Senescence

Aging has been defined as "a progressive deterioration of physiological function, an intrinsic age-related process of loss of viability and increase in vulnerability.

Dolly the sheep died young from a contagious lung disease, but data on an entire population of cloned individuals would be necessary to measure mortality rates and quantify aging.

[citation needed] The evolutionary theorist George Williams wrote, "It is remarkable that after a seemingly miraculous feat of morphogenesis, a complex metazoan should be unable to perform the much simpler task of merely maintaining what is already formed.

[12] Planarian flatworms have "apparently limitless telomere regenerative capacity fueled by a population of highly proliferative adult stem cells.

[17][additional citation(s) needed] Good theories would both explain past observations and predict the results of future experiments.

Williams suggested the following example: Perhaps a gene codes for calcium deposition in bones, which promotes juvenile survival and will therefore be favored by natural selection; however, this same gene promotes calcium deposition in the arteries, causing negative atherosclerotic effects in old age.

[1][21] The theory suggests that aging occurs due to a strategy in which an individual only invests in maintenance of the soma for as long as it has a realistic chance of survival.

[25] It posits that free radicals produced by dissolved oxygen, radiation, cellular respiration and other sources cause damage to the molecular machines in the cell and gradually wear them down.

Calorically restricted animals process as much, or more, calories per gram of body mass, as their ad libitum fed counterparts, yet exhibit substantially longer lifespans.

[29] In a 2007 analysis it was shown that, when modern statistical methods for correcting for the effects of body size and phylogeny are employed, metabolic rate does not correlate with longevity in mammals or birds.

[30] With respect to specific types of chemical damage caused by metabolism, it is suggested that damage to long-lived biopolymers, such as structural proteins or DNA, caused by ubiquitous chemical agents in the body such as oxygen and sugars, are in part responsible for aging.

[citation needed] Under normal aerobic conditions, approximately 4% of the oxygen metabolized by mitochondria is converted to superoxide ion, which can subsequently be converted to hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radical and eventually other reactive species including other peroxides and singlet oxygen, which can, in turn, generate free radicals capable of damaging structural proteins and DNA.

(In Wilson's disease, a hereditary defect that causes the body to retain copper, some of the symptoms resemble accelerated senescence.)

These processes termed oxidative stress are linked to the potential benefits of dietary polyphenol antioxidants, for example in coffee,[31] and tea.

Lipid peroxidation of the inner mitochondrial membrane reduces the electric potential and the ability to generate energy.

It is probably no accident that nearly all of the so-called "accelerated aging diseases" are due to defective DNA repair enzymes.

B. S. Haldane wondered why the dominant mutation that causes Huntington's disease remained in the population, and why natural selection had not eliminated it.

[46][47] "The force of natural selection weakens with increasing age—even in a theoretically immortal population, provided only that it is exposed to real hazards of mortality.

Age-independent hazards such as predation, disease, and accidents, called 'extrinsic mortality', mean that even a population with negligible senescence will have fewer individuals alive in older age groups.

However, achieving this goal requires overcoming numerous challenges and implementing additional validation steps.

[68][69] A number of genetic components of aging have been identified using model organisms, ranging from the simple budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to worms such as Caenorhabditis elegans and fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster).

[70] Individual cells, which are genetically identical, nonetheless can have substantially different responses to outside stimuli, and markedly different lifespans, indicating the epigenetic factors play an important role in gene expression and aging as well as genetic factors.

[73] This report suggests that DNA damage, not oxidative stress, is the cause of this form of accelerated aging.

A study indicates that aging may shift activity toward short genes or shorter transcript length and that this can be countered by interventions.

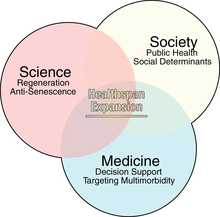

[74] Healthspan can broadly be defined as the period of one's life that one is healthy, such as free of significant diseases[76] or declines of capacities (e.g. of senses, muscle, endurance and cognition).

[76] Scientists have noted that "[c]hronic diseases of aging are increasing and are inflicting untold costs on human quality of life".

[81] Several researchers in the area, along with "life extensionists", "immortalists", or "longevists" (those who wish to achieve longer lives themselves), postulate that future breakthroughs in tissue rejuvenation, stem cells, regenerative medicine, molecular repair, gene therapy, pharmaceuticals, and organ replacement (such as with artificial organs or xenotransplantations) will eventually enable humans to have indefinite lifespans through complete rejuvenation to a healthy youthful condition (agerasia[82]).