Scranton general strike

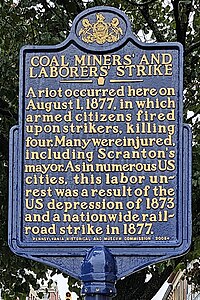

Many had returned to work when violence erupted on August 1 after a mob attacked the town's mayor, and then clashed with local militia, leaving four dead and many more wounded.

[6]: 31 The resulting public dissatisfaction erupted July 14, 1877 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and spread to Maryland, New York, Illinois, Missouri and Pennsylvania.

Making matters worse, the local mining companies had again reduced wages, and railroad and industry owners imposed similar cuts for rail and manufacturing workers.

"[14] On July 23, the workers of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad in Scranton proposed that their wages be restored to that prior to the recently imposed 10% reduction.

On July 24 at 12:00 P.M., 1,000 employees of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, unaffiliated with the railroad, peacefully walked out due to their own wage reduction.

[15] The railroad strike carried implications for the remainder of local industry, as large amounts of goods could not be transported in or out of the city without the use of rail.

"[16] Mayor Robert H. McKune issued a proclamation, urging "all good citizens to use their best efforts to preserve peace and uphold the law," and to "abstain from all excited discussion of the prominent question of the day."

I again earnestly urge upon men of all classes in our city the necessity of sober, careful thought and the criminal folly of any precipitate action.

The railway strikers held a mass meeting and resolved to demand a 25 percent increase in wages, "in order to supply ourselves and our little ones with the necessaries of life.

[18]: 498 On the morning of July 26, Mayor McKune proposed organizing a group of armed special police to help maintain order in the city.

At the time the local militia were stationed across the state in response to railway strike-related struggles occurring in Altoona, Harrisburg, and Pittsburgh.

[22] The Citizens' Corps assembled in the Forest & Stream Sportsman's Club and elected officers, including Ezra H. Ripple as their captain.

During the meeting, an activist showed a forged letter claiming that Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company would reduce wages to $0.35 per day.

[16][17]: 205–6 Note 2 In response, W. W. Scranton (along with First Sergeant Bartholomew, as Captain Ripple was out of town) led an assembly of his own employees and the Citizens' Corps.

At 11:30 AM Mayor McKune issued the following proclamation: I hereby order all places of business to be immediately closed and all good citizens to hold themselves in readiness to assemble at my headquarters, at the office of the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, upon a signal of four long whistles from the gong at the blast furnaces.

[18]: 502 He also wired the Governor, who informed that the National Guard brigade from Philadelphia, which had been on the way home from quelling riots in Pittsburgh, had been diverted and were en route to Scranton.

[18]: 502–3 On August 2 as many as 3,000 troops of the Pennsylvania National Guard First Division arrived from Pittsburgh under the command of Major General Robert Brinton, and imposed martial law.

[16][20]Note 4 The troops had arrested an estimated 70 activists en route, and forced those apprehended to repair places where the railroad tracks between the cities had been destroyed.

[17]: 211–12 Note 5 The Miner's Executive Committee opened a store for families, stocked by the donations of local businessmen and farmers, to relieve those who were suffering as negotiations to end the strike continued.

This prompted a meeting of local businessmen at the Anthracite Club, which resolved that the men of the Corps should be commended for their "courageous efforts" in dispersing the mob and averting calamity, and that they would "stand shoulder and purse if need be in their defense.

"[18]: 506 Governor Hartranft arrived in the city along with his staff and 800 men of the Pennsylvania National Guard Second Division, under the command of General Henry S.

[16]: 190 By this point "outrages" were being committed on a daily basis: Placing obstructions upon the railroads, burning buildings, firing upon watchmen and pump engineers at the mines, and the robbing of arms in the neighborhood.

As W. W. Scranton wrote of the situation: They hold that we are guilty of murder, and with their aldermanic jury's verdict to back them, they would hold a court of Judge Lynch and hang the unfortunate one of us who got into their clutches without an hour's delay, providing they didn't first tear him to pieces ...[17]: 220 The accused were transferred to the custody of the mayor and sheriff and taken by train to appear before the court in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, the county seat of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

In his closing remarks for the defense, Stanley Woodward concluded: We therefore hold that there was a riot, and that these men here charged were in the full heroic performance of their duties as citizens when this unfortunate event occurred.

)[27] Stanton had been sitting judge in 1877 and was arrested for libel in the Scranton case after being implicated by witnesses; he was alleged to have written an "incendiary" piece in the Advocate, "calculated to incite the killing of Mr.

As in numerous US cities, this labor unrest was a result of the US depression of 1873 and a nationwide railroad strike in 1877.Following the uprising, prominent figures in Scranton began advocating for a permanent militia, and within a week nearly a thousand dollars were raised to this effect.

Historians Hitchcock and Downs emphasized the far-reaching effects of the ongoing depression, inflation, rapidly increasing commodity prices, and mass unemployment, as well as the failure of the strikers to appreciate that these conditions affected the employer as well as the employee.

[18]: 504 They go on to suggest that some unknown number of those participating in the ensuing riot may have traveled to Scranton expressly for that purpose, and not in support of the strikers or their objectives.

Historian Michael A. Bellesiles suggested that violence became a type of corporate tool rather than a civic last resort: "management consistently refused to negotiate in any way with their workers and relied entirely on military force to settle the contest.

"[34][35] In contrast, Logan, who was present as events unfolded, dedicates his book on the topic to the "patriotic young men, who had wisdom to discern the city's danger, and the patient courage to provide for its defense.