Royal Scots Greys

[11] Scotland grew increasingly restive in the period before the November 1688 Glorious Revolution and the regiment was employed in an ultimately vain attempt to stem the tide of rebellion.

[18] Following the 1707 Acts of Union, the English and Scottish military establishments were merged, causing debates over regimental precedence; this was connected to the price of commissions, seniority and pay.

[3] The Scots Greys continue to pursue the shattered left wing of the Jacobite force as it fled for nearly two miles until it was blocked by the river Allan.

[22] An attempt by the Allies to relieve Tournai led to the May 1745 Battle of Fontenoy; this featured a series of bloody frontal assaults by the infantry and the cavalry played little part, with the exception of covering the retreat.

[23] When the 1745 Rising began in July many British units were recalled to Scotland but the regiment remained in Flanders, fighting at the Battle of Rocoux on 11 October 1746, a French tactical victory.

[24] The French won another tactical victory at Lauffeld on 2 July, where the Scots Greys took part in Ligonier's charge, one of the best known cavalry actions in British military history.

[40] Four troops of the Scots Greys were alerted for possible foreign deployment in 1792 and were transported to the continent in 1793 to join the Duke of York's army operating in the low countries.

[42] Despite their exploits in the low countries, and the fact that Britain would be heavily engaged around the globe fighting Revolutionary and, later, Napoleonic France, the Scots Greys would not see action until 1815.

[49] As the rest of the British heavy cavalry advanced against the French infantry, just after 1:30 pm, Lieutenant-Colonel Hamilton witnessed Pack's brigade beginning to crumble, and the 92nd Highlanders falling back in disorder.

As Captain Duthilt, who was present with de Marcognet's 3rd Division, wrote of the Scots Greys charge: Just as I was pushing one of our men back into the ranks I saw him fall at my feet from a sabre slash.

This is what happened, in vain our poor fellows stood up and stretched out their arms; they could not reach far enough to bayonet these cavalrymen mounted on powerful horses, and the few shots fired in chaotic melee were just as fatal to our own men as to the English.

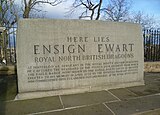

[51] As the Scots Greys waded through the French column, Sergeant Charles Ewart found himself within sight of the eagle of 45e Régiment de Ligne (45th Regiment of the Line).

[55] Unlike the disordered column that had been engaged in attacking Pack's brigade, some of Durutte's men had time to form square to receive the cavalry charge.

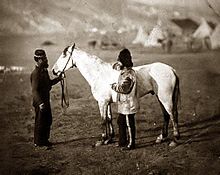

Assigned to Brigadier-General Sir James Scarlett's Heavy Brigade of the Cavalry Division, the Scots Greys, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Griffith arrived in the Crimea in 1854.

Although Scarlett had spent precious minutes ordering his line, it soon proved to be unwieldy, especially in the sector occupied by the Scots Greys, who had to pick their way through the abandoned camp of the Light Brigade.

Seeing that the Scots Greys were again cut off, the Royal Dragoons, finally arriving to the fight after disobeying Scarlett's order to remain with the Light Brigade, charged to their assistance, helping to push the Russians back.

[75] Amid the hacking and slashing of the sabre battle, the Russian cavalry had had enough, and retreated back up the hill, pursued for a short time by the Scots Greys and the rest of the regiments.

Two members of the Scots Greys, Regimental Sergeant Major John Grieve and Private Henry Ramage, were among the first to be awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions on 25 October.

[78] By 1857, the regiment was back in Britain, returning to its peacetime duties in England, Scotland and Ireland for the next fifty years of service without a shot being heard in anger.

The largest detachment of the Scots Greys to see action were the two officers and 44 men who were sent to join the Heavy Camel Regiment during the expedition to relieve Gordon at Khartoum.

As word spread through the camp, the British prisoners over-powered the guards, mostly men either too old or too young to be out on commando, pushed their way out of confinement to meet with the Scots Greys.

[95] In the aftermath of the Battle of Le Cateau, the Scots Greys, with the rest of the 5th Cavalry Brigade, helped to temporarily check the German pursuit at Cerizy, on 28 August 1914.

[95] After being pulled from the trenches at the Aisne, the Scots Greys were sent north to Belgium as part of the lead elements as the British and Germans raced towards the sea, each trying to outflank the other.

Although the German blitzkrieg attacks in Poland, France and the Low Countries demonstrated that the tank was now the dominant weapon, the Scots Greys continued to be equipped with horses.

Charging forward as if still mounted on horses, the Scots Greys captured eleven artillery pieces and approximately 300 prisoners in exchange for one Stuart put out of action.

Leading the 4th Armour Brigade's advance, the Scots Greys entered the village, over-running the infantry defenders, capturing 250 men of the 115 Panzergrenadier Regiment.

[121] Finally, on 16 September, the Scots Greys were committed to the fight as a regiment, helping to stop, and then drive back, the Twenty-Sixth Panzer Division, allowing X Corps to advance out of the beachhead.

The regiment also helped to capture the Wilhelmina Canal and clear German resistance along the Lower Rhine to secure the allied flank for the eventual drive into Germany.

As part of the reductions started by the 1957 Defence White Paper, the Royal Scots Greys were scheduled to be amalgamated with the 3rd Carabiniers (Prince of Wales's Dragoon Guards).

[141] Up until at least the Second World War, The Greys also had a popular, if somewhat derogatory, nickname of "The Bird Catchers", derived from their cap badge and the capture of the Eagle at Waterloo.