Scopes trial

William Jennings Bryan, three-time presidential candidate and former secretary of state, argued for the prosecution, while Clarence Darrow served as the defense attorney for Scopes.

The trial publicized the fundamentalist–modernist controversy, which set modernists, who said evolution could be consistent with religion,[4] against fundamentalists, who said the word of God as revealed in the Bible took priority over all human knowledge.

[6] William Jennings Bryan thanked Peay enthusiastically for the bill: "The Christian parents of the state owe you a debt of gratitude for saving their children from the poisonous influence of an unproven hypothesis.

"[7] In response, the American Civil Liberties Union financed a test case in which John Scopes, a Tennessee high school science teacher, agreed to be tried for violating the Act.

The two sides brought in the biggest legal names in the nation, Bryan for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for the defense, and the trial was followed on radio transmissions throughout the United States.

[17][18] The original prosecutors were Herbert E. and Sue K. Hicks, two brothers who were local attorneys and friends of Scopes, but the prosecution was ultimately led by Tom Stewart, a graduate of Cumberland School of Law, who later became a U.S.

Stewart was aided by Dayton attorney Gordon McKenzie, who supported the anti-evolution bill on religious grounds, and described evolution as "detrimental to our morality" and an assault on "the very citadel of our Christian religion.

As Scopes pointed out to James Presley in the book Center of the Storm, on which the two collaborated: "After [Bryan] was accepted by the state as a special prosecutor in the case, there was never any hope of containing the controversy within the bounds of constitutionality.

[26] The prosecution team was led by Tom Stewart, district attorney for the 18th Circuit (and future United States Senator), and included, in addition to Herbert and Sue Hicks, Ben B. McKenzie and William Jennings Bryan.

In his conclusion, Darrow declared that Bryan's "duel to the death" against evolution should not be made one-sided by a court ruling that took away the chief witnesses for the defense.

[36] On the seventh day of the trial, Clarence Darrow took the unorthodox step of calling William Jennings Bryan, counsel for the prosecution, to the stand as a witness in an effort to demonstrate that belief in the historicity of the Bible and its many accounts of miracles was unreasonable.

The scientists the defense had brought to Dayton—and Charles Francis Potter, a modernist minister who had engaged in a series of public debates on evolution with the fundamentalist preacher John Roach Straton—prepared topics and questions for Darrow to address to Bryan on the witness stand.

[45] After the defense's final attempt to present evidence was denied, Darrow asked the judge to bring in the jury only to have them come to a guilty verdict: We claim that the defendant is not guilty, but as the court has excluded any testimony, except as to the one issue as to whether he taught that man descended from a lower order of animals, and we cannot contradict that testimony, there is no logical thing to come except that the jury find a verdict that we may carry to the higher court, purely as a matter of proper procedure.

Under Tennessee law, when the defense waived its right to make a closing speech, the prosecution was also barred from summing up its case, preventing Bryan from presenting his prepared summation.

[51] Writing for the court two sittings and one year after receiving the appeal,[52] Chief Justice Grafton Green rejected this argument, holding that the Tennessee Religious Preference clause was designed to prevent the establishment of a state religion as had been the experience in England and Scotland at the writing of the Constitution, and held: We are not able to see how the prohibition of teaching the theory that man has descended from a lower order of animals gives preference to any religious establishment or mode of worship.

Since this cause has been pending in this court, we have been favored, in addition to briefs of counsel and various amici curiae, with a multitude of resolutions, addresses, and communications from scientific bodies, religious factions, and individuals giving us the benefit of their views upon the theory of evolution.

Such a course is suggested to the Attorney General.Attorney General L. D. Smith immediately announced that he would not seek a retrial, while Scopes' lawyers offered angry comments on the stunning decision.

[53] In 1968, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas 393 U.S. 97 (1968) that such bans contravene the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because their primary purpose is religious.

Bryan, unlike the other leaders, brought name recognition, respectability, and the ability to forge a broad-based coalition of fundamentalist and mainline religious groups which argued in defense of the anti-evolutionist position.

[57] The trial escalated the political and legal conflict in which strict creationists and scientists struggled over the teaching of evolution in Arizona and California science classes.

They sought to ban evolution as a topic for study in the schools or, failing that, to relegate it to the status of unproven hypothesis perhaps taught alongside the biblical version of creation.

This struggle occurred later in the Southwest than elsewhere, finally collapsing in the Sputnik era after 1957, when the national mood inspired increased trust for science in general and for evolution in particular.

[75] The media's portrayal of Darrow's cross-examination of Bryan, and the play and movie Inherit the Wind (1960), caused millions of Americans to ridicule religious-based opposition to the theory of evolution.

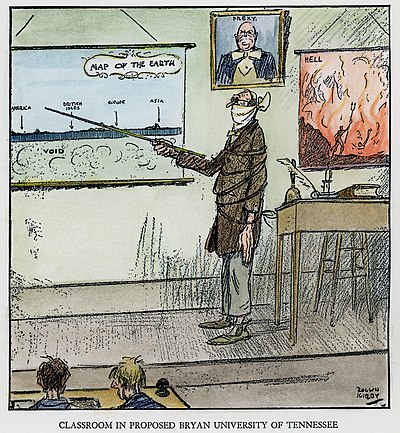

[79] Anticipating that Scopes would be found guilty, the press fitted the defendant for martyrdom and created an onslaught of ridicule, and hosts of cartoonists added their own portrayals to the attack.

For example: Overwhelmingly, the butt of these jokes was the prosecution and those aligned with it: Bryan, the city of Dayton, the state of Tennessee, and the entire South, as well as fundamentalist Christians and anti-evolutionists.

Rare exceptions were found in the Southern press, where the fact that Darrow had saved Leopold and Loeb from the death penalty continued to be a source of ugly humor.

"[85] Attacks on Bryan were frequent and acidic: Life awarded him its "Brass Medal of the Fourth Class" for having "successfully demonstrated by the alchemy of ignorance hot air may be transmuted into gold, and that the Bible is infallibly inspired except where it differs with him on the question of wine, women, and wealth".

[86] Vituperative attacks came from journalist H. L. Mencken, whose syndicated columns from Dayton for The Baltimore Sun drew vivid caricatures of the "backward" local populace, referring to the people of Rhea County as "Babbits", "morons", "peasants", "hill-billies", "yaps", and "yokels".

I expected to find a squalid Southern village, with darkies snoozing on the horse-blocks, pigs rooting under the houses and the inhabitants full of hookworm and malaria.

[93] After Raulston ruled against the admission of scientific testimony, Mencken left Dayton, declaring in his last dispatch "All that remains of the great cause of the State of Tennessee against the infidel Scopes is the formal business of bumping off the defendant.