Scottish folk music

After the Reformation, the secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the Kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings.

The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmons, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch.

This was changed by individuals including Alan Lomax, Hamish Henderson and Peter Kennedy, through collecting, publications, recordings and radio programmes.

There was also a strand of popular Scottish music that benefited from the arrival of radio and television, which relied on images of Scottishness derived from tartanry and stereotypes employed in music hall and variety, exemplified by the TV programme The White Heather Club which ran from 1958 to 1967, hosted by Andy Stewart and starring Moira Anderson and Kenneth McKeller.

Melodies have survived separately in the post-Reformation publication of The Gude and Godlie Ballatis (1567),[1] which were spiritual satires on popular songs, adapted and published by the brothers James, John and Robert Wedderburn.

[1] After the Reformation, the secular popular tradition of music continued, despite attempts by the Kirk, particularly in the Lowlands, to suppress dancing and events like penny weddings at which tunes were played.

This period saw the creation of the ceòl mór (the great music) of the bagpipe, which reflected its martial origins, with battle-tunes, marches, gatherings, salutes and laments.

[4] The Highlands in the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch.

[3] This tradition continued into the nineteenth century, with major figures such as the fiddlers Niel (1727–1807) and his son Nathaniel Gow (1763–1831), who, along with a large number of anonymous musicians, composed hundreds of fiddle tunes and variations.

[8] They remained an oral tradition until increased interest in folk songs in the eighteenth century led collectors such as Bishop Thomas Percy to publish volumes of popular ballads.

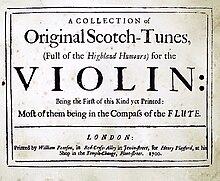

[8] In Scotland the earliest printed collection of secular music was by publisher John Forbes, produced in Aberdeen in 1662 as Songs and Fancies: to Thre, Foure, or Five Partes, both Apt for Voices and Viols.

[13] The tradition continued with figures including James Scott Skinner (1843–1927), known as the "Strathspey King", who played the fiddle in venues ranging from the local functions in his native Banchory, to urban centres of the south and at Balmoral.

Major composers included Alexander Mackenzie (1847–1935), William Wallace (1860–1940), Learmont Drysdale (1866–1909), Hamish MacCunn (1868–1916) and John McEwen (1868–1948).

[18] MacCunn's overture The Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887), his Six Scotch Dances (1896), his operas Jeanie Deans (1894) and Dairmid (1897) and choral works on Scottish subjects[15] have been described by I. G. C. Hutchison as the musical equivalent of the Scots Baronial castles of Abbotsford and Balmoral.

[19] Similarly, McEwen's Pibroch (1889), Border Ballads (1908) and Solway Symphony (1911) incorporated traditional Scottish folk melodies.

[20] After World War II, traditional music in Scotland was marginalised, but, unlike in England, it remained a much stronger force, with the Céilidh house still present in rural communities until the early 1950s and traditional material still performed by the older generation, even if the younger generation tended to prefer modern styles of music.

This decline was changed by the actions of individuals such as American musicologist Alan Lomax, who collected numerous songs in Scotland that were issued by Columbia Records around 1955.

The School of Scottish Studies was founded at University of Edinburgh in 1951, with Henderson as a research fellow and a collection of songs begun by Calum Maclean (1915–1960).

[12] Many progressive folk performers continued to retain a traditional element in their music, including Jansch who became a member of the band Pentangle in 1967.

Particularly important were Donovan (who was most influenced by emerging progressive folk musicians in America such as Bob Dylan) and the Incredible String Band, who from 1967 incorporated a range of influences including medieval and Eastern music into their compositions, leading to the development of psychedelic folk, which had a considerable impact on progressive and psychedelic rock.

[23] Many of these groups played largely music originating from the Lowlands, while later, more successful bands tended to favor the Gaelic sounds of the Highlands.

Out of the wreckage of the latter in 1974, guitarist Dick Gaughan formed probably the most successful band in this genre Five Hand Reel, who combined Irish and Scottish personnel, before he embarked on an influential solo career.

Additionally, groups such as Shooglenifty and Peatbog Faeries mixed traditional highland music with more modern sounds, such as dubstep rhythms, creating a genre sometimes referred to as "Acid Croft".

Successful Scottish stadium rock acts such as Simple Minds from Glasgow and Big Country from Dunfermline incorporated traditional Celtic sounds onto many of their songs.

These groups were influenced by American forms of music, some containing members with no Celtic ancestry and commonly singing in English.