Secret Gospel of Mark

This letter, in turn, is preserved only in photographs of a Greek handwritten copy seemingly transcribed in the 18th century into the endpapers of a 17th-century printed edition of the works of Ignatius of Antioch.

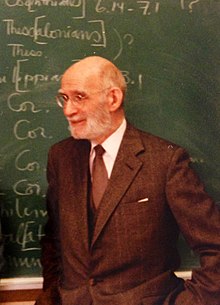

In 1958, Morton Smith, a professor of ancient history at Columbia University, found a previously unknown letter of Clement of Alexandria in the monastery of Mar Saba situated 20 kilometres (12 miles) south-east of Jerusalem.

[42] During a trip to Jordan, Israel, Turkey, and Greece in the summer of 1958 "hunting for collections of manuscripts",[44] Morton Smith also visited the Greek Orthodox monastery of Mar Saba[45] situated between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea.

[10][61][d] In the following years, he made a thorough study of Mark, Clement and the letter's background and relationship to early Christianity,[56] during which time he consulted many experts in the relevant fields.

In 1966 he had basically completed his study, but the result in the form of the scholarly book Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark[63] was not published until 1973 due to seven years of delay "in the production stage".

Stroumsa, along with the late Hebrew University professors David Flusser and Shlomo Pines and Greek Orthodox Archimandrite Meliton, went to Mar Saba to look for the book.

With the help of a Mar Saba monk, they relocated it where Smith presumably had left it 18 years earlier, and with "Clement's letter written on the blank pages at the end of the book".

To refute the teachings of the gnostic sect of Carpocratians, known for their sexual libertinism,[97][98] and to show that these words were absent in the true Secret Gospel of Mark, Clement quoted two passages from it.

[113][12][114][115] Smith argued that the Christian movement began as a mystery religion[67] with baptismal initiation rites,[g][96] and that the historical Jesus was a magus possessed by the Spirit.

Quesnell and others have argued that this fact supports the supposition that the book never was part of the Mar Saba library,[140] but was brought there from outside, by for example Smith, with the text already inscribed.

[149] Murgia found Clement's exhortation to Theodore, that he should not concede to the Carpocratians "that the secret Gospel is by Mark, but should even deny it on oath",[19] to be ludicrous, since there is no point in "urging someone to commit perjury to preserve the secrecy of something which you are in the process of disclosing".

[q] In the main, the Clementine scholars have accepted the authenticity of the letter, and in 1980 it was also included in the concordance of the acknowledged genuine writings of Clement,[133][28] although the inclusion is said by the editor Ursula Treu to be provisional.

[213] Martínez finds Watson's methods, by which he reaches the conclusion that "[t]here is no alternative but to conclude that Smith is dependent on" The Mystery of Mar Saba,[214] to be "surreal as a work of scholarship".

[241] The same year Stephen C. Carlson published The Gospel Hoax[242] in which he spells out his case that Morton Smith, himself, was both the author and the scribe of the Mar Saba manuscript.

"[245] Brown also criticized the pastiche theory, according to which Secret Mark would be created from a patchwork of phrases from especially the Synoptic Gospels, for being speculative, uncontrollable and "unrealistically complicated".

"[250] In The Gospel Hoax (2005),[242] Stephen C. Carlson argued that Clement's letter to Theodore is a forgery and only Morton Smith could have forged it, as he had the "means, motive, and opportunity" to do so.

[u] Craig A. Evans, for instance, came to think that "the Clementine letter and the quotations of Secret Mark embedded within it constitute a modern hoax, and Morton Smith almost certainly is the hoaxer.

Carlson chose "to use the halftone reproductions found in [Smith's book] Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark" where the images were printed with a line screen made of dots.

[279] Jeffery reads the Secret Mark story as an extended double entendre that tells "a tale of 'sexual preference' that could only have been told by a twentieth-century Western author"[280] who inhabited "a homoerotic subculture in English universities".

[284] In 2008, extensive correspondence between Smith and his teacher and lifelong friend Gershom Scholem was published, where they for decades discuss Clement's letter to Theodore and Secret Mark.

[285] The book's editor, Guy Stroumsa, argues that the "correspondence should provide sufficient evidence of his [i.e., Smith's] intellectual honesty to anyone armed with common sense and lacking malice.

[295] Craig Evans argues that Smith before the discovery had published three studies, in 1951,[296] 1955[297] and 1958,[298] in which he discussed and linked "(1) "the mystery of the kingdom of God" in Mark 4:11, (2) secrecy and initiation, (3) forbidden sexual, including homosexual, relationships and (4) Clement of Alexandria".

Forbidden sexual relations, such as "incest, intercourse during menstruation, adultery, homosexuality, and bestiality", is just one subject among several others in the scriptures that the Tannaim deemed should be discussed in secret.

[309] Helmut Koester writes that Morton Smith "was not a good form-critical scholar" and that it "would have been completely beyond his ability to forge a text that, in terms of form-criticism, is a perfect older form of the same story as appears in John 11 as the raising of Lazarus.

[aa] However, Agamemnon Tselikas, a distinguished Greek paleographer[ab] and thus a specialist in deciding when a particular text was written and in what school this way of writing was taught, thought the letter was a forgery.

According to Kotansky, Smith "certainly could not have produced either the Greek cursive script of the Mar Saba manuscript, nor its grammatical text" and writes that few are "up to this sort of task";[321] which, if the letter is forged, would be "one of the greatest works of scholarship of the twentieth century", according to Bart Ehrman.

Geoffrey Smith and Landau believe the letter was composed in the context of a late antique controversy raging in Palestinian monasteries like Mar Saba over adelphopoiesis, or "brother-making," a ceremony which recognized an intense emotional and spiritual relationship (not necessarily erotic, though sometimes viewed as such by contemporaries and modern observers) between two monks.

[336][i] In his later work, Morton Smith increasingly came to see the historical Jesus as practicing some type of magical rituals and hypnotism,[26][68] thus explaining various healings of demoniacs in the gospels.

[372] The resurrection of the young man by Jesus in Secret Mark bears such clear similarities to the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John (11:1–44) that it can be seen as another version of that story.

[374][386][387][388] Michael Kok thinks that this also militates against the thesis that the Gospel of John depends on Secret Mark and that it indicates that they both are based either on "oral variants of the same underlying tradition",[389] or on older written collections of miracle stories.