Optical telegraph

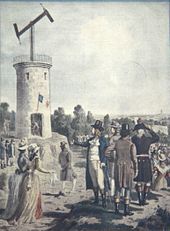

"[20][21] Credit for the first successful optical telegraph goes to the French engineer Claude Chappe and his brothers in 1792, who succeeded in covering France with a network of 556 stations stretching a total distance of 4,800 kilometres (3,000 mi).

During 1790–1795, at the height of the French Revolution, France needed a swift and reliable military communications system to thwart the war efforts of its enemies.

France was surrounded by the forces of Britain, the Netherlands, Prussia, Austria, and Spain, the cities of Marseille and Lyon were in revolt, and the British Fleet held Toulon.

In mid-1790, the Chappe brothers set about devising a system of communication that would allow the central government to receive intelligence and to transmit orders in the shortest possible time.

[24] The Chappes carried out experiments during the next two years, and on two occasions their apparatus at Place de l'Étoile, Paris was destroyed by mobs who thought they were communicating with royalist forces.

In the summer of 1792 Claude was appointed Ingénieur-Télégraphiste and charged with establishing a line of stations between Paris and Lille, a distance of 230 kilometres (about 143 miles).

[1] English military engineer William Congreve observed that at the Battle of Vervik of 1793 French commanders directed their forces by using the sails of a prominent local windmill as an improvised signal station.

Their semaphore was composed of two black movable wooden arms, connected by a cross bar; the positions of all three of these components together indicated an alphabetic letter.

In this manner, each symbol could propagate down the line as quickly as operators could successfully copy it, with acknowledgement and flow control built into the protocol.

For instance, based on Rousseau's argument that direct democracy was improbable in large constituencies, the French Intellectual Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde commented: Something has been said about the telegraph which appears perfectly right to me and gives the right measure of its importance.

[36] In 1819 Norwich Duff, a young British Naval officer, visiting Clermont-en-Argonne, walked up to the telegraph station there and engaged the signalman in conversation.

Here is his note of the man's information:[37] The pay is twenty five sous per day and he [the signalman] is obliged to be there from day light till dark, at present from half past three till half past eight; there are only two of them and for every minute a signal is left without being answered they pay five sous: this is a part of the branch which communicates with Strasburg and a message arrives there from Paris in six minutes it is here in four.

Tours was chosen because it was a division station where messages were purged of errors by an inspector who was privy to the secret code used and unknown to the ordinary operators.

A new line along the coast from Kullaberg to Malmö, incorporating the Helsingborg link, was planned in support and to provide signalling points to the Swedish fleet.

Nelson's attack on the Danish fleet at Copenhagen in 1801 was reported over this link, but after Sweden failed to come to Denmark's aid it was not used again and only one station on the supporting line was ever built.

After Sweden ceded Finland in the Treaty of Fredrikshamn, the east coast telegraph stations were considered superfluous and put into storage.

The Corps head, Carl Fredrik Akrell, conducted comparisons of the Swedish shutter telegraph with more recent systems from other countries.

In operation by 1800, it ran between the city of Halifax and the town of Annapolis in Nova Scotia, and across the Bay of Fundy to Saint John and Fredericton in New Brunswick.

The Duke had envisioned the line reaching as far as the British garrison at Quebec City, but the many hills and coastal fog meant the towers needed to be placed relatively close together to ensure visibility.

The labour needed to build and continually man so many stations taxed the already stretched-thin British military and there is doubt the New Brunswick line was ever in operation.

Initially, it was planned that semaphore stations be established on the bell towers and domes of the island's churches, but the religious authorities rejected the proposal.

In 1833 Charles O'Hara Booth took over command of the Port Arthur penal settlement, as an "enthusiast in the art of signalling" [83] he saw the value of better communications with the headquarters in Hobart.

In the north of the state there was a requirement to report on shipping arrivals as they entered the Tamar Estuary, some 55 kilometers from the main port at this time in Launceston.

[88] In Spain, the engineer Agustín de Betancourt developed his own system which was adopted by that state; in 1798 he received a Royal Appointment,[89] and the first stretch of line connecting Madrid and Aranjuez was in operation as of August 1800.

These lines served many other Spanish cities, including: Aranjuez, Badajoz, Burgos, Castellon, Ciudad Real, Córdoba, Cuenca, Gerona, Pamplona, San Sebastian, Seville, Tarancon, Taragona, Toledo, Valladolid, Valencia, Vitoria and Zaragoza.

The innovative Portuguese telegraphs, designed by Francisco António Ciera [pt], a mathematician, were of 3 types: 3 shutters, 3 balls and 1 pointer/moveable arm.

For example, the UK and Sweden adopted systems of shuttered panels (in contradiction to the Chappe brothers' contention that angled rods are more visible).

[102] In Russia, Tsar Nicolas I inaugurated a line between Moscow and Warsaw of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) length in 1833; it needed 220 stations staffed by 1,320 operators.

In "Mister Pencil" (1831), a comic strip by Rodolphe Töpffer, a dog fallen on a Chappe telegraph's arm—and its master attempting to help get it down—provoke an international crisis by inadvertently transmitting disturbing messages.

In Hector Malot's novel Romain Kalbris (1869), one of the characters, a girl named Dielette, describes her home in Paris as "...next to a church near which there was a clock tower.