Separation of powers

[1] To put this model into practice, government is divided into structurally independent branches to perform various functions[2] (most often a legislature, a judiciary and an administration, sometimes known as the trias politica).

It was Polybius who described and explained the system of checks and balances in detail, crediting Lycurgus of Sparta with the first government of this kind.

Calvin appreciated the advantages of democracy, stating: "It is an invaluable gift if God allows a people to elect its own government and magistrates.

[6][need quotation to verify] In 1620 a group of English separatist Congregationalists and Anglicans (later known as the Pilgrim Fathers) founded Plymouth Colony in North America.

[7] Massachusetts Bay Colony (founded 1628), Rhode Island (1636), Connecticut (1636), New Jersey, and Pennsylvania had similar constitutions – they all separated political powers.

John Locke (1632–1704) deduced from a study of the English constitutional system the advantages of dividing political power into the legislative (which should be distributed among several bodies, for example, the House of Lords and the House of Commons), on the one hand, and the executive and federative power, responsible for the protection of the country and prerogative of the monarch, on the other hand, as the Kingdom of England had no written constitution.

One of the first documents proposing a tripartite system of separation of powers was the Instrument of Government, written by the English general John Lambert in 1653, and soon adopted as the constitution of England for few years during The Protectorate.

[12][verification needed] An earlier forerunner to Montesquieu's tripartite system was articulated by John Locke in his work Two Treatises of Government (1690).

[14] Within these factors Locke heavily argues for "Autry for Action" as the scope and intensity of these campaigns are extremely limited in their ability to form concentrations of power.

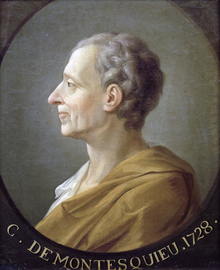

[18][19][20] In the British constitutional system, Montesquieu discerned a separation of powers among the monarch, Parliament, and the courts of law.

By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies, establishes public security, and provides against invasions.

There would be an end to everything, were the same man or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, executing the public resolutions, and trying the causes of individuals.

Immanuel Kant was an advocate of this, noting that "the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils" so long as they possess an appropriate constitution to pit opposing factions against each other.

A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control of the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public.

We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other and that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights.

[32] There are analytical theories that provide a conceptual lens through which to understand the separation of powers as realized in real-world governments (developed by the academic discipline of comparative government); there are also normative theories,[33] both of political philosophy and constitutional law, meant to propose a reasoned (not conventional or arbitrary) way to separate powers.

The executive function of government includes many exercises of powers in fact, whether in carrying into effect legal decisions or affecting the real world on its own initiative.