Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

[7] Catherine Allen Latimer, the first African-American librarian hired by the NYPL, was sent to work with Rose as was Roberta Bosely months later.

[9] Together, they created a plan to assist in integrating reading into the lives of the library attendees and cooperated with schools and social organizations in the community.

[15] In late 1924, Rose called a meeting, with attendees including Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, James Weldon Johnson, Hubert Harrison, that decided to focus on preserving rare books, and solicit donations to enhance its African-American collection.

[19] Rose and the National Urban League convinced the Carnegie Foundation to pay $10,000 to Schomburg and then donate the books to the library.

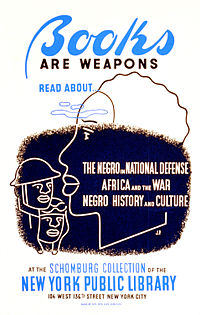

[32] After the outbreak of WWII, Homer started a program of monthly concert recitals in the auditorium to enhance public spirit, but the demand by performers and audience members to continue the practice made it permanent.

[48] Howard Dodson became the director in 1984, at a time when the Schomburg was primarily a cultural center visited by tourists and schoolchildren and its research facilities were known only to scholars.

[49] As early as 1984, the Schomburg was recognized as the most important institution in the world for collections of art and literature of people in Africa or its diaspora.

[52] In March 1987, a public funding campaign was started to raise money to renovate the old library and to enhance the new Center's housing and its functions.

[55] In 2000, the Schomburg Center held an exhibition titled "Lest We Forget: The Triumph Over Slavery", which later went on tour around the world for more than a decade under the sponsorship of UNESCO's Slave Route Project.

His stated goals were for the Schomburg to be a focal point for young adults and to collaborate with the local community, to not only reinforce its pride, but also for the center to be a gateway for revealing the history of Black people worldwide.

On August 1, 2016, the New York Public Library announced that poet and academic Kevin Young would begin as director of the Schomburg in the late fall of 2016.

[60] He is credited with raising more than $10 million in grants and donations, and securing several high-profile acquisitions, including the papers of James Baldwin; Harry Belafonte; and the couple Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee.

[63] Young stepped down at the end of 2020 to assume a new position as director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

[65][66] The next year, the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York provided $8 million for a renovation of the Schomburg Center buildings.

[68][69] In 1998 the Schomburg Collection was considered as consisting of the rarest, and most useful, Afrocentric artifacts of any public library in the United States.

[71] As of 2010, the Collection stood at 10 million objects,[20] The center contains a signed first edition of a book of poems by Phillis Wheatley, archival material of Melville J. Herskovits,[72] John Henrik Clarke,[73] Lorraine Hansberry,[74] Malcolm X and Nat King Cole.

It also includes the papers of Lawrence Brown (1893–1973),[76] Melva L. Price,[77] Ralph Bunche, Léon Damas, William Pickens,[78] Hiram Rhodes Revels, Clarence Cameron White.

It includes musical recordings, black and jazz periodicals, rare books and pamphlets, and tens of thousands of art objects.

[83] The center's collection includes documents signed by Toussaint Louverture and a rare recording of a speech by Marcus Garvey.