Second International

The organization continued the work of the First International, which had been dissolved in 1876, and was ideologically dominated by Marxism, although other viewpoints were represented, most notably anarchism until anarchists were expelled in 1893.

Its key thinkers included Friedrich Engels, Karl Kautsky, and Georgi Plekhanov, with the ideas of Vladimir Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg also being influential.

The question of reform or revolution to achieve socialism resolved against revisionist thinker Eduard Bernstein, who argued for a gradualist and electoralist strategy.

However, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 saw the international split into pro-Allied, pro-Central Powers, and antimilitarist factions and cease to function by 1916.

The Possibilists insisted upon recording the names and documentation of delegates so as to verify their mandate, while the Marxists (many of whom faced conditions of illegality at home) were concerned about information being discovered by the authorities.

[6] However, according to John Burns, William Morris, and some of the Marxist delegates, there were no real concerns around verification until Henry Hyndman proposed the measure, and the dispute was a deliberate ploy to split the congress in two, an allegation strongly rebuked by Annie Besant.

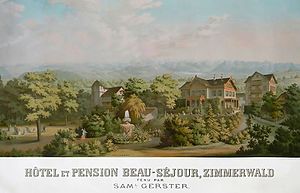

[7][8][9] Regardless of which account is true, the split between the Possibilists and Marxists threatened to create two separate internationals, with subsequent conferences in Brussels and Zürich respectively.

However, after the anger aroused during the split congresses had died down, the Marxists ultimately agreed to join the Brussels conference and create a single, unified international.

At the founding of the international, Paul Lafargue affirmed that socialists were "brothers with a single common enemy [...] private capital, whether it be Prussian, French, or Chinese.

"[13] The extraordinary congress in Basel in 1912 was largely devoted to a discussion of rising militarism, which resulted in a manifesto stating that the working classes should "exert every effort in order to prevent the outbreak of war by the means they consider most effective.

This took many socialist parties in neutral countries by surprise, such as the Romanian Social Democrats, who initially refused to print the SPD's endorsement of war, believing it to be a forgery.

The conflict between anarchist and Marxist factions dated back to the days of the First International, which was frequently characterized by clashes between the state socialists (ie.

Tensions reached their peak after the Hague Congress of 1872, wherein an attempt was made to expel Mikhail Bakunin and James Guillaume and move the general council to New York City, effectively disbanding the organization.

Superprofits extracted from colonized areas were diverted to the advanced countries, whereupon a portion was given over to a labor aristocracy as a "bribe", in the form of higher wages.

The Bolsheviks saw this privileged, highly-skilled strata of workers organized into craft unions as a threat within the labor movement, which would try to take leadership positions in order to gain higher wages at the expense of other proletarians.

Plekhanov generally agreed with the Entente, believing that German warmongering was a criminal act that needed to be punished by an international coalition.

While the pre-war international was relatively consistent in its opposition to an inter-imperialist conflict between European powers, it was often paternalistic towards colonial areas, and statements often mentioned a need to educate or civilize conquered peoples.

By the Stuttgart congress of 1907, parties in the international had substantially shifted away from their earlier consensus on ostensible anticolonialism towards a mix of overtly pro-colonial, anti-colonial and neutral views.

These divisions were made apparent in a proposal by the Dutch delegate Henri van Kol that the international drop its anticolonial position, which was defeated 128 votes to 108.

[32] From its outset, one of the objectives of the international was to build a consensus on the "Jewish question", a contemporary term for debates on the civil, legal, national, and political status and treatment of Jews as a minority group.

In addition to antisemitism against Jewish bankers and capitalists, the British socialist newspaper Justice reported that "[t]here appears to be a strong feeling against the Jews in the Congress.