Senghenydd colliery disaster

The inquest established that the colliery had high levels of airborne coal dust, which would have exacerbated the explosion and carried it further into the mine workings.

In October 2013, on the centenary of the tragedy, a Welsh national memorial to those killed in all Wales's mining disasters was unveiled at the former pithead, depicting a rescue worker coming to the aid of one of the survivors of the explosion.

[5] The South Wales Coalfield produced the sought-after anthracite, bituminous and steam coals—the latter a grade between the two comprising a hard coal without the coking elements.

[20] South Wales miners, including those at Universal, were paid on a rate determined by the Sliding Scale Committee, which fixed wages on the price coal fetched at market.

[25][26][e] When the price of coal slumped in the late 1890s, low wages led to industrial unrest and, in 1898, a strike that the men at Universal joined at the end of April.

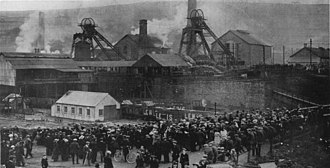

Because the explosion damaged the pit winding gear, it took time to clear the debris from the pithead to allow rescuers to begin work.

[35] The colliery had further problems in October 1910 when a heavy roof fall in the Mafeking return released trapped firedamp, which caused the mine to be temporarily evacuated.

[38][f] Among other changes to the health and safety culture, the act required that ventilation fans in all collieries be capable of reversing the air current underground; this measure was to be implemented by 1 January 1913.

[41] At 3:00 am on 14 October 1913, the day firemen descended the pit to conduct the daily checks for gas; they had three hours to complete their investigations.

The explosive wave travelled up the Lancaster shaft to the surface, destroying the headframe; it killed the winder—the man in charge—and badly injured his deputy.

[49][50] Edward Shaw, the colliery manager, was on the surface and the remaining shift foremen were still underground and unable to give assistance.

[54][55] Shaw and Thomas moved to the western side, where they found other men, alive but injured, and arranged for them to travel to the surface.

[57][58] From 11:00 am the specialist mines rescue teams began arriving at the colliery from the Rhymney and Rhondda Valleys, as did Red Cross workers and local ambulance services; a police detachment was sent from Cardiff in a special train.

[59][60][61] Lieven recounts how the rescue parties "in their desperation, ... were reckless with their lives" in their attempts to find survivors; many were injured in small roof collapses, or suffered the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning.

We talk in awed terms of the decimation of a regiment in a bloody battle, but here a great community engaged in the pursuit of a peaceful vocation is threatened with the loss of at least a quarter of its able bodied manhood".

[67] On the surface the townsfolk waited for news; a reporter for The Dundee Courier thought: "the scene at Senghenydd last night was depressing in the extreme.

[69][70] During the course of the day, 56 bodies were raised to the surface and, that evening, a new water supply, connected by three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) of pipes to a nearby reservoir, was installed in the Lancaster shaft.

[71] Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, visited the colliery on 15 October representing King George V, who was attending the marriage of Prince Arthur of Connaught and Princess Alexandra, 2nd Duchess of Fife.

[76][j] William Brace, the local MP speaking on behalf of the South Wales Miners' Federation, announced on 16 October that the priority would be given to putting out the fire and that no more search parties would be looking for survivors.

Progress in tackling the fire over the previous days had been slow, and it had only been extinguished in the first 30 yards of the roadway—still two miles (3.2 km) from the coal face.

[80][81] The fire was contained, but miners still faced several obstacles, including roof collapses and large pockets of trapped firedamp.

[87] The deaths of 440 men from a small community had a devastating effect; 60 victims were younger than 20, of whom 8 were 14 years old; 542 children had lost their fathers and 205 women were widowed.

[87][88] The inquiry into the disaster opened on 2 January 1914 with Richard Redmayne, the Chief Inspector of Mines, as the commissioner; he was assisted by two assessors, Evan Williams, the chairman of the South Wales and Monmouthshire Coal Owners Association, and Robert Smillie, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain.

[93][94] The report was critical of many aspects of the management's practices, and considered it had breached the mining regulations in respect of measuring and maintaining the air quality in the workings, and in the removal of coal dust from the tracks and walkways.

[95] The report pointed out that because the management had not implemented the changes needed to the ventilation fans as demanded by the Coal Mines Act 1911, the fans were unable to reverse the direction of the airflow, which would have blown the smoke out through the Lancaster shaft; Redmayne and his colleagues held differing opinions on the advisability of reversing or stopping the airflow.

[96][97] The historian John H Brown, in his examination of the disaster, states that had the airflow been reversed, firedamp or afterdamp could have been extracted from some sectors into the blaze, causing another explosion.

"[99] Shaw's actions were described by Lieven as those that "gained him a degree of respect from the local mining community which remained over the years; they probably also cost the lives of scores of miners.

[91][39] A stage play based on the disaster, by the journalist and broadcaster Margaret Coles, was first performed at the Sherman Cymru, Cardiff in 1991.

[107] The disaster at Senghenydd has provided the backdrop to two printed works of historical fiction: Alexander Cordell's This Sweet and Bitter Earth (1977)[108] and Cwmwl dros y Cwm (2013) by Gareth F.