Second law of thermodynamics

A simple statement of the law is that heat always flows spontaneously from hotter to colder regions of matter (or 'downhill' in terms of the temperature gradient).

[4] An increase in the combined entropy of system and surroundings accounts for the irreversibility of natural processes, often referred to in the concept of the arrow of time.

Statistical mechanics provides a microscopic explanation of the law in terms of probability distributions of the states of large assemblies of atoms or molecules.

[7][8] The first rigorous definition of the second law based on the concept of entropy came from German scientist Rudolf Clausius in the 1850s and included his statement that heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

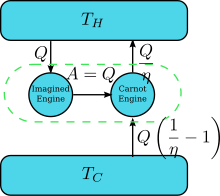

Some samples from his book are: In modern terms, Carnot's principle may be stated more precisely: The German scientist Rudolf Clausius laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics in 1850 by examining the relation between heat transfer and work.

[36] His formulation of the second law, which was published in German in 1854, is known as the Clausius statement: Heat can never pass from a colder to a warmer body without some other change, connected therewith, occurring at the same time.

[48] Though it is almost customary in textbooks to say that Carathéodory's principle expresses the second law and to treat it as equivalent to the Clausius or to the Kelvin-Planck statements, such is not the case.

[58] That is, when a system is described by stating its internal energy U, an extensive variable, as a function of its entropy S, volume V, and mol number N, i.e. U = U (S, V, N), then the temperature is equal to the partial derivative of the internal energy with respect to the entropy[59] (essentially equivalent to the first TdS equation for V and N held constant): The Clausius inequality, as well as some other statements of the second law, must be re-stated to have general applicability for all forms of heat transfer, i.e. scenarios involving radiative fluxes.

For the emission of NBR, including graybody radiation (GR), the resultant emitted entropy flux, or radiance L, has a higher ratio of entropy-to-energy (L/K), than that of BR.

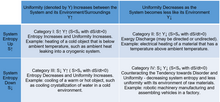

Where 'exergy' is the thermal, mechanical, electric or chemical work potential of an energy source or flow, and 'instruction or intelligence', although subjective, is in the context of the set of category IV processes.

The robotic machinery requires electrical work input and instructions, but when completed, the manufactured products have less uniformity with their surroundings, or more complexity (higher order) relative to the raw materials they were made from.

Unconstrained heat transfer can spontaneously occur, leading to water molecules freezing into a crystallized structure of reduced disorder (sticking together in a certain order due to molecular attraction).

This is possible provided the total entropy change of the system plus the surroundings is positive as required by the second law: ΔStot = ΔS + ΔSR > 0.

For the three examples given above: For a spontaneous chemical process in a closed system at constant temperature and pressure without non-PV work, the Clausius inequality ΔS > Q/Tsurr transforms into a condition for the change in Gibbs free energy or dG < 0.

This is the most useful form of the second law of thermodynamics in chemistry, where free-energy changes can be calculated from tabulated enthalpies of formation and standard molar entropies of reactants and products.

Recognizing the significance of James Prescott Joule's work on the conservation of energy, Rudolf Clausius was the first to formulate the second law during 1850, in this form: heat does not flow spontaneously from cold to hot bodies.

Established during the 19th century, the Kelvin-Planck statement of the second law says, "It is impossible for any device that operates on a cycle to receive heat from a single reservoir and produce a net amount of work."

Because of the looseness of its language, e.g. universe, as well as lack of specific conditions, e.g. open, closed, or isolated, many people take this simple statement to mean that the second law of thermodynamics applies virtually to every subject imaginable.

In terms of time variation, the mathematical statement of the second law for an isolated system undergoing an arbitrary transformation is: where The equality sign applies after equilibration.

However, for systems with a small number of particles, thermodynamic parameters, including the entropy, may show significant statistical deviations from that predicted by the second law.

The second part of the second law states that the entropy change of a system undergoing a reversible process is given by: where the temperature is defined as: See Microcanonical ensemble for the justification for this definition.

for the canonical ensemble in here gives: As elaborated above, it is thought that the second law of thermodynamics is a result of the very low-entropy initial conditions at the Big Bang.

Commonly, systems for which gravity is not important have a positive heat capacity, meaning that their temperature rises with their internal energy.

In general, a region of space containing a physical system at a given time, that may be found in nature, is not in thermodynamic equilibrium, read in the most stringent terms.

In all cases, the assumption of thermodynamic equilibrium, once made, implies as a consequence that no putative candidate "fluctuation" alters the entropy of the system.

It can easily happen that a physical system exhibits internal macroscopic changes that are fast enough to invalidate the assumption of the constancy of the entropy.

For non-equilibrium situations in general, it may be useful to consider statistical mechanical definitions of other quantities that may be conveniently called 'entropy', but they should not be confused or conflated with thermodynamic entropy properly defined for the second law.

In the opinion of Schrödinger, "It is now quite obvious in what manner you have to reformulate the law of entropy – or for that matter, all other irreversible statements – so that they be capable of being derived from reversible models.

Good examples of this are the Ladder Paradox, time dilation and length contraction exhibited by objects approaching the velocity of light or within proximity of a super-dense region of mass/energy - e.g. black holes, neutron stars, magnetars and quasars.

Szilárd pointed out that a real-life Maxwell's demon would need to have some means of measuring molecular speed, and that the act of acquiring information would require an expenditure of energy.