Scurvy

[6] Scurvy was described as early as the time of ancient Egypt, and historically it was a limiting factor in long-distance sea travel, often killing large numbers of people.

[8] Scurvy is one of the accompanying diseases of malnutrition (other such micronutrient deficiencies are beriberi and pellagra) and thus is still widespread in areas of the world dependent on external food aid.

[16] Scott's 1902 Antarctic expedition used fresh seal meat and increased allowance of bottled fruits, whereby complete recovery from incipient scurvy was reported to have taken less than two weeks.

[31] The Portuguese planted fruit trees and vegetables on Saint Helena, a stopping point for homebound voyages from Asia, and left their sick who had scurvy and other ailments to be taken home by the next ship if they recovered.

[32] In 1500, one of the pilots of Cabral's fleet bound for India noted that in Malindi, its king offered the expedition fresh supplies such as lambs, chickens, and ducks, along with lemons and oranges, due to which "some of our ill were cured of scurvy".

[39] In February 1601, Captain James Lancaster, while commanding the first English East India Company fleet en route to Sumatra, landed on the northern coast of Madagascar specifically to obtain lemons and oranges for his crew to stop scurvy.

[44] A 1609 book by Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola recorded several different remedies for scurvy known at this time in the Moluccas, including a kind of wine mixed with cloves and ginger, and "certain herbs".

[49][50][51] It was not until 1747 that James Lind formally demonstrated that scurvy could be treated by supplementing the diet with citrus fruit, in one of the first controlled clinical experiments reported in the history of medicine.

[52][53] As a naval surgeon on HMS Salisbury, Lind had compared several suggested scurvy cures: hard cider, vitriol, vinegar, seawater, oranges, lemons, and a mixture of balsam of Peru, garlic, myrrh, mustard seed and radish root.

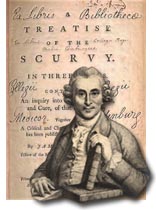

In A Treatise on the Scurvy (1753)[2][54][52] Lind explained the details of his clinical trial and concluded "the results of all my experiments was, that oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea.

[57] Although sailors and naval surgeons were increasingly convinced that citrus fruits could cure scurvy throughout this period, the classically trained physicians who determined medical policy dismissed this evidence as merely anecdotal, as it did not conform to their theories of disease.

The medical theory was based on the assumption that scurvy was a disease of internal putrefaction brought on by faulty digestion caused by the hardships of life at sea and the naval diet.

Advocated by Dr David MacBride and Sir John Pringle, Surgeon General of the Army and later President of the Royal Society, this idea was that scurvy was the result of a lack of 'fixed air' in the tissues which could be prevented by drinking infusions of malt and wort whose fermentation within the body would stimulate digestion and restore the missing gases.

[58] These ideas received wide and influential backing, when James Cook set off to circumnavigate the world (1768–1771) in HM Bark Endeavour, malt and wort were top of the list of the remedies he was ordered to investigate.

The reason for the health of his crews on this and other voyages was Cook's regime of shipboard cleanliness, enforced by strict discipline, and frequent replenishment of fresh food and greenstuffs.

[60] Another beneficial rule implemented by Cook was his prohibition of the consumption of salt fat skimmed from the ship's copper boiling pans, then a common practice elsewhere in the Navy.

[62] Although towards the end of the century, MacBride's theories were being challenged, the medical authorities in Britain remained committed to the notion that scurvy was a disease of internal 'putrefaction' and the Sick and Hurt Board, run by administrators, felt obliged to follow its advice.

Within the Royal Navy, however, opinion – strengthened by first-hand experience with lemon juice at the siege of Gibraltar and during Admiral Rodney's expedition to the Caribbean – had become increasingly convinced of its efficacy.

Ordered to lead an expedition against Mauritius, Rear Admiral Gardner was uninterested in the wort, malt, and elixir of vitriol that were still being issued to ships of the Royal Navy, and demanded that he be supplied with lemons, to counteract scurvy on the voyage.

On 2 May 1794, only HMS Suffolk and two sloops under Commodore Peter Rainier sailed for the east with an outward bound convoy, but the warships were fully supplied with lemon juice and the sugar with which it had to be mixed.

[65] It took a few years before the method of distribution to all ships in the fleet had been perfected and the supply of the huge quantities of lemon juice required to be secured, but by 1800, the system was in place and functioning.

This led to a remarkable health improvement among the sailors and consequently played a critical role in gaining an advantage in naval battles against enemies who had yet to introduce the measures.

[66] The surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon's army at the Siege of Alexandria (1801), Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, wrote in his memoirs that the consumption of horse meat helped the French to curb an epidemic of scurvy.

Its bitter taste was usually disguised with herbs and spices; however, this did not prevent scurvygrass drinks and sandwiches from becoming a popular fad in the UK until the middle of the nineteenth century, when citrus fruits became more readily available.

For example, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 became seriously affected by scurvy when its leader, Adrien de Gerlache, initially discouraged his men from eating penguin and seal meat.

In the Royal Navy's Arctic expeditions in the mid-19th century, it was widely believed that scurvy was prevented by good hygiene on board ship, regular exercise, and maintaining crew morale, rather than by a diet of fresh food.

Navy expeditions continued to be plagued by scurvy even while fresh (not jerked or tinned) meat was well known as a practical antiscorbutic among civilian whalers and explorers in the Arctic.

In the latter half of the 19th century, there was greater recognition of the value of eating fresh meat as a means of avoiding or treating scurvy, but the lack of available game to hunt at high latitudes in winter meant it was not always a viable remedy.

[73] By the early 20th century, when Robert Falcon Scott made his first expedition to the Antarctic (1901–1904), the prevailing theory was that scurvy was caused by "ptomaine poisoning", particularly in tinned meat.

He participated in a study in New York's Bellevue Hospital in February 1928, where he and a companion ate only meat for a year while under close medical observation, yet remained in good health.