Secession in China

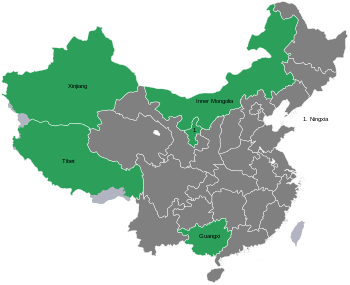

China has historically had tensions between the majority Han and other minority ethnic groups, particularly in rural and border regions.

[1] Kuomintang leader Sun Yat-sen issued a statement calling for the right of self-determination of all Chinese ethnic groups at a party conference in 1924: “The Kuomintang can state with solemnity that it recognizes the right of self-determination of all national minorities in China and it will organize a free and united Chinese republic.”[2] The 1931 constitution of the Chinese Soviet Republic accepted secession as legal, with article 14 stating “The Soviet government of China recognizes the right of self-determination of the national minorities in China, their right to complete separation from China, and to the formation of an independent state for each national minority.” However, the CCP's change from a revolutionary group to the dominant state power in 1949 led to this language being left out of later constitutions and any legal chance for secession disappeared from Chinese law.

[11] During the protests which followed, the pro-democracy camp gained general support alongside the Hong Kong independence movement to a small extent as well.

In 2017, several Chinese media outlets warned against discussion of Macau independence, fearing that speculation would lead to further action.

[13][14][15] The Swedish magazine The Perspective speculated that the relative lack of independence sentiment in Macau stems from the SAR's reliance on gaming and tourism revenue from the Mainland.