, again using poetry by George, incorporate a soprano vocal line, breaking with previous string-quartet practice, and daringly weaken the links with traditional tonality.

Wilhelm Bopp [de]), director of the Vienna Conservatory from 1907, wanted a break from the stale environment personified for him by Robert Fuchs and Hermann Graedener.

Writing afterward to Alban Berg, he cited his "aversion to Vienna" as the main reason for his decision, while contemplating that it might have been the wrong one financially, but having made it he felt content.

[14] The deteriorating relation between contemporary composers and the public led him to found the Society for Private Musical Performances (Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen in German) in Vienna in 1918.

He sought to provide a forum in which modern musical compositions could be carefully prepared and rehearsed, and properly performed under conditions protected from the dictates of fashion and pressures of commerce.

[15] Instead, audiences at the Society's concerts heard difficult contemporary compositions by Scriabin, Debussy, Mahler, Webern, Berg, Reger, and other leading figures of early 20th-century music.

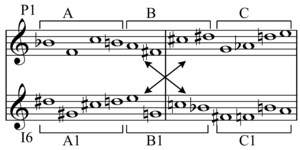

[16] Later, Schoenberg was to develop the most influential version of the dodecaphonic (also known as twelve-tone) method of composition, which in French and English was given the alternative name serialism by René Leibowitz and Humphrey Searle in 1947.

He published a number of books, ranging from his famous Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony) to Fundamentals of Musical Composition,[17] many of which are still in print and used by musicians and developing composers.

Frequent guests included Otto Klemperer (who studied composition privately with Schoenberg beginning in April 1936), Edgard Varèse, Joseph Achron, Louis Gruenberg, Ernst Toch, and, on occasion, well-known actors such as Harpo Marx and Peter Lorre.

[39] After his move to the United States, where he arrived on 31 October 1933,[40] the composer used the alternative spelling of his surname Schoenberg, rather than Schönberg, in what he called "deference to American practice",[41] though according to one writer he first made the change a year earlier.

Beginning with songs and string quartets written around the turn of the century, Schoenberg's concerns as a composer positioned him uniquely among his peers, in that his procedures exhibited characteristics of both Brahms and Wagner, who for most contemporary listeners, were considered polar opposites, representing mutually exclusive directions in the legacy of German music.

3 (1899–1903), for example, exhibit a conservative clarity of tonal organization typical of Brahms and Mahler, reflecting an interest in balanced phrases and an undisturbed hierarchy of key relationships.

The only motivic elements that persist throughout the work are those that are perpetually dissolved, varied, and re-combined, in a technique, identified primarily in Brahms's music, that Schoenberg called "developing variation".

[57][e] "Every smallest turn of phrase, even accompanimental figuration is significant", Berg asserted, parenthetically praising Schoenberg's "excess unheard-of since Bach".

This work is remarkable for its tonal development of whole-tone and quartal harmony, and its initiation of dynamic and unusual ensemble relationships, involving dramatic interruption and unpredictable instrumental allegiances.

However, when it was played again in the Skandalkonzert on 31 March 1913, (which also included works by Berg, Webern and Zemlinsky), "one could hear the shrill sound of door keys among the violent clapping, and in the second gallery the first fight of the evening began."

[68] Schoenberg's serial technique of composition with twelve notes became one of the most central and polemical issues among American and European musicians during the mid- to late-twentieth century.

Beginning in the 1940s and continuing to the present day, composers such as Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono and Milton Babbitt have extended Schoenberg's legacy in increasingly radical directions.

Schoenberg's students have been influential teachers at major American universities: Leonard Stein at USC, UCLA and CalArts; Richard Hoffmann at Oberlin; Patricia Carpenter at Columbia; and Leon Kirchner and Earl Kim at Harvard.

In Europe, the work of Hans Keller, Luigi Rognoni [it], and René Leibowitz has had a measurable influence in spreading Schoenberg's musical legacy outside of Germany and Austria.

[70] In the 1920s, Ernst Krenek criticized a certain unnamed brand of contemporary music (presumably Schoenberg and his disciples) as "the self-gratification of an individual who sits in his studio and invents rules according to which he then writes down his notes".

[76]Ben Earle (2003) found that Schoenberg, while revered by experts and taught to "generations of students" on degree courses, remained unloved by the public.

Despite more than forty years of advocacy and the production of "books devoted to the explanation of this difficult repertory to non-specialist audiences", it would seem that in particular, "British attempts to popularize music of this kind ... can now safely be said to have failed".

[77] In his 2018 biography of Schoenberg's near contemporary and similarly pioneering composer, Debussy, Stephen Walsh takes issue with the idea that it is not possible "for a creative artist to be both radical and popular".

[79] Writer Sean O'Brien comments that "written in the shadow of Hitler, Doktor Faustus observes the rise of Nazism, but its relationship to political history is oblique".