Seaplane

Seaplanes were sometimes called hydroplanes,[2] but currently this term applies instead to motor-powered watercraft that use the technique of hydrodynamic lift to skim the surface of water when running at speed.

In the 21st century, seaplanes maintain a few niche uses, such as for aerial firefighting, air transport around archipelagos, and access to undeveloped or roadless areas, some of which have numerous lakes.

The Viking Air DHC-6 Twin Otter and Cessna Caravan utility aircraft have landing gear options which include amphibious floats.

On 28 March 1910, Frenchman Henri Fabre flew the first successful powered seaplane, the Gnome Omega-powered hydravion, a trimaran floatplane.

[9] In 1911−12, François Denhaut constructed the first seaplane with a fuselage forming a hull, using various designs to give hydrodynamic lift at take-off.

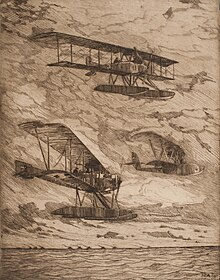

The Wright Brothers, widely celebrated for their breakthrough aircraft designs, were slower to develop a seaplane; Wilbur died in 1912, and the company was bogged down in lawsuits.

Wakefield's pilot, however, taking advantage of a light northerly wind, successfully took off and flew at a height of 50 feet (15 m) to Ferry Nab, where he made a wide turn and returned for a perfect landing on the lake's surface.

Recognising that many of the early accidents were attributable to a poor understanding of handling while in contact with the water, the pair's efforts went into developing practical hull designs to make the transatlantic crossing possible.

[15][16] At the same time, the British boat-building firm J. Samuel White of Cowes on the Isle of Wight set up a new aircraft division and produced a flying boat in the United Kingdom.

The design (later developed into the Model H) resembled Curtiss's earlier flying boats but was built considerably larger so it could carry enough fuel to cover 1,100 mi (1,800 km).

While the craft was found to handle "heavily" on takeoff, and required rather longer take-off distances than expected, the full moon on 5 August 1914 was selected for the trans-Atlantic flight; Porte was to pilot the America with George Hallett as co-pilot and mechanic.

The Curtiss H-4s were soon found to have a number of problems; they were underpowered, their hulls were too weak for sustained operations, and they had poor handling characteristics when afloat or taking off.

Porte modified an H-4 with a new hull whose improved hydrodynamic qualities made taxiing, take-off and landing much more practical and called it the Felixstowe F.1.

Porte's innovation of the "Felixstowe notch" enabled the craft to overcome suction from the water more quickly and break free for flight much more easily.

Meanwhile, the pioneering flying-boat designs of François Denhaut had been steadily developed by the Franco-British Aviation Company into a range of practical craft.

Smaller than the Felixstowes, several thousand FBAs served with almost all of the Allied forces as reconnaissance craft, patrolling the North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean Oceans.

After frequent appeals by the industry for subsidies, the Government decided that nationalization was necessary and ordered five aviation companies to merge to form the state-owned Imperial Airways of London (IAL).

IAL became the international flag-carrying British airline, providing flying-boat passenger and mail-transport links between Britain and South Africa and India using aircraft such as the Short S.8 Calcutta.

In areas where there were no airfields for land-based aircraft, flying boats could stop at small river, lake or coastal stations to refuel and resupply.

The Pan Am Boeing 314 "Clipper" flying boats brought new exotic destinations like the Far East within reach and came to represent the romance of flight.

In that year, government tenders on both sides of the world invited applications to run new passenger and mail services between the ends of the Empire, and Qantas and IAL were successful with a joint bid.

The new ten-day service between Rose Bay, New South Wales, (near Sydney) and Southampton was such a success that the volume of mail soon exceeded aircraft storage space.

It was a four-engined floatplane Mercury (the winged messenger) fixed on top of Maia, a heavily modified Short Empire flying boat.

BOAC continued to operate flying-boat services from the (slightly) safer confines of Poole Harbour during wartime, returning to Southampton in 1947.

[17] When Italy entered the war in June 1940, the Mediterranean was closed to Allied planes and BOAC and Qantas operated the Horseshoe Route between Durban and Sydney using Short Empire flying boats.

The Martin Company produced the prototype XPB2M Mars based on their PBM Mariner patrol bomber, with flight tests between 1941 and 1943.

The first, named Hawaii Mars, was delivered in June 1945, but the Navy scaled back their order at the end of World War II, buying only the five aircraft which were then on the production line.

The ability to land on water became less of an advantage owing to the considerable increase in the number and length of land-based runways during World War II.

[17] The flying boats of Aquila Airways were also chartered for one-off trips, usually to deploy troops where scheduled services did not exist or where there were political considerations.

On 18 December 1990, Pilot Tom Casey completed the first round-the-world flight in a floatplane with only water landings using a Cessna 206 named Liberty II.