Tahmasp I

His reign saw a shift in the Safavid ideological policy; he ended the worshipping of his father as the Messiah by the Turkoman Qizilbash tribes and instead established a public image of a pious and orthodox Shia king.

He started a long process followed by his successors to end the Qizilbash influence on Safavid politics, replacing them with the newly introduced 'third force' containing Islamized Georgians and Armenians.

[5] Tahmasp's father, Ismail I (r. 1501–1524), who inherited the leadership the Safavid order from his brother, Ali Mirza, became shah of Iran in 1501, a state mired in civil war after the collapse of the Timurid Empire.

He conquered the territories of the Aq Qoyunlu tribal confederation, the lands of the Chinggisid[7] (Descendant of Genghis Khan) Uzbek Shaybanid dynasty in the eastern Iran, and many city-states by 1512.

Ismail defeated and killed Muhammad Shaybani in the Battle of Marv in 1510, returning Khorasan to Iranian possession, though Khwarazm and the Persianate cities in Transoxiana remained in Uzbek hands.

[19] Abu'l-Fath Tahmasp Mirza[20][a] was born on 22 February 1514 in Shahabad, a village near Isfahan, as the eldest son of Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum.

[29] Placing Tahmasp in Herat was an attempt to reduce the growing influence of the Shamlu tribe, which dominated Safavid court politics and held a number of powerful governorships.

Amir Soltan arrested Ghiyath al-Din and executed him the following day, but was ousted from his position in 1521 by a sudden raid by the Uzbeks who crossed the Amu Darya and seized portions of the city.

Its events however are difficult to reconstruct; on an unknown date, an agent from the Shamlu tribe unsuccessfully tried to poison Tahmasp; they revolted against the shah, who had recently asserted his authority by removing Hossein Khan.

[55] The Ottoman sultan launched his last campaign against the Safavids in May 1554, when Ismail Mirza (Tahmasp's son) invaded eastern Anatolia and defeated Erzerum governor Iskandar Pasha.

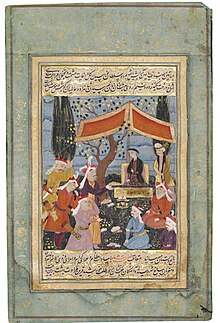

[68] Tahmasp honoured Homayun as a guest and gave him an illustrated version of Saadi's Gulistan dating back to the reign of Abu Sa'id Mirza (r. 1451–1469, 1459–1469), Humayun's great-grandfather;[69][70] however, he refused to give him political assistance unless he converted to Shia Islam.

[68][71] Humayun spent Nowruz in the Shah's court and left in 1545 with an army provided by Tahmasp to regain his lost lands; his first conquest was Kandahar, which he ceded to the young Safavid prince.

[72] Morad Mirza soon died, however, and the city became a bone of contention between the two empires: the Safavids claimed that it had been given to them in perpetuity, while the Mughals maintained that it had been an appanage that expired with the death of the prince.

According to Tarikh-e Alam-ara-ye Abbasi, "He unwisely sought recognition of his superior status vis-à-vis the other physicians; as a result, when Tahmasp died, Abu Nasr was accused of treachery in the treatment he had prescribed, and he was put to death within the palace by members of the qurchi".

The key change was the 1535 appointment of Qazi Jahan Qazvini, who extended diplomacy beyond Iran by establishing contact with the Portuguese, the Venetians, the Mughals, and the Shiite Deccan sultanates.

[87] Moving into a city that linked the realm to Khorasan through an ancient route, allowed a greater degree of centralisation as distant provinces such as Shirvan, Georgia, and Gilan were brought into the Safavid fold.

[92] On the shah's behalf, Abdi Beg Shirazi, a secretary-accountant in the royal chancellery, wrote a world history named Takmelat al-akhbar, which he dedicated it to Pari Khan Khanum, Tahmasp's daughter.

[93] He also commissioned Abol-Fath Hosseini to rewrite Safvat as-safa, the oldest surviving text regarding Safi-ad-din Ardabili and the Sufi beliefs of the Safavids, in order to legitimise his sayyid claim.

A court chronicle's retelling of Battle of Jam and a military review in 1530 show that the Safavid army was armed with several hundred light canons and several thousand infantrymen.

[22] Until 1533, the Qizilbash leaders (worshipping Ismail I as the promised Mahdi) urged the young Tahmasp to continue in his father's footsteps; that year, he had a spiritual rebirth, performed an act of repentance and outlawed irreligious behaviour.

[99] Tahmasp rejected his father's claim of being a mahdi, becoming a mystical lover of Ali and a king bound to sharia,[100] but still enjoyed villagers travelling to his palace in Qazvin to touch his clothing.

[105] Tahmasp saw Twelverism as a new doctrine of kingship, giving the ulama authority in religious and legal matters, and appointing Shaykh Ali al-Karaki as the deputy of the Hidden Imam.

[98] This brought new political and court power to the mullahs (Islamic clerics), sayyids, and their networks, intersecting Tabriz, Qazvin, Isfahan, and the recently incorporated centres of Rasht, Astarabad, and Amol.

[108] Tahmasp embarked on a wide-scale urban program designed to reinvent the city of Qazvin as a centre of Shiite piety and orthodoxy, expanding the Shrine of Husayn (son of Ali al-Rida, the eighth Imam).

[114] He encouraged painters such as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād,[115] bestowing a royal painting workshop for masters, journeymen, and apprentices with exotic materials such as ground gold and lapis lazuli.

[22][125] Other poets such as Naziri Nishapuri and 'Orfi Shirazi chose to leave Iran and emigrate to the Mughal court, where they pioneered the rise of Indian-style poetry (Sabk-i Hindi), known for its high-rhetorical texts of metaphors, mystical-philosophical themes and allegories.

[134] His only Turkoman consort was his chief wife, Sultanum Begum of the Mawsillu tribe (a marriage of state), who gave birth to two sons: Mohammad Khodabanda and Ismail II.

[134] However, he was attentive to his other children; On his orders, his daughters were instructed in administration, art, and scholarship,[136] and Haydar Mirza (his favourite son, born of a Georgian slave) participated in state affairs.

Eventually, Tahmasp did overcome that challenge; he proved himself a worthy military commander in the Battle of Jam against the Uzbeks and, instead of facing the Ottomans directly in the battlefield, he preferred to loot their rearguards.

[150] Tahmasp knew that he could not replace his father as a charismatic spiritual leader, and while he struggled to restore his family's legitimacy amongst the Qizilbash, he also had to craft a public figure of himself to convince the wider population of his right to rule as the new Safavid shah.