Science and technology in Uzbekistan

Science and technology in Uzbekistan examines government efforts to develop a national innovation system and the impact of these policies.

[1] Uzbekistan emerged relatively unscathed from the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, consistently recording economic growth of over 7% from 2007 onwards.

Against a background of strong economic growth, the national development strategy is focusing on nurturing new high-tech industries and orienting the economy towards export markets.

[1] Whereas Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan have been members of the World Trade Organization since 1998, 2013, and 2015 respectively, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have adopted a policy of self-reliance.

[1] Uzbekistan's anti-crisis package for 2009−2012 helped it to weather the financial crisis by injecting funds into strategic economic sectors.

The enterprises established in these FIZ have already produced some inventions and are involved in public−private partnerships through which they co-finance projects in innovation with the Fund for the Reconstruction and Development of Uzbekistan, set up in May 2006.

The ultimate goal of the ongoing legal reform is to harness innovation to solving socio-economic problems and enhancing economic competitiveness.

This draft bill also sets out to create an effective mechanism for the testing, deployment and commercial development of promising scientific work.

The seventh centres on chemical technologies and nanotechnologies and the eighth on Earth sciences, with a focus on geology, geophysics, seismology and raw mineral processing.

State support (financial, material and technical) for innovation is provided directly to specific programmes and projects, rather than to the individual research institutions and hierarchical structures.

Between 2008 and 2014, more than 2 300 contracts for experimental development were signed at these fairs for an investment of more than 85 billion Uzbek soms (UZS), equivalent to US$37 million.

One-quarter (26%) of the proposals vetted concerned biotechnologies, 19% new materials, 16% medicine, 15% oil and gas, 13% energy and metallurgy and 12% chemical technologies.

Prior to the ministry's inception in 2017, the government would fund research projects initiated by the scientific community once per year through a cumbersome procedure.

Now, calls for proposals are announced online every two months and research grants are awarded on a competitive basis, taking into account the needs of the national economy.

The ministry has also increased funding for field expeditions and laboratories for regional universities, in an attempt to diversify research topics and expand the geographical coverage of scientific facilities.

Established by presidential decree in 2018, this fund supports the creation of new research institutes and universities, the registration of patents, short-term scientific trips and schemes to attract foreign scientists.

This is a positive development, since shared use of laboratory infrastructure helps research institutes to spread costs and ensure compliance with international standards, a prerequisite for expanding export markets and increasing protection from low-quality products produced abroad, such as poor-quality drugs.

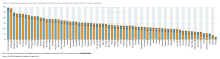

[2] In the region, research spending has hovered around the 0.2–0.3% mark for the past decade but, in 2013, Uzbekistan boosted its own commitment to 0.41% of GDP, distancing Kazakhstan on 0.18%.

Not to be outdone, Kazakhstan has vowed to raise its own research effort to 1% by 2015, according to the State Programme for Accelerated Industrial and Innovative Development.

[1] In order to improve training, the Academy of Sciences created the first cross-sectorial youth laboratories in 2010, in promising fields such as genetics and biotechnology; advanced materials; alternative energy and sustainable energy; modern information technology; drug design; and technology, equipment and product design for the oil and gas and chemical industries.

Even taking population into account, Kazakhstan's output is now much higher than that of its neighbour, with 36 articles per million inhabitants, compared to 11 for Uzbekistan.

[1] In December 2013, Prof. Ibrokhim Abdurakhmonov from the Uzbek Centre of Genomics and Bioinformatics was named ‘researcher of the year’ by the International Cotton Advisory Committee for a ‘gene knockout technology’’ he had developed with biologists from the Texas A&M University (USA) and the US Department of Agriculture’s Office of International Research Programs who had also provided much of the funding.

They are also members of the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC) Programme, which also includes Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, China, Mongolia and Pakistan.

The landlocked Central Asian republics are conscious of the need to co-operate in order to maintain and develop their transport networks and energy, communication and irrigation systems.

Only Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan border the Caspian Sea and none of the republics has direct access to an ocean, complicating the transportation of hydrocarbons, in particular, to world markets.

[1] Uzbekistan is one of the four Central Asian republics that have been involved in a project launched by the European Union in September 2013, IncoNet CA.

The focus of this research projects is on three societal challenges considered as being of mutual interest to both the European Union and Central Asia, namely: climate change, energy and health.

IncoNet CA builds on the experience of earlier projects which involved other regions, such as Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus and the Western Balkans.

It involves a consortium of partner institutions from Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Poland, Portugal, Tajikistan, Turkey and Uzbekistan.