Section 116 of the Constitution of Australia

The issues of religious freedom and secularism were not prominent in the convention debates, which focused on the economic and legislative powers of the proposed Commonwealth parliament.

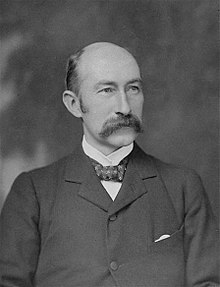

[7] At the Melbourne Convention of 1897, Victorian delegate H. B. Higgins expressed concern about this assumption and moved to expand the provision to cover the Commonwealth as well as the states.

[11] Both sides to some extent achieved their objectives: Section 116 was approved by the final convention, while Glynn successfully moved for the symbolic mention of "Almighty God" in the preamble to the British statute that was to contain the Constitution.

[20] As a result of the court's narrow and literal interpretation of Section 116, the provision has played a minor role in Australian constitutional history.

[18] The leading authority on the question is the 1983 judgment of the High Court in Church of the New Faith v Commissioner for Pay-Roll Tax (Vic).

[31] In 1912, the court in Krygger v Williams,[32] held that a person could not object to compulsory military service on the ground of religious belief.

In a 1929 case, Higgins, then a Justice of the High Court, suggested (as obiter dictum) that a person could lawfully object to compulsory voting on the grounds of religious belief.

[33] However, in 1943, the court continued the narrow approach it took in Krygger v Williams, upholding war-time regulations that caused the Adelaide branch of the Jehovah's Witnesses to be dissolved and have its property acquired by the Commonwealth government.

Chief Justice John Latham held that the Constitution permitted the court to "reconcile religious freedom with ordered government".

[38] In her judgment, Gaudron J, while finding that the provision "cannot be construed as impliedly conferring an independent or free-standing right which, if breached, sounds in damages at the suit of the individual whose interests are thereby affected" left open the possibility that it might nonetheless, in limiting Commonwealth legislative power, apply to a provision that has the effect, as opposed merely to the purpose, of limiting free exercise.

Pannam considered the provision would only become significant if the High Court held that it applied to laws made by governments of the territories.

Williams argues that as an "express guarantee of personal freedom", the provision should be interpreted broadly and promote "individual liberty over the arbitrary exercise of legislative and executive power".

[21] Academics Gonzalo Villalta Puig and Steven Tudor have called for the court to broaden Section 116 by finding in it an implied right to the freedom of thought and conscience.

In 1944, John Curtin's Labor government put a package of measures, known as the "Fourteen Powers referendum", to the Australian public.

[15] The package's 14 measures—which included diverse matters such as powers to provide family allowances and legislate for "national health"—were bound together in a single question.

[46] Arthur Fadden, leader of the Country Party, claimed a "yes" vote would permit the government to implement a "policy of socialisation".

The proposal in respect of Section 116 was to extend its operation to the states,[51] and expand the protection to cover any government act (not just legislation) that established a religion or prohibited its free exercise.

[55] Williams attributes the failure of the proposal mainly to the absence of bipartisan support for it, highlighting the "determined and effective" opposition of senior Liberal Party politician Peter Reith.