Sclaveni

Their weapons were javelins, spears, bows nocked with poison tipped arrows and sturdy wooden shields, but body armour was rare.

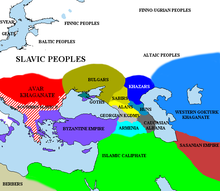

[5] The first Slavic raid south of the Danube was recorded by Procopius (writing in the mid-6th century CE), who mentions an attack of the Antes, "who dwell close to the Sclaveni", probably in 518.

[13] In the summer of 550, the Sclaveni came close to Naissus, and were seen as a great threat, however, their intent of capturing Thessaloniki and the surroundings was thwarted by Germanus.

John of Ephesus noted in 581: "the accursed people of the Slavs set out and plundered all of Greece, the regions surrounding Thessalonica, and Thrace, taking many towns and castles, laying waste, burning, pillaging, and seizing the whole country."

According to Florin Curta, John exaggerated the intensity of the Slavic incursions since he was influenced by his confinement in Constantinople from 571 up until 579,[22] moreover, he perceived the Slavs as God's instrument for punishing the persecutors of the Monophysites.

The final attempt to restore the Romans' northern border occurred between 591 and 605, when the end of conflicts with Persia allowed Emperor Maurice to transfer units to the north.

[27] During the same year of the siege, the Slavs used their monoxyla in order to transport the 3,000 troops of the allied Sassanids across the Bosphorus which the latter had promised the khagan of the Avars.

[28] Based on the De Administrando Imperio, it is also theorized that the migration of White Croats and Serbs could have been part of a second Slavic wave during Heraclius' reign.

[35] In 681, the Byzantines were compelled to sign a humiliating peace treaty, forcing them to acknowledge Bulgaria as an independent state, to cede the territories to the north of the Balkan Mountains and to pay an annual tribute.

The Slavs were allowed to retain their chiefs, to abide to their customs and in return they were to pay tribute in kind and to provide foot soldiers for the army.

[40] The Seven Slavic tribes were relocated to the west to protect the frontier with the Avar Khaganate, while the Severi were resettled in the eastern Balkan Mountains to guard the passes to the Byzantine Empire.

Vasil Zlatarski and John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. suggest that they were not particularly numerous, numbering some 10,000,[41][42] while Steven Runciman considers that the tribe must have been of considerable dimensions.

According to later sources such as the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, the Drougoubitai, Sagoudatai, Belegezitai, Baiounetai, and Berzetai laid siege to Thessaloniki in 614–616.

Slavic pressure on Thessaloniki ebbed after 617/618, until the Siege of Thessalonica (676–678) by a coalition of Rynchinoi, Sagoudatai, Drougoubitai and Stroumanoi attacked.

It seems that the Slavs settled on places of earlier settlements and probably merged later with the local populations of Greek descent to form mixed Byzantine-Slavic communities.

For example, the Byzantinist Peter Charanis believes the Chronicle of Monemvasia to be a reliable account, but other scholars point out that it greatly overstates the impact of the Slavic and Avar raids of Greece during this time.

[58] Max Vasmer, a prominent linguist and Indo-Europeanist, complements late medieval historical accounts by listing 429 Slavic toponyms from the Peloponnese alone.

[56] Some villages were probably mixed, and quite possibly, some degree of Hellenization of the Slavs by the Greeks of the Peloponnese had already begun during this period, before re-Hellenization was completed by the Byzantine emperors.

That was achieved through its theme system, which refers to an administrative province on which an army corps was centred under the control of a strategos ("general").

[63] Subduing the Slavs in the themes was simply a matter of accommodating the needs of the Slavic elites and providing them with incentives for their inclusion into the imperial administration.

[65] According to the Chronicle of Monemvasia the Byzantine governor of Corinth went in 805 to war with the Slavs, obliterated them and allowed the original inhabitants to claim their own.

[67] By the late 9th century, most of Greece was culturally and administratively Greek again except for a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains such as the Melingoi and Ezeritai.

[70] In return, many Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor were brought to the interior of Greece to increase the number of defenders at the Emperor's disposal and to dilute the concentration of Slavs.

[64] As more of the peripheral territories of the Byzantine Empire were lost in the following centuries, such as Sicily, southern Italy and Asia Minor, their Greek-speakers made their own way back to Greece.

The re-Hellenization of Greece by population transfers and cultural activities of the Church was successful, which suggests that Slavs found themselves in the midst of many Greeks.

As the Slavs supposedly occupied the entire Balkan interior, Constantinople was effectively cut off from the Dalmatian city-states under its (nominal) control.

[72] Thus, Dalmatia came to have closer ties with the Italian Peninsula because of its ability to maintain contact by sea, but it too was troubled by Slavic pirates.

[72] Additionally, Constantinople was cut off from Rome, which contributed to the growing cultural and political separation between the two centres of European Christendom.