Wood drying

The timber of living trees and fresh logs contains a large amount of water which often constitutes over 50% of the wood's weight.

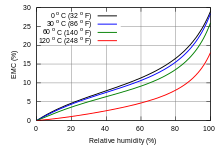

(kg/kg) is dependent on the temperature T (°C) according to the following equation: Keey et al. (2000) use a different definition of the fibre saturation point (equilibrium moisture content of wood in an environment of 99% relative humidity).

Siau (1984) reported that the EMC also varies very slightly with species, mechanical stress, drying history of wood, density, extractives content and the direction of sorption in which the moisture change takes place (i.e. adsorption or desorption).

However, currently used conventional drying processes often result in significant quality problems from cracks, both externally and internally, reducing the value of the product.

[citation needed] Drying, if carried out promptly after felling of trees, also protects timber against primary decay, fungal stain and attack by certain kinds of insects.

However, it is not always easy to relate chemical potential in wood to commonly observable variables, such as temperature and moisture content (Keey et al., 2000).

The vessels in hardwoods are sometimes blocked by the presence of tyloses and/or by secreting gums and resins in some other species, as mentioned earlier.

The presence of gum veins, the formation of which is often a result of natural protective response of trees to injury, is commonly observed on the surface of sawn boards of most eucalypts.

The density is also important for impermeable hardwoods because more cell-wall material is traversed per unit distance, which offers increased resistance to diffusion (Keey et al., 2000).

The transport of fluids is often bulk flow (momentum transfer) for permeable softwoods at high temperature while diffusion occurs for impermeable hardwoods (Siau, 1984).

The chemical potential is explained here since it is the true driving force for the transport of water in both liquid and vapour phases in wood (Siau, 1984).

The diffusion model using the moisture content gradient as a driving force was applied successfully by Wu (1989) and Doe et al. (1994).

The diffusion model is used here based on this empirical evidence that the moisture-content gradient is a driving force for drying this type of impermeable timber.

Furthermore, moisture migrates slowly due to the fact that extractives plug the small cell wall openings in the heartwood.

Although the analysis was done for red oak, the procedure may be applied to any species of wood by adjusting the constant parameters of the model.

Solving for the drying time yields: For example, at 150 °F, using the Arden Buck equation, the saturation vapor pressure of water is found to be about 192 mmHg (25.6 kPa).

Higher temperatures will yield faster drying times, but they will also create greater stresses in the wood due because the moisture gradient will be larger.

Wrapping planks or logs in materials which will allow some movement of moisture, generally works very well provided the wood is first treated against fungal infection by coating in petrol/gasoline or oil.

Mineral oil will generally not soak in more than 1–2 mm below the surface and is easily removed by planing when the timber is suitably dry.

In the process, deliberate control of temperature, relative humidity and air circulation creates variable conditions to achieve specific drying profiles.

To achieve this, the timber is stacked in chambers that are fitted with equipment to control atmospheric temperature, relative humidity and circulation rate (Walker et al., 1993; Desch and Dinwoodie, 1996).

Satisfactory kiln drying can usually be accomplished by regulating the temperature and humidity of the circulating air to control the moisture content of the lumber at any given time.

Low ambient pressure does lower the boiling point of water but the amount of energy required to convert the liquid to vapor is the same.

Because of this, a good vacuum kiln can dry 4.5" thick White Oak fresh off the saw to 8% in less than a month, a feat that was previously thought to be impossible.

Modern high-temperature, high-air-velocity conventional kilns can typically dry 1-inch-thick (25 mm) green lumber in 10 hours down to a moisture content of 18%.

Discontinuous technology allows the entire kiln charge to come up to full atmospheric pressure, the air in the chamber is then heated, and finally vacuum is pulled.

SSV run at partial atmospheres (typically around 1/3 of full atmospheric pressure) in a hybrid of vacuum and conventional kiln technology (SSV kilns are significantly more popular in Europe where the locally harvested wood is easier to dry versus species found in North America).

Since thousands of different types of wood products manufacturing plants exist around the globe, and may be integrated (lumber, plywood, paper, etc.)

Typically, the higher the temperature the kiln operates at, the larger amount of emissions are produced (per pound of water removed).

1910.265(f)(3)(i)(c): Adequate means shall be provided to firmly secure main doors, when they are disengaged from carriers and hangers, to prevent toppling.