Merveilleux scientifique

Akin today to science fiction, this literature of scientific imagination revolves around key themes such as mad scientists and their extraordinary inventions, lost worlds, exploration of the solar system, catastrophes and the advent of supermen.

Consequently, in 1909 Renard published a manifesto in which he appropriated a neologism coined in the 19th century, "merveilleux scientifique", adding a hyphen to emphasize the link between the modernization of the fairy tale and the rationalization of the supernatural.

Thus defined, the merveilleux-scientifique novel, set within a rational framework, relies on the alteration of a scientific law around which the plot is built, in order to give the reader food for thought by presenting the threats and delights of science.

[15] This marked a significant departure from their predecessors, who employed the conjectural element as a pretext, following in the footsteps of Savinian Cyrano de Bergerac's utopian, Jonathan Swift's satires, and Camille Flammarion's astronomical exposés.

Marcel Réja, a psychiatrist, discussed this usage in his 1904 article published in "Le Mercure de France" titled "H.-G." It is plausible that Maurice Renard initially came across the term "scientific marvel" in H. G. Wells' works.

"[23] The merveilleux-scientifique novel is fiction whose basis is a sophism; whose object is to lead the reader to a contemplation of the universe closer to the truth; whose means is the application of scientific methods to the comprehensive study of the unknown and the uncertain.In the 19th century, literary critics pondered the future of fantastique stories.

[25] In this article, the author establishes compositional rules for rational novelistic conjecture[26] and introduces the concept of "scientific marvel," previously applied to certain works by writers such as H. G. Wells, J.-H. Rosny aîné, and Jules Verne.

He categorically rejects Jules Verne, accused of contributing to pigeonholing the scientific novel as literature for young people, a publishing sector far removed from the intellectual demands Renard aimed to meet.

[41] After its initial release, critics Edmond Pilon and Henry Durand-Davray [fr] reaffirmed Renard's article, though it was predominantly its reissue two years later as a preface to The Blue Peril that secured its longevity.

[56] Nevertheless, the scientific marvel genre appeared to thrive in 1887, when Rosny aîné published the short novel Les Xipéhuz, which details an encounter between humans and a non-organic intelligence from distant prehistory.

[58] Specifically, his work follows an extensive "war of the kingdoms," from the triumphant emergence of our species in prehistoric times to the eventual replacement of Homo sapiens by another life form that dominates the Earth's surface in the distant future.

[59] Thus, in Les Xipéhuz, Rosny aîné presents a confrontation between primitive humanity and an unfamiliar race, and in La Force mystérieuse [fr] (1913), he envisions a modern cataclysm that intensifies, compelling humankind to implement social reorganization.

[79] For instance, Maurice Leblanc recounts in Les Trois Yeux [fr] (1919) the experience of a scientist who develops a B-ray-treated coating allowing past images to appear on a wall, as during a cinematograph session.

For instance, Maurice Renard's L'Homme au corps subtil [fr] (1913) depicts the ability of Professor Bouvancourt to traverse matter using the penetrating power of X-rays on the human body, echoing François Dutilleul's capabilities from Marcel Aymé's Le Passe-Muraille (1941).

Conversely, in "Une invasion de macrobes [fr]" (1909),[83] André Couvreur portrays the opposite process, where the malevolent scientist Tornada causes a tremendous increase in microbe size.

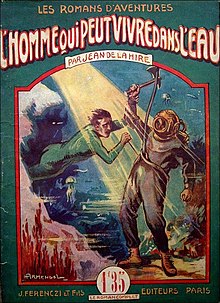

[96] Similarly, in Lucifer (novel) [fr], Jean de La Hire depicts Baron Glô van Warteck, a villainous mastermind who has created a tool that boosts his psychic abilities.

For instance, in Aigle et colombe, novelist René d'Anjou portrays the alchemist Fédor Romalewski developing various inventions based on scientific discoveries, including super-radium, X-rays, and Z-rays.

[100] The vanishing of certain materials is a recurring motif in conjectural literature,[101] exemplified by the loss of metal in Gaston de Pawlowski's[102] Les Ferropucerons (1912)[nb 9] and Serge-Simon Held's[103] La Mort du fer (1931).

[108] Similarly, in Rosny aîné's short story Un autre monde (nouvelle) [fr] (1895), the narrator Gueldrois employs his augmented vision to detect invisible geometric life forms prevalent in our surroundings.

Ben Jackson's[nb 10] novel, L' ge Alpha ou la marche du temps (1942), takes place in a city of the 21st century characterized by high levels of inequality and widespread use of atomic energy.

General interest magazines also published a variety of serialized novels, including Lectures pour tous, which contained short stories from various authors such as Octave Béliard, Maurice Renard, Raoul Bigot, Noëlle Roger, and J.-H. Rosny aîné.

[14] Smaller publishers participated in this movement as well, including Editions La Fenêtre ouverte, where writer and translator Régis Messac debuted the "Les Hypermondes [fr]" collection in 1935.

French novelists of merveilleux scientifique coexist alongside acclaimed authors including Scotland's Conan Doyle, England's Henry Rider Haggard, Ireland's Sheridan Le Fanu, and Australia's Carlton Dawe.

Playwright André de Lorde utilized this inspiration to develop his horror performances centering on perilous mental patients, presented at the Théâtre du Grand-Guignol during the early 20th century and beyond.

[153] Additionally, employing this French literary figure serves to reinforce the legitimacy of the genre while supporting a marketing campaign to increase sales of the Hetzel collection, which has been owned by Hachette since July 1914.

[164] In 1950, Jean-Jacques Bridenne published La Littérature française d'imagination scientifique, sharing pioneering research on novels resulting from late 19th century[164] scientific discoveries and providing insights into the genre.

Therefore, the revised text is L' ge d'or de la science-fiction française (The Golden Age of French Science Fiction), in which he undertakes an initial reflection on this literature of scientific imagination.

A number of specialized websites, such as Philippe Ethuin's Archeosf and Jean-Luc Boutel's Sur l'autre face du monde, are also part of this rediscovery movement, taking stock of and critiquing these early works.

[180] This resurgence could either be in response to the dominance of Anglo-Saxon science fiction or simply a yearning for a more innocent form of the genre,[181] and although the books were still catered to a niche audience, they were published on a much bigger scale.

[192] If the label "scientific marvel" no longer appears in literature, the foundation of the genre remains intact: the encounter between a human and an extraordinary element, be it an object, a creature, or a physical phenomenon.