Self-knowledge (psychology)

Self-knowledge is a term used in psychology to describe the information that an individual draws upon when finding answers to the questions "What am I like?"

While seeking to develop the answer to this question, self-knowledge requires ongoing self-awareness and self-consciousness (which is not to be confused with consciousness).

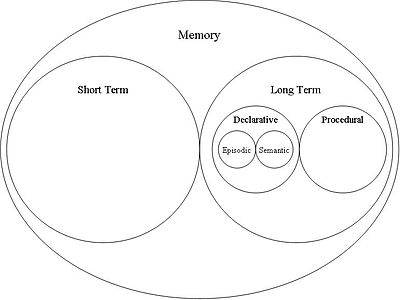

Self-knowledge and its structure affect how events we experience are encoded, how they are selectively retrieved/recalled, and what conclusions we draw from how we interpret the memory.

The connection between our memory and our self-knowledge has been recognized for many years by leading minds in both philosophy[6] and psychology,[7][8] yet the precise specification of the relation remains a point of controversy.

Instead it includes the memory of meanings, understandings, general knowledge about the world, and factual information etc.

This evidence for the dissociation between episodic and semantic self-knowledge has made several things clear: People have goals that lead them to seek, notice, and interpret information about themselves.

The emphasis on feelings differs slightly from how other theories have previously defined self-enhancement needs, for example the Contingencies of Self-Worth Model.

[22][23] In many situations and cultures, feelings of self-worth are promoted by thinking of oneself as highly capable or better than one's peers.

In Western societies, feelings of self-worth are in fact promoted by thinking of oneself in favorable terms.

[24] There are three considerations which underlie this need:[25] Accurate self-knowledge can also be instrumental in maximizing feelings of self-worth.

This is because self-enhancement needs can be met by knowing that one can not do something particularly well, thus protecting the person from pursuing a dead-end dream that is likely to end in failure.

The theory states that once a person develops an idea about what they are like, they will strive to verify the accompanying self-views.

This is in stark contrast to self-enhancement motives that suggest people are driven by the desire to feel good about themselves.

The need for accurate self-knowledge was originally thought to guide the social comparison process, and researchers assumed that comparing with others who are similar to us in the important ways is more informative.

The process was first explained by the sociologist Charles H. Cooley in 1902 as part of his discussion of the "looking-glass self", which describes how we see ourselves reflected in other peoples' eyes.

[38] He argued that a person's feelings towards themselves are socially determined via a three-step process: "A self-idea of this sort seems to have three principled elements: the imagination of our appearance to the other person; the imagination of his judgment of that appearance; and some sort of self-feeling, such as pride or mortification.

In 1963, John W. Kinch adapted Cooley's model to explain how a person's thoughts about themselves develop rather than their feelings.

Research has only revealed limited support for the models and various arguments raise their heads: The sequence of reflected appraisals may accurately characterize patterns in early childhood due to the large amount of feedback infants receive from their parents, yet it appears to be less relevant later in life.

Once a person's ideas about themselves take shape, these also influence the manner in which new information is gathered and interpreted, and thus the cycle continues.

There are three processes that influence how people acquire knowledge about themselves: Introspection involves looking inwards and directly consulting our attitudes, feelings and thoughts for meaning.

Generally, introspection relies on people's explanatory theories of the self and their world, the accuracy of which is not necessarily related to the form of self-knowledge that they are attempting to assess.

[45] Participants in an introspection condition are less accurate when predicting their own future behavior than controls[46] and are less satisfied with their choices and decisions.

[47] In addition, it is important to notice that introspection allows the exploration of the conscious mind only, and does not take into account the unconscious motives and processes, as found and formulated by Freud.

Under particular conditions, people have been shown to infer their attitudes,[49] emotions,[50] and motives,[51] in the same manner described by the theory.

With self-perception processes we indirectly infer our attitudes, feelings, and motives by analyzing our behavior.

Self-concept, or how people usually think of themselves is the most important personal factor that influences current self-representation.