Scott Joplin

Biographer Susan Curtis speculates that Florence's support of her son's musical education was a critical factor behind her separation from Giles, who wanted the boy to pursue practical employment that would supplement the family income.

[18] Weiss, as described by San Diego Jewish World writer Eric George Tauber, "was no stranger to [receiving] race hatred ... As a Jew in Germany, he was often slapped and called a 'Christ-killer.

[18] In the late 1880s, having performed at various local events as a teenager, Joplin gave up his job as a railroad laborer and left Texarkana to become a traveling musician.

[32] Joplin's visit to Temple, Texas, enabled him to have three pieces published there in 1896, including the "Great Crush Collision March", which commemorated a planned train crash on the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad on September 15 that he may have witnessed.

"[33] While in Sedalia, Joplin taught piano to students who included future ragtime composers Arthur Marshall, Brun Campbell and Scott Hayden.

[3] Joplin's first biographer, Rudi Blesh, wrote that during its first six months the piece sold 75,000 copies and became "the first great instrumental sheet music hit in America.

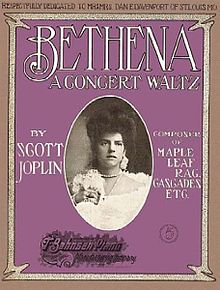

[44] "Bethena", Joplin's first work copyrighted after Freddie's death, was described by one biographer as "an enchantingly beautiful piece that is among the greatest of ragtime waltzes".

Poorly staged and with only Joplin on piano accompaniment, it was "a miserable failure" to a public not ready for "crude" black musical forms—so different from the European grand opera of that time.

[49] Biographer Vera Brodsky Lawrence speculates that Joplin was aware of his advancing deterioration due to syphilis and was "consciously racing against time."

His grave, located at St. Michael's Cemetery in East Elmhurst was finally given a marker in 1974, the year The Sting, which showcased his music, won Best Picture at the Oscars.

[16] When Joplin was learning the piano, serious musical circles condemned ragtime because of its association with the vulgar and inane songs "cranked out by the tune-smiths of Tin Pan Alley.

[57] This new art form, the classic rag, combined Afro-American folk music's syncopation and 19th-century European romanticism, with its harmonic schemes and its march-like tempos.

[34] Joplin wrote his rags as "classical" music in miniature form in order to raise ragtime above its "cheap bordello" origins and produced work that opera historian Elise Kirk described as "more tuneful, contrapuntal, infectious, and harmonically colorful than any others of his era.

In addition, the themes of superstition and mysticism evident in Treemonisha are common in the operatic tradition, and certain aspects of the plot echo devices in the work of the German composer Richard Wagner (of which Joplin was aware).

In addition, African-American folk tales also influence the story—the wasp nest incident is similar to the story of Br'er Rabbit and the briar patch.

"[71] Curtis's conclusion is similar: "In the end, Treemonisha offered a celebration of literacy, learning, hard work, and community solidarity as the best formula for advancing the race.

[72] As Rick Benjamin, the founder and director of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra, found out, Joplin succeeded in performing Treemonisha for paying audiences in Bayonne, New Jersey, in 1913.

[73] Joplin's skills as a pianist were described in glowing terms by a Sedalia newspaper in 1898, and fellow ragtime composers Arthur Marshall and Joe Jordan both said that he played the instrument well.

[77] Berlin theorizes that by the time Joplin reached St. Louis, he may have experienced discoordination of the fingers, tremors, and an inability to speak clearly—all symptoms of the syphilis that killed him in 1917.

[78] Biographer Blesh described the second roll recording of "Maple Leaf Rag" on the UniRecord label from June 1916 as "shocking...disorganized and completely distressing to hear.

"[34] Joshua Rifkin, a leading Joplin recording artist, wrote, "A pervasive sense of lyricism infuses his work, and even at his most high-spirited, he cannot repress a hint of melancholy or adversity...He had little in common with the fast and flashy school of ragtime that grew up after him.

[85] Composer and actor Max Morath found it striking that the vast majority of Joplin's work did not enjoy the popularity of the "Maple Leaf Rag", because while the compositions were of increasing lyrical beauty and delicate syncopation, they remained obscure and unheralded during his life.

Audiophile Records released a two-record set, The Complete Piano Works of Scott Joplin, The Greatest of Ragtime Composers, performed by Knocky Parker, in 1970.

"[95] In January 1971, Harold C. Schonberg, music critic at The New York Times, having just heard the Rifkin album, wrote a featured Sunday edition article titled "Scholars, Get Busy on Scott Joplin!

[100] His version of "The Entertainer" reached number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the American Top 40 music chart on May 18, 1974,[101][102] prompting The New York Times to write, "The whole nation has begun to take notice.

"[99] On October 22, 1971, excerpts from Treemonisha were presented in concert form at Lincoln Center, with musical performances by Bolcom, Rifkin and Mary Lou Williams supporting a group of singers.

[107] That year also brought the premiere by the Los Angeles Ballet of Red Back Book, choreographed by John Clifford to Joplin rags from the collection of the same name, including both solo piano performances and arrangements for full orchestra.

The home Joplin rented in St. Louis from 1900 to 1903 was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1976 and was saved from destruction by the local African American community.

A newer heritage project has expanded coverage to include the more complex social history of black urban migration and the transformation of a multi-ethnic neighborhood to the contemporary community.

Part of this diverse narrative now includes coverage of uncomfortable topics of racial oppression, poverty, sanitation, prostitution, and sexually transmitted diseases.