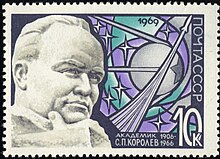

Sergei Korolev

Arrested on a false official charge as a "member of an anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary organization" (which would later be reduced to "saboteur of military technology"), he was imprisoned in 1938 for almost six years, including a few months in a Kolyma labour camp.

Before his death he was officially identified only as glavny konstruktor (главный конструктор), or the Chief Designer, to protect him from possible Cold War assassination attempts by the United States.

[3] Only following his death in 1966 was his identity revealed, and he received the appropriate public recognition as the driving force behind Soviet accomplishments in space exploration during and following the International Geophysical Year.

Local schools were closed and young Korolev had to continue his studies at home, where he suffered from a bout of typhus during the severe food shortages of 1919.

He continued courses at Kiev until he was accepted into the Bauman Moscow State Technical University (MVTU, BMSTU) in July 1926, having the famous aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev as his mentor, who was a professor there.

In 1931, Korolev and space travel enthusiast Friedrich Zander participated in the creation of the Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD), one of the earliest state-sponsored centers for rocket development in the USSR.

Joseph Stalin's Great Purge severely damaged RNII, with Director Kleymyonov and Chief Engineer Langemak arrested in November 1937, tortured, made to sign false confessions and executed in January 1938.

Many of the leading German rocket scientists, including Dr. von Braun himself, surrendered to Americans and were transported to the United States as part of Operation Paperclip.

NII-88 also incorporated 170+ German specialists – including Helmut Gröttrup and Fritz Karl Preikschat – with approximately half based at Branch 1 of NII-88 on Gorodomlya Island in Lake Seliger some 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Moscow.

Due to political and security concerns, German specialists were not allowed knowledge or access to any Soviet missile design[43] and in December 1948 work on the G-1 proposal was terminated.

Korolev joined the Soviet Communist Party that year to request money from the government for future projects including the R-5, with a more modest 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) range.

This was a two-stage rocket with a maximum payload of 5.4 tons, sufficient to carry the Soviets' bulky nuclear bomb an impressive distance of 7,000 kilometres (4,300 mi).

[22] On 26 May 1954, six days after being tasked to lead the R-7 ballistic missile program, Korolev submitted a proposal to use the R-7 to launch a satellite into space, naming a technical report from Tikhonravov and mentioning similar work being carried out by Americans.

[22] To intensify his lobbying efforts, Korolev, along with other like-minded engineers, began writing speculative articles for Soviet newspapers on space flight.

[22] While the US government debated the idea of spending millions of dollars on this concept, Korolev suggested the international prestige of launching a satellite before the United States.

The satellite was a simple polished metal sphere no bigger than a beach ball, containing batteries that powered a transmitter using four external communication antennas.

Nikita Khrushchev—initially bored with the idea of another Korolev rocket launch—was pleased with this success after the wide recognition, and encouraged launch of a more sophisticated satellite less than a month later, in time for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution on 3 November.

[21] Korolev and close associate Mstislav Keldysh wished to up the ante of building a second, larger satellite by proposing the idea of putting a dog on board, which sufficiently caught the interest of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

[21] Korolev's group was also working on ambitious programs for missions to Mars and Venus, putting a man in orbit, launching communication, spy and weather satellites, and making a soft-landing on the Moon.

After gaining approval from the government, a modified version of Korolev's R-7 was used to launch Yuri Alexeevich Gagarin into orbit on 12 April 1961, which was before the United States was able to put Alan Shepard into space.

[4] Long before we met him, one man dominated much of our conversation in the early days of our training; Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the mastermind behind the Soviet space program.

He glanced down a list of our names and called on us in alphabetical order to introduce ourselves briefly and talk about our flying careers.On August 11, 1962, Korolyov launched the first group flight with Vostok 3 and 4 (with Andriyan Nikolayev and Pavel Popovich).

After one uncrewed test flight, this spacecraft carried a crew of three cosmonauts, Komarov, Yegorov and Feoktistov, into space on 12 October 1964 and completed sixteen orbits.

In the meantime the change of Soviet leadership with the fall of Khrushchev meant that Korolev was back in favor and given charge of beating the US to landing a man on the Moon.

Korolev became convinced that Khrushchev was only interested in the space program for its propaganda value and feared that he would cancel it entirely if the Soviets started losing their leadership to the United States, so he continued to push himself.

It was stated by the government that he had what turned out to be a large, cancerous tumor in his abdomen, but Valentin Glushko later reported that he actually died due to a poorly performed operation for hemorrhoids.

The Soviet émigré Leonid Vladimirov related the following description of Korolev by Valentin Glushko at about this time: Short of stature, heavily built, with head sitting awkwardly on his body, with brown eyes glistening with intelligence, he was a skeptic, a cynic and a pessimist who took the gloomiest view of the future.

'We are all going to be shot and there will be no obituary' (Khlopnut bez nekrologa, Хлопнут без некролога – i.e. "we will all vanish without a trace") was his favorite expression.Korolev was rarely known to drink alcoholic beverages, and chose to live a fairly austere lifestyle.

Vincentini was heavily occupied with her own career, and about this time Korolev had an affair with a younger woman named Nina Ivanovna Kotenkova, who was an English interpreter in the Podlipki office.

Sergei Khrushchev claimed that his father Nikita rejected a Nobel Prize for Korolev out of concern that the award would anger the rest of the Council of Chief Designers.