Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), 1902–1904, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh.

Although overshadowed in terms of prestige by Robert Falcon Scott's concurrent Discovery Expedition, the SNAE completed a full programme of exploration and scientific work.

"[1] Despite this, Bruce received no formal honour or recognition from the British Government, and the expedition's members were denied the prestigious Polar Medal despite vigorous lobbying.

His focus on serious scientific exploration was out of fashion with his times, and his achievements, unlike those of the polar adventurers Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen, soon faded from public awareness.

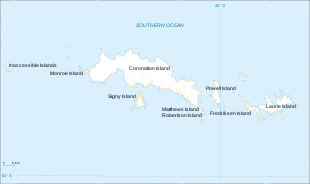

The SNAE's permanent memorial is the Orcadas weather station, which was set up in 1903 as "Omond House" on Laurie Island, South Orkneys, and has been in continuous operation ever since.

During his student years – the 1880s and early 1890s – William Speirs Bruce built up his knowledge of the natural sciences and oceanography, by studying at summer courses under distinguished tutors such as Patrick Geddes and John Arthur Thomson.

Rudmose Brown records that of the original eight dogs, four survived the expedition; they "pulled well in harness, their only weak point being their paws which... were apt to be cut when on rough ice".

On her way southward she called at the Irish port of Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire),[C] at Funchal in Madeira, and then the Cape Verde Isles[18] before an unsuccessful attempt was made to land at the tiny, isolated equatorial archipelago known as St Paul's Rocks.

This attempt almost cost the life of the expedition's geologist and medical officer, James Harvie Pirie, who was fortunate to escape from the shark-infested seas after misjudging his leap ashore.

After several foiled attempts to locate a suitable anchorage, and with its rudder seriously damaged by ice, the ship finally found a sheltered bay on the southern shore of Laurie Island, the most easterly of the South Orkneys chain.

[26] Bruce instituted a comprehensive programme of work, involving meteorological readings, trawling for marine samples, botanical excursions, and the collection of biological and geological specimens.

The 20-by-20-foot (6 by 6 m) building – its walls built from local materials using the dry stone method, and roof improvised from wood and canvas sheeting – had two windows and was fitted for six people.

Near Omond House, a wooden hut was constructed for magnetic observations and a cairn was built, 9 ft (2.7 m) high, on top of which the Union Flag and the Saltire were displayed.

[30] Scotia was made seaworthy again, but remained icebound throughout September and October; it was not until 23 November that strong winds broke up the bay ice, allowing her to float free.

Bruce had further business in the city; he intended to persuade the Argentine government to assume responsibility for the Laurie Island meteorological station after the expedition's departure.

[31] During the voyage to Buenos Aires, Scotia ran aground in the Río de la Plata estuary, and was stranded for several days before floating free and being assisted into port by a tug, on 24 December.

[31] On 20 January 1904, Bruce confirmed an agreement whereby three scientific assistants of the Argentine government would travel back to Laurie Island to work for a year, under Robert Mossman, as the first stage of an annual arrangement.

A week later, having settled the meteorological party, who were to be relieved a year later by the Argentine gunboat Uruguay, Scotia set sail for her second voyage to the Weddell Sea.

[38] Throughout this part of the voyage a regular programme of depth soundings, trawls, and sea-bottom samples provided a comprehensive record of the oceanography and marine life of the Weddell Sea.

[44][45] A formal reception for 400 people was held at the Marine Biological Station, Millport, at which John Murray read a telegram of congratulation from King Edward VII.

[46] Following the expedition, more than 1,100 species of animal life, 212 of them previously unknown to science, were catalogued;[47] there was no official acknowledgement from London, where under the influence of Markham the work of the SNAE tended to be ignored or denigrated.

[49][E] Some of the aversion of the London geographical establishment may have arisen from Bruce's overt Scottish nationalism, reflected in his own prefatory note to Rudmose Brown's expedition history, in which he said: "While Science was the talisman of the Expedition, Scotland was emblazoned on its flag; and it may be that, in endeavouring to serve humanity by adding another link to the golden chain of science, we have also shown that the nationality of Scotland is a power that must be reckoned with".

[50] A significant consequence of the expedition was the establishment by Bruce, in Edinburgh, of the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory, which was formally opened by Prince Albert of Monaco in 1906.

[51] The Laboratory served as a repository for the large collection of biological, zoological and geological specimens amassed during the Scotia voyages, and also during Bruce's earlier Arctic and Antarctic travels.

[51] Although Bruce continued to visit the Arctic for scientific and commercial purposes, he never led another Antarctic expedition, his plans for a transcontinental crossing being stifled through lack of funding.

[51] A proposal to convert the Laboratory into a permanent Scottish National Oceanographic Institute failed to come to fruition and, because of difficulties with funding, Bruce was forced to close it down in 1919.

[F] Bruce lacked charisma, had no public relations skills ("...as prickly as the Scottish thistle itself", according to a lifelong friend[1]), and tended to make powerful enemies.

[54] One hundred years after Bruce, a 2003 expedition, in a modern version of Scotia, used information collected by the SNAE as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia during the past century.