Shabbat candles

[2] Candle-lighting is traditionally done by the woman of the household,[3] but every Jew is obligated to either light or ensure that candles are lit on their behalf.

[9] One early-modern Yiddish prayer asks for the candles to "burn bright and clear to drive away the evil spirits, demons, and all that come from Lilith".

[8] Persius (d. 62 CE) describes it in Satire V:At cum Herodis venere dies unctaque fenestra dispositae pinguem nebulam vomuere lucaernae portantes violas .

"[13] Maimonides, who rejects Talmudic rationales based on superstition,[14] writes only: "And women are more obligated in this matter than men, because they are found at home[c] and involved in housework.

[21] Starting with Yaakov Levi Moelin, rabbinic authorities have required women who forgot to light one week to add an additional lamp to her regular number for the rest of her life.

[22] A recent custom reinterprets the two candles as husband and wife[d] and adds a new candle for every child born; apparently the first to hear of it was Israel Hayyim Friedman, though his essay was not published until 1965,[23] followed by Jacob Zallel Lauterbach, who mentions it in an undated essay published posthumously in 1951.

[25] Menashe Klein offers two interpretations: either it is based on Moelin's rule and women who miss a week because they were giving birth are not exempted (though all other authorities assume they are exempted) or it is based on comparison with Hanukkah candles, which some medieval authorities recommended be lit one per member of the household.

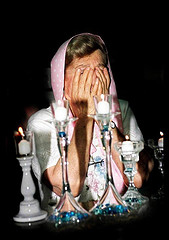

In order to avoid benefiting from the light of the candles before uttering the blessing, Ashkenazic authorities recommend that the lighter cover her eyes for the intervening period.

[27] Today, many Jewish women make an exaggerated motion, waving their hands in the air, when covering their eyes; there is no specific source for this in traditional texts.

The blessing is never described by Talmudic sources, but was introduced by Geonim to emphasize rejection of the early Karaitic belief that lights could not be lit before the Sabbath.

At least two earlier sources include this version, the Givat Shaul of Saul Abdullah Joseph (Hong Kong, 1906)[30] and the Yafeh laLev of Rahamim Nissim Palacci (Turkey, 1906)[31] but authorities in the major Orthodox traditions were solicited for responsa only in the late 1960s, and each acknowledges it only as a new and alternative practice.

Menachem Mendel Schneerson and Moshe Sternbuch endorsed the innovation[32] but most authorities, including Yitzhak Yosef, ruled that it is forbidden, though it does not nullify the blessing if already performed.