Semitic languages

The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history, who derived the name from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

The languages were familiar to Western European scholars due to historical contact with neighbouring Near Eastern countries and through Biblical studies, and a comparative analysis of Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic was published in Latin in 1538 by Guillaume Postel.

[5][page needed] The term "Semitic" was created by members of the Göttingen school of history, initially by August Ludwig von Schlözer (1781), to designate the languages closely related to Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew.

In contrast, all so called Hamitic peoples originally used hieroglyphs, until they here and there, either through contact with the Semites, or through their settlement among them, became familiar with their syllabograms or alphabetic script, and partly adopted them.

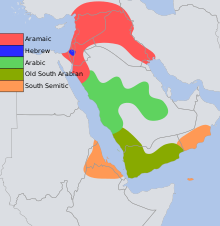

Several locations were proposed as possible sites of a prehistoric origin of Semitic-speaking peoples: Mesopotamia, the Levant, Ethiopia,[15] the Eastern Mediterranean region, the Arabian Peninsula, and North Africa.

They were spoken in what is today Israel and the Palestinian territories, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, the northern Sinai Peninsula, some northern and eastern parts of the Arabian Peninsula, southwest fringes of Turkey, and in the case of Phoenician, coastal regions of Tunisia (Carthage), Libya, Algeria, and parts of Morocco, Spain, and possibly in Malta and other Mediterranean islands.

[citation needed] Old South Arabian languages (classified as South Semitic and therefore distinct from the Central-Semitic Arabic) were spoken in the kingdoms of Dilmun, Sheba, Ubar, Socotra, and Magan, which in modern terms encompassed part of the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and Yemen.

The Arabic language, although originating in the Arabian Peninsula, first emerged in written form in the 1st to 4th centuries CE in the southern regions of The Levant.

The Arabs spread their Central Semitic language to North Africa (Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and northern Sudan and Mauritania), where it gradually replaced Egyptian Coptic and many Berber languages (although Berber is still largely extant in many areas), and for a time to the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain, Portugal, and Gibraltar) and Malta.

[citation needed] With the patronage of the caliphs and the prestige of its liturgical status, Arabic rapidly became one of the world's main literary languages.

Its spread among the masses took much longer, however, as many (although not all) of the native populations outside the Arabian Peninsula only gradually abandoned their languages in favour of Arabic.

As Bedouin tribes settled in conquered areas, it became the main language of not only central Arabia, but also Yemen,[27] the Fertile Crescent, and Egypt.

Most of the Maghreb followed, specifically in the wake of the Banu Hilal's incursion in the 11th century, and Arabic became the native language of many inhabitants of al-Andalus.

A number of Modern South Arabian languages distinct from Arabic still survive, such as Soqotri, Mehri and Shehri which are mainly spoken in Socotra, Yemen, and Oman.

Successful as second languages far beyond their numbers of contemporary first-language speakers, a few Semitic languages today are the base of the sacred literature of some of the world's major religions, including Islam (Arabic), Judaism (Hebrew and Aramaic (Biblical and Talmudic)), churches of Syriac Christianity (Classical Syriac) and Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Christianity (Geʽez).

[28][29][30][31][32] Koine Greek and Classical Arabic are the main liturgical languages of Oriental Orthodox Christians in the Middle East, who compose the patriarchates of Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria.

Biblical Hebrew, long extinct as a colloquial language and in use only in Jewish literary, intellectual, and liturgical activity, was revived in spoken form at the end of the 19th century.

A number of Gurage languages are spoken by populations in the semi-mountainous region of central Ethiopia, while Harari is restricted to the city of Harar.

Note that Latin letter values (italicized) for extinct languages are a question of transcription; the exact pronunciation is not recorded.

Most of the attested languages have merged a number of the reconstructed original fricatives, though South Arabian retains all fourteen (and has added a fifteenth from *p > f).

In Aramaic and Hebrew, all non-emphatic stops occurring singly after a vowel were softened to fricatives, leading to an alternation that was often later phonemicized as a result of the loss of gemination.

Note: the fricatives *s, *z, *ṣ, *ś, *ṣ́, and *ṱ may also be interpreted as affricates (/t͡s/, /d͡z/, /t͡sʼ/, /t͡ɬ/, /t͡ɬʼ/, and /t͡θʼ/).Notes: The following table shows the development of the various fricatives in Hebrew, Aramaic, Arabic and Maltese through cognate words: – żmien xahar sliem tnejn – */d/ d daħaq – ħolm għarb sebgħa Proto-Semitic vowels are, in general, harder to deduce due to the nonconcatenative morphology of Semitic languages.

The proto-Semitic three-case system (nominative, accusative and genitive) with differing vowel endings (-u, -a -i), fully preserved in Qur'anic Arabic (see ʾIʿrab), Akkadian and Ugaritic, has disappeared everywhere in the many colloquial forms of Semitic languages.

Modern Standard Arabic maintains such case distinctions, although they are typically lost in free speech due to colloquial influence.

Classical Arabic still has a mandatory dual (i.e. it must be used in all circumstances when referring to two entities), marked on nouns, verbs, adjectives and pronouns.

It is not generally agreed whether the systems of the various Semitic languages are better interpreted in terms of tense, i.e. past vs. non-past, or aspect, i.e. perfect vs. imperfect.

A special feature in classical Hebrew is the waw-consecutive, prefixing a verb form with the letter waw in order to change its tense or aspect.

This root also exists in Arabic and is used to form words with a close meaning to "writing", such as ṣaḥāfa "journalism", and ṣaḥīfa "newspaper" or "parchment".

Verbs in other non-Semitic Afroasiatic languages show similar radical patterns, but more usually with biconsonantal roots; e.g. Kabyle afeg means "fly!

[58] Roger Blench notes that the Gurage languages are highly divergent and wonders whether they might not be a primary branch, reflecting an origin of Afroasiatic in or near Ethiopia.