Sex worker

[7][8][9] The term "sex worker" has since spread into much wider use, including in academic publications, by NGOs and labor unions, and by governmental and intergovernmental agencies, such as the World Health Organization.

In addition, choosing to use the term "sex worker" rather than "prostitute" shows ownership over the individuals' career choices.

[12][13] Such groups view prostitution variously as a crime or as victimization, and see the term "sex work" as legitimizing criminal activity or exploitation as a type of labor.

[19] The motives of sex workers vary widely and can include debt, coercion, survival, or simply as a way to earn a living.

However, for many other motivations, such as stress reduction, self-esteem boost, emotional expression, or utilitarian reasons, there were no significant differences in frequency of engagement with real-life versus virtual partners.

[23] These motives also align with varying climates surrounding sex work in different communities and cultures.

In addition, finding a representative sample of sex workers in a given city can be nearly impossible because the size of the population itself is unknown.

Maintaining privacy and confidentiality in research is also difficult because many sex workers may face prosecution and other consequences if their identities are revealed.

[19] Globally, sex workers encounter barriers in accessing health care, legislation, legal resources, and labor rights.

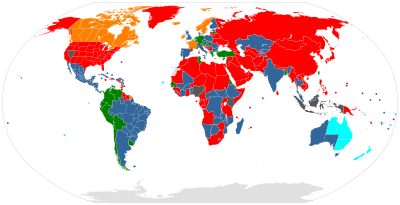

[35] Depending on local law, sex workers' activities may be regulated, controlled, tolerated, or prohibited.

Under the Prostitution Reform Act of New Zealand, laws and regulations have been put into place in order to ensure the safety and protection of its sex workers.

For example, since the implementation of the Prostitution Reform Act, "any person seeking to open a larger brothel, where more than four sex workers will be working requires a Brothel Operators Certificate, which certifies them as a suitable person to exercise control over sex workers in the workplace.

They answered that they thought it should not, as it would put women at higher risk from violent customers if it were considered legitimate work, and they would not want their friends or family entering the sex industry to earn money.

[citation needed] Another argument is that legalizing sex work would increase the demand for it, and women should not be treated as sexual merchandise.

[49] The criminalization of sex work in many places can also lead to a reluctance to disclose for fear of being turned in for illegal activities.

Personal factors include mental health issues that lead to increased sexual risk, such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse provoked through lack of support, violence, etc.

Structural risks include involvement in sex work being linked to poverty, substance abuse, and other factors that are more prevalent in transgender women based on their tendency to be socially marginalized and not accepted for challenging gender norms.

Othering involves constructing oneself as superior to one's peers, and the dancer persona provides an internal boundary that separates the "authentic" from the stripper self.

This practice creates a significant amount of stress for the dancers, in turn leading many to resort to using drugs and alcohol to cope.

This is because strippers concurrently attribute a strong moral constitution to those that resist the drug atmosphere; it is a testament to personal strength and willpower.

Further, the stress of trying to hide their lifestyles from others due to fear of scrutiny affects the mental health of dancers.

[50][56] Forced sex work often involves deception - workers are told that they can make a living and are then not allowed to leave.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, sex worker advocacy dates back to the late 19th century in Havana, Cuba.

The first organization within the contemporary sex workers' rights movement was Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE), founded in 1973 in San Francisco, California.

[61] Many regions are home to sex worker unions, including Latin America, Brazil, Canada, Europe, and Africa.

[60] Performers in general are problematic to categorize because they often exercise a high level of control over their work product, one characteristic of an independent contractor.

Some of the working conditions they were able to address included "protest[ing] racist hiring practices, customers being allowed to videotape dancers without their consent via one-way mirrors, inconsistent disciplinary policies, lack of health benefits, and an overall dearth of job security".

Unionizing exotic dancers can certainly bring better work conditions and fair pay, but it is difficult to do at times because of their dubious employee categorization.

[63][64] NGOs often play a large role in outreach to sex workers, particularly in HIV and STI prevention efforts.

[66] This lack of organization may be due to the legal status of prostitution and other sex work in the country in question; in China, many sex work and drug abuse NGOs do not formally register with the government and thus run many of their programs on a small scale and discreetly.