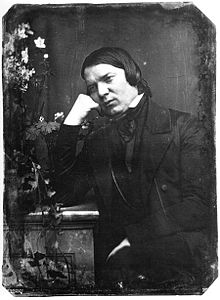

Robert Schumann

Schumann was born in Zwickau, Saxony, to an affluent middle-class family with no musical connections, and was initially unsure whether to pursue a career as a lawyer or to make a living as a pianist-composer.

In his writing for the journal and in his music he distinguished between two contrasting aspects of his personality, dubbing these alter egos "Florestan" for his impetuous self and "Eusebius" for his gentle poetic side.

Schumann and his family moved to Düsseldorf in 1850 in the hope that his appointment as the city's director of music would provide financial security, but his shyness and mental instability made it difficult for him to work with his orchestra and he had to resign after three years.

August, not only a bookseller but also a lexicographer, author, and publisher of chivalric romances, made considerable sums from his German translations of writers such as Cervantes, Walter Scott and Lord Byron.

[6] When he was seven he began studying general music and piano with the local organist, Johann Gottfried Kuntsch, and for a time he also had cello and flute lessons with one of the municipal musicians, Carl Gottlieb Meissner.

[7] Throughout his childhood and youth his love of music and literature ran in tandem, with poems and dramatic works produced alongside small-scale compositions, mainly piano pieces and songs.

[8] He was not a musical child prodigy like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart or Felix Mendelssohn,[4] but his talent as a pianist was evident from an early age: in 1850 the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (Universal Musical Journal) printed a biographical sketch of Schumann which included an account from contemporary sources that even as a boy he possessed a special talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody: From 1820 Schumann attended the Zwickau Lyceum, the local high school of about two hundred boys, where he remained till the age of eighteen, studying a traditional curriculum.

[10] According to the musical historian George Hall, Paul remained Schumann's favourite author and exercised a powerful influence on the composer's creativity with his sensibility and vein of fantasy.

According to his roommate Emil Flechsig [de], he never set foot in a lecture hall,[13] but he himself recorded, "I am industrious and regular, and enjoy my jurisprudence ... and am only now beginning to appreciate its true worth".

[31] The condition had the advantage of exempting him from compulsory military service – he could not fire a rifle[31] – but by 1832 he recognised that a career as a virtuoso pianist was impossible and he shifted his main focus to composition.

[41] According to Chissell, her concerto debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 9 November 1835, with Mendelssohn conducting, "set the seal on all her earlier successes, and there was now no doubting that a great future lay before her as a pianist".

During this period Schumann wrote many piano works, including Kreisleriana (1837), Davidsbündlertänze (1837), Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood, 1838) and Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Prank from Vienna, 1839).

[46] In the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik Schumann wrote enthusiastically about the work and described its "himmlische Länge" – its "heavenly length" – a phrase that has become common currency in later analyses of the symphony.

Hall writes that he had been subject to similar attacks at intervals over a long period, and comments that the condition may have been congenital, affecting August Schumann and Emilie, the composer's sister.

They met the leading figures of the Russian musical scene, including Mikhail Glinka and Anton Rubinstein and were both immensely impressed by Saint Petersburg and Moscow.

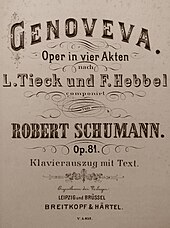

[58] Schumann had been passed over for the conductorship of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in succession to Mendelssohn, and he thought that Dresden, with a thriving opera house, might be the place where he could, as he now wished, become an operatic composer.

In the words of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "A regular if not always approving member of the audience at performances of works by Donizetti, Rossini, Meyerbeer, Halévy and Flotow, he registered his 'desire to write operas' in his travel diary".

In Hall's view, Schumann's diffidence in social situations, allied to mental instability, "ensured that initially warm relations with local musicians gradually deteriorated to the point where his removal became a necessity in 1853".

[72] Hall writes that Brahms proved "a personal tower of strength to Clara during the difficult days ahead": in early 1854 Schumann's health deteriorated drastically.

According to the musicologist Carl Dahlhaus, for Schumann, "music was supposed to turn into a tone poem, to rise above the realm of the trivial, of tonal mechanics, by means of its spirituality and soulfulness".

[90] More recently the later works have been viewed more favourably; Hall suggests that this is because they are now played more often in concert and in recording studios, and have "the beneficial effects of period performance practice as it has come to be applied to mid-19th-century music".

A. Fuller Maitland wrote of the first of these, "Of all the pianoforte works [Carnaval] is perhaps the most popular; its wonderful animation and never-ending variety ensure the production of its full effect, and its great and various difficulties make it the best possible test of a pianist's skill and versatility".

[8] He also wrote some undemanding music with an eye to commercial sales, including the Blumenstück (Flower Piece) and Arabeske (both 1839), which he privately considered "feeble and intended for the ladies".

The first documented public performance of a complete Schumann song cycle was not until 1861, five years after the composer's death; the baritone Julius Stockhausen sang Dichterliebe with Brahms at the piano.

[107][n 10] Conductors including Gustav Mahler, Max Reger, Arturo Toscanini, Otto Klemperer and George Szell have made changes to the instrumentation before conducting his orchestral music.

[134] Based on an episode from Thomas Moore's epic poem Lalla Rookh it reflects the exotic, colourful tales from Persian mythology popular in the nineteenth century.

A complete set was published in 2010 with the songs in chronological order of composition; the pianist Graham Johnson partnered a range of singers including Ian Bostridge, Simon Keenlyside, Felicity Lott, Christopher Maltman, Ann Murray and Christine Schäfer.

[100] Pianists for other recordings of Schumann Lieder have included Gerald Moore, Dalton Baldwin, Erik Werba, Jörg Demus, Geoffrey Parsons, and more recently Roger Vignoles, Irwin Gage and Ulrich Eisenlohr.

Those he influenced included French composers such as Fauré and Messager, who made a joint pilgrimage to his tomb at Bonn in 1879,[150] Bizet, Widor, Debussy and Ravel, along with the developers of symbolism.

They were opposed by the adherents of Liszt and Wagner, including Draeseke, Hans von Bülow (for a time) and in his capacity as a music critic Bernard Shaw, who were in favour of more extreme chromatic harmonies and explicit programmatic content.