Sejny Uprising

The uprising did not solve the larger border conflict between Poland and Lithuania over the ethnically mixed Suwałki Region.

[7][8] During World War I, the region was captured by the German Empire, which intended to incorporate the area into its province of East Prussia.

[2] In July 1919, when the German troops began their slow retreat from the area, they delegated the administration to local Lithuanian authorities.

[10] Lithuanian officers and troops, who first arrived in the region in May,[11] began to organize military units in the pre-war Sejny county.

[12] It is generally agreed that Lithuanians formed the majority of the population in the northern Suwałki Governorate, while Poles were concentrated in the south.

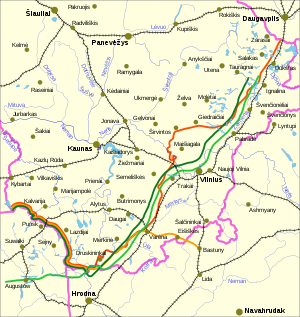

[14] In the aftermath of World War I, the Conference of Ambassadors drew the first demarcation line between Poland and Lithuania on June 18, 1919.

[16] The Foch Line was negotiated with the Polish war mission, led by General Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski in Paris, while Lithuanian representatives were not invited.

[1] The Poles hoped to capture the territory up to the Foch Line and advance further to take control of the towns of Seirijai, Lazdijai, Kapčiamiestis as far as Simnas.

[2][23] According to the Polish historian Tadeusz Mańczuk, Piłsudski – who was planning a coup d'état in Kaunas – discouraged the local PMO activists from carrying out the Sejny Uprising.

[2] Piłsudski reasoned that any hostilities could leave Lithuanians even more opposed to the proposed union with Poland (see Międzymorze).

"[1][24] On August 20, Prime Minister of Lithuania Mykolas Sleževičius visited Sejny and called on Lithuanians to defend their lands "to the end, however they can, with axes, pitchforks and scythes".

[1][24] According to Lesčius, at the time the Lithuanian command in Sejny had only 260 infantry and 70 cavalry personnel, stretched along the long line of defense.

[2] On the evening of August 25, the first regular unit (41st Infantry Regiment) of the Polish Army received an order to advance towards Sejny.

[27] The Polish regular army units did not cross the Foch Line, and refused to aid the PMO insurgents still operating on the Lithuanian side.

[11][28] The New York Times, reporting on renewed hostilities a year later, described the 1919 Sejny events as a violent occupation by the Poles, in which the Lithuanian inhabitants, teachers, and religious ministers were maltreated and expelled.

[29] Polish historian Łossowski notes that both sides mistreated the civilian population and exaggerated reports to gain internal and foreign support.

[2][9] After the uprising, the Lithuanian police and intelligence intensified their investigation of Polish sympathizers and soon uncovered the planned coup.

During the investigations, lists of PMO supporters were found; law enforcement completely suppressed the organisation in Lithuania.

When the Polish Army began to retreat during the course of the Polish–Soviet War, the Lithuanians moved to secure what they claimed to be their new borders, set by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty of July 1920.

[6] The situation was legalized by the Suwałki Agreement of October 7, 1920, which effectively returned the town to the Polish side of the border.