Second Battle of the Marne

Following the failure of the German spring offensive to end the conflict, Erich Ludendorff, Chief Quartermaster General, believed that an attack through Flanders would give Germany a decisive victory over the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

To shield his intentions and draw Allied troops away from Belgium, Ludendorff planned for a large diversionary attack along the Marne.

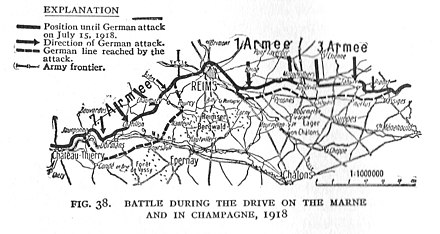

[3] The battle began on 15 July, when 23 German divisions of the First and Third armies – led by Bruno von Mudra and Karl von Einem – assaulted the French Fourth Army under Henri Gouraud east of Reims (the Fourth Battle of Champagne (French: 4e Bataille de Champagne).

[3] East of Reims, the French Fourth Army had prepared a defense in depth to counter an intense bombardment and infiltrating infantry.

German offensive tactics stressed surprise, but French intelligence based on aerial observation gave clear warning and they learned the hour for the attack from twenty-seven prisoners taken in a trench raid.

The attackers moved easily through the French front and then were led onward by a rolling barrage, which soon was well ahead of the infantry because they were held up by the points of resistance.

Some Allied units, particularly Colonel Ulysses G. McAlexander's 38th Infantry Regiment of the American 3rd Infantry Division, the "Rock of the Marne", held fast or even counterattacked, but by evening, the Germans had captured a bridgehead on either side of Dormans 4 mi (6.4 km) deep and 9 mi (14 km) wide, despite the aerial intervention of 225 French bombers, dropping 44 short tons (40 t) of bombs on the makeshift bridges.

A briefcase with false plans for an American countererattack was handcuffed to a man who had died of pneumonia and placed in a vehicle which appeared to have run off the road at a German-controlled bridge.

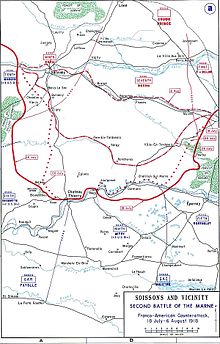

Consequently, the French and American forces led by Foch were able to conduct a different attack on exposed parts of the enemy lines, leaving the Germans with no choice but to retreat.

"[10] However, the presence of fresh American troops, unbroken by years of war, significantly bolstered Allied resistance to the German offensive[citation needed].

On 1 August, French and British divisions of General Charles Mangin's Tenth Army renewed the attack, advancing to a depth of nearly 5 miles (8.0 km).

By this stage, the salient had been reduced and the Germans had been forced back to a line running along the Aisne and Vesle Rivers; the front had been shortened by 28 miles (45 km).