Science policy of the United States

Much of the large-scale policy is made through the legislative budget process of enacting the yearly federal budget, although there are other legislative issues that directly involve science, such as energy policy, climate change, and stem cell research.

Although not the first invention of the United States, this system has a wider spread and stronger influence in the US economy than in other countries.

These agencies are nonpartisan and provide objective reports on topics requested by members of congress.

Of the twelve annual appropriations bills, the most important for R&D are those for Defense; Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (which includes NIH); Commerce, Justice, and Science (which includes NSF, NASA, NIST, and NOAA); and Energy and Water Development.

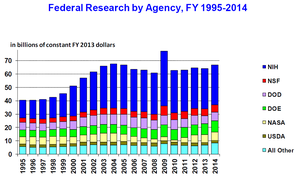

[11] The following chart shows a breakdown for the five agencies with the largest R&D budgets in the Obama administration's FY2015 proposal:[11] Defense R&D has the goal of "maintaining strategic technological advantages over potential foreign adversaries.

[15] The Department of Defense was the third-largest supporter of R&D in academia in FY2012, with only NIH and NSF having larger investments, with DoD the largest federal funder for engineering research and a close second for computer science.

[16] The following chart shows a breakdown for the agencies with the most R&D funding within the Department of Defense in the Obama administration's FY2015 proposal.

The law provides the federal agencies with the broad authority to carry out prize competitions “to stimulate innovation that has the potential to advance the mission of the respective agency.” 15 U.S.C.

Congress set forth the U.S. patent policy in the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980 (codified in 35 U.S. Code § 200 as implemented by 37 CFR part 401).

The policy and objective, as stated in the Bayh-Dole Act, is "to use the patent system to promote the utilization of inventions arising from federally supported research or development,"[22] among others.

[23] Contractors may elect to retain title to any subject invention made in the performance of U.S. government-funded research.

This act will limit or eliminate lengthy legal and bureaucratic challenges that used to accompany contested filings.

However, the pressure to file early may limit the inventor's ability to exploit the period of exclusivity fully.

It may also disadvantage very small entities, for which the legal costs of preparing an application are the main barrier to filing.

Amongst U.S. public opinion, 60% of Americans believe scientific experts should play an active role in policy debates over relevant issues, although this view is divided amongst Democrats and Republicans.

Six states (New Mexico, Maryland, Massachusetts, Washington, California and Michigan) each devoted 3.9% or more of their GDP to R&D in 2010, together contributing 42% of national research expenditure.

In 2010, more than one-quarter of R&D was concentrated in California (28.1%), ahead of Massachusetts (5.7%), New Jersey (5.6%), Washington State (5.5%), Michigan (5.4%), Texas (5.2%), Illinois (4.8%), New York (3.6%) and Pennsylvania (3.5%).

Seven states (Arkansas, Nevada, Oklahoma, Louisiana, South Dakota and Wyoming) devoted less than 0.8% of GDP to R&D.

[2] California is home to Silicon Valley, the name given to the area hosting the leading corporations and start-ups in information technology.

The main biotechnology clusters outside California are the cities of Boston/Cambridge, Massachusetts, Maryland, suburban Washington DC, New York, Seattle, Philadelphia and Chicago.

They shared this distinction with Johnson & Johnson, a multinational based in New Jersey which makes pharmaceutical and healthcare products, as well as medical devices, and were closely followed by automobile giant General Motors (11th), based in Detroit, and pharmaceutical companies Merck (12th) and Pfizer (15th).

Some 7% of the companies on Thomson Reuters' Top 100 Global Innovators list for 2014 are active in biomedical research, equal to the number of businesses in consumer products and telecommunications.

President Eisenhower realized then that if Americans were going to continue to be the world leader in scientific, technological and military advances, the government would need to provide support.

After World War II, the US government began to formally provide support for scientific research and to establish the general structure by which science is conducted in the US.

Senator Kilgore presented a series of bills between 1942–1945 to Congress, the one that most resembles the establishment of the NSF, by name, was in 1944, outlining an independent agency whose main focus was to promote peacetime basic and applied research as well as scientific training and education.

Some specifics outlined were that the director would be appointed and the board would be composed of scientists, technical experts and members of the public.