Sestina

In fair Provence, the land of lute and rose, Arnaut, great master of the lore of love, First wrought sestines to win his lady's heart, For she was deaf when simpler staves he sang, And for her sake he broke the bonds of rhyme, And in this subtler measure hid his woe.

The oldest-known sestina is "Lo ferm voler qu'el cor m'intra", written around 1200 by Arnaut Daniel, a troubadour of Aquitanian origin; he refers to it as "cledisat", meaning, more or less, "interlock".

These early sestinas were written in Old Occitan; the form started spilling into Italian with Dante in the 13th century; by the 15th, it was used in Portuguese by Luís de Camões.

[5][6] The involvement of Dante and Petrarch in establishing the sestina form,[7] together with the contributions of others in the country, account for its classification as an Italian verse form—despite not originating there.

[9] Pontus de Tyard was the first poet to attempt the form in French, and the only one to do so prior to the 19th century; he introduced a partial rhyme scheme into his sestina.

[10] An early version of the sestina in Middle English is the "Hymn to Venus" by Elizabeth Woodville (1437–1492); it is an "elaboration" on the form, found in one single manuscript.

[13] The first appearance of the sestina in English print is "Ye wastefull woodes", comprising lines 151–89 of the August Æglogue in Edmund Spenser's Shepherd's Calendar, published in 1579.

In this variant the standard end-word pattern is repeated for twelve stanzas, ending with a three-line envoi, resulting in a poem of 75 lines.

Like "Ye Goatherd Gods" it is written in unrhymed iambic pentameter and uses exclusively feminine endings, reflecting the Italian endecasillabo.

"[18] In the 1870s, there was a revival of interest in French forms, led by Andrew Lang, Austin Dobson, Edmund Gosse, W. E. Henley, John Payne, and others.

[23][24][25] "Histoire" by Harry Mathews adds an additional Oulipian constraint: the end words wildly misusing ideological or prejudicial terms.

[7] Since then, changes to the line length have been a relatively common variant,[35] such that Stephanie Burt has written: "sestinas, as the form exists today, [do not] require expertise with inherited meter ...".

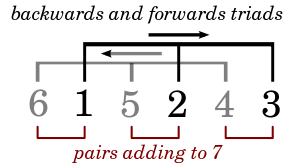

[37][page needed] This genetic hypothesis is supported by the fact that Arnaut Daniel was a strong dice player and various images related to this game are present in his poetic texts.

Stephanie Burt notes that, "The sestina has served, historically, as a complaint", its harsh demands acting as "signs for deprivation or duress".

[48] She believes that the aesthetic tension, which results from the "conception of its mathematical completeness and perfection", set against the "experiences of its labyrinthine complexities" can be resolved in the apprehension of the "harmony of the whole".