Second Battle of Bull Run

Withdrawing a few miles to the northwest, Jackson took up strong concealed defensive positions on Stony Ridge and awaited the arrival of the wing of Lee's army commanded by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet.

After the collapse of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign in the Seven Days Battles of June 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed John Pope to command the newly formed Army of Virginia.

[17] Pope's mission was to fulfill two basic objectives: protect Washington and the Shenandoah Valley; and draw Confederate forces away from McClellan by moving in the direction of Gordonsville.

Lee's new plan in the face of all these additional forces outnumbering him was to send Jackson and Stuart with half of the army on a flanking march to cut Pope's line of communication, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

The heavy woods allowed the Confederates to conceal themselves, while maintaining good observation points of the Warrenton Turnpike, the likely avenue of Union movement, only a few hundred yards to the south.

This seemingly inconsequential action virtually ensured Pope's defeat during the coming battles because it allowed the two wings of Lee's army to unite on the Manassas battlefield.

The Second Battle of Bull Run began on August 28 as a Federal column, under Jackson's observation just outside Gainesville, near the farm of the John Brawner family, moved along the Warrenton Turnpike.

Hatch's brigade had proceeded past the area and Patrick's men, in the rear of the column, sought cover, leaving Gibbon and Doubleday to respond to Jackson's attack.

Gibbon assumed that, since Jackson was supposedly at Centreville (according to Pope), and having just seen the 14th Brooklyn of Hatch's Brigade reconnoiter the position, that these were merely horse artillery cannons from Jeb Stuart's cavalry.

[29] Gibbon sent aides out to the other brigades with requests for reinforcements, and sent his staff officer Frank A. Haskell to bring the veteran 2nd Wisconsin Infantry up the hill to disperse the harassing cannons.

While some parts of the railroad grade were a good defensive position, others were not, moreover the heavily wooded terrain largely precluded the use of artillery aside from the right end of the line, which faced open fields.

Fitz Lee's cavalry along with a battery of horse artillery were anchoring the left flank of the Confederate line, in case any Union troops attempted to cross Sudley Ford (as McDowell had done during the battle here 13 months earlier) and get in Jackson's rear.

Pope on the 29th remained firmly wedded to the idea that Jackson was in a desperate situation and almost trapped, not only an incorrect assumption, but one that also depended on the coordination of all the corps and divisions under his command, none of which were where he intended them to be.

Having performed poorly in battles against Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley during the spring (and with scant respect or faith from their comrades-in-arms), I Corps' fighting morale was chronically low.

Schenck and Reynolds, subjected to a heavy artillery barrage, answered with counterbattery fire, but avoided a general advance of their infantry, instead merely deploying skirmishers which got into a low-level firefight with Jubal Early's brigade.

Although a hundred or so Confederates came bounding out of the woods in pursuit of Milroy, they were quickly driven back by artillery fire and Stahel returned to his original position south of the turnpike.

[43] Meanwhile, Stuart's cavalry under Col. Thomas Rosser deceived the Union generals by dragging tree branches behind a regiment of horses to simulate great clouds of dust from large columns of marching soldiers.

Meanwhile, to the north, Joseph Carr's brigade had been engaged in a low-level firefight with Confederate troops, in the process wounding Isaac Trimble, one of Jackson's most dependable brigadiers since the Valley Campaign the previous spring.

Trimble's men were routed and began to retreat in disorder, but like all the previous Union attacks during the day, Nagle was unsupported and had no chance against overwhelming enemy numbers.

However, Heintzelman and McDowell conducted a personal reconnaissance that somehow failed to find Jackson's defensive line, and Pope finally made up his mind to attack the retreating Southerners.

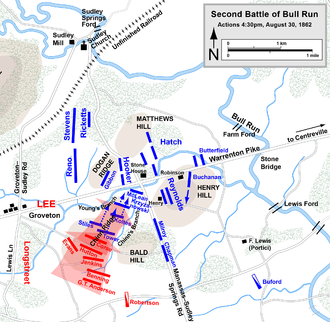

Piatt eventually realized that something was amiss and turned back around towards the battlefield, arriving on Henry House Hill at about 4 p.m. Griffin and his division commander Maj. Gen George W. Morell however stayed at Centreville despite their discovery that Pope was not there.

Eventually, at 4 p.m., Griffin began moving his brigade towards the action, but by this point, Pope's army was in full retreat and a mass of wagons and stragglers were blocking the roadway.

Elements of Hill's and Ewell's divisions came charging out of the woods and surprised some of Ricketts' men with a volley or two, but once again the Union artillery on Dogan Ridge was too much for them and after being blasted by shellfire, they withdrew back to the line of the unfinished railroad.

To support Jackson's exhausted defense, which was stretched to the breaking point, Longstreet's artillery added to the barrage against Union reinforcements attempting to move in, cutting them to pieces.

[57] Lee and Longstreet agreed that the time was right for the long-awaited assault and that the objective would be Henry House Hill, which had been the key terrain in the First Battle of Bull Run, and which, if captured, would dominate the potential Union line of retreat.

"[58] Realizing what was happening down on the left, Porter told Buchanan to instead move in that direction to stem the Confederate onslaught and then also sent a messenger to find the other regular brigade, commanded by Col. Charles W. Roberts and get it into action.

The Zouave regiments had been wearing bright red and blue uniforms, and one of Hood's officers wrote that the bodies lying on the hill reminded him of the Texas countryside when the wildflowers were in bloom.

Although Koltes and Krzyzanowski's six regiments held their ground for a little while, they were quickly overwhelmed by yet more fresh Confederates in the brigades of Lewis Armistead, Montgomery Corse, and Eppa Hunton and started to fall back in disorder.

In 1878, a special commission under General John M. Schofield exonerated Porter by finding that his reluctance to attack Longstreet probably saved Pope's Army of Virginia from an even greater defeat.

The peaceful Virginia countryside bore witness to clashes between the armies of the North (Union) and the South (Confederacy), and it was there that Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson acquired his nickname "Stonewall".