Shaivism

One of the largest Hindu denominations,[4][5] it incorporates many sub-traditions ranging from devotional dualistic theism such as Shaiva Siddhanta to yoga-orientated monistic non-theism such as Kashmiri Shaivism.

[2] It arrived in Southeast Asia shortly thereafter, leading to the construction of thousands of Shaiva temples on the islands of Indonesia as well as Cambodia and Vietnam, co-evolving with Buddhism in these regions.

[20] The term Shiva also connotes "liberation, final emancipation" and "the auspicious one", this adjective sense of usage is addressed to many deities in Vedic layers of literature.

It has no ecclesiastical order, no unquestionable religious authorities, no governing body, no prophet(s) nor any binding holy book; Hindus can choose to be polytheistic, pantheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic, or humanist.

Patanjali, while explaining Panini's rules of grammar, states that this term refers to a devotee clad in animal skins and carrying an ayah sulikah (iron spear, trident lance)[53] as an icon representing his god.

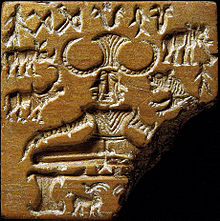

[62] Other evidence that is possibly linked to the importance of Shaivism in ancient times are in epigraphy and numismatics, such as in the form of prominent Shiva-like reliefs on Kushan Empire era gold coins.

According to Flood, coins dated to the ancient Greek, Saka and Parthian kings who ruled parts of the Indian subcontinent after the arrival of Alexander the Great also show Shiva iconography; however, this evidence is weak and subject to competing inferences.

[66][67] But following the Huna invasions, especially those of the Alchon Huns circa 500 CE, the Gupta Empire declined and fragmented, ultimately collapsing completely, with the effect of discrediting Vaishnavism, the religion it had been so ardently promoting.

[68] The newly arising regional powers in central and northern India, such as the Aulikaras, the Maukharis, the Maitrakas, the Kalacuris or the Vardhanas preferred adopting Shaivism instead, giving a strong impetus to the development of the worship of Shiva.

[73] Shaivism was the predominant tradition in South India, co-existing with Buddhism and Jainism, before the Vaishnava Alvars launched the Bhakti movement in the 7th century, and influential Vedanta scholars such as Ramanuja developed a philosophical and organizational framework that helped Vaishnavism expand.

[76] The region was also the source of Hindu arts, temple architecture, and merchants who helped spread Shaivism into southeast Asia in early 1st millennium CE.

[86][note 3] The epigraphical and cave arts evidence suggest that Shaiva Mahesvara and Mahayana Buddhism had arrived in Indo-China region in the Funan period, that is in the first half of the 1st millennium CE.

[90] In the centuries that followed, the merchants and monks who arrived in Southeast Asia, brought Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Buddhism, and these developed into a syncretic, mutually supporting form of traditions.

These traditions compare with Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism as follows: Shaiva manuscripts that have survived(post-8th century) Nepal and Himalayan region = 140,000 South India = 8,600 Others (Devanagiri) = 2,000 Bali and SE Asia = Many Over its history, Shaivism has been nurtured by numerous texts ranging from scriptures to theological treatises.

[163][164] Sanderson presents the historic classification found in Indian texts,[165] namely Atimarga of the Shaiva monks and Mantramarga that was followed by both the renunciates (sannyasi) and householders (grihastha) in Shaivism.

[182] The Lakula Shaiva ascetic recognized no act nor words as forbidden, he freely did whatever he felt like, much like the classical depiction of his deity Rudra in ancient Hindu texts.

Unlike Shankara's Advaita, Shaivism monist schools consider Maya as Shakti, or energy and creative primordial power that explains and propels the existential diversity.

The tradition teaches ethical living, service to the community and through one's work, loving worship, yoga practice and discipline, continuous learning and self-knowledge as means for liberating the individual Self from bondage.

[222] More broadly, the tantric sub-traditions sought nondual knowledge and enlightening liberation by abandoning all rituals, and with the help of reasoning (yuktih), scriptures (sastras) and the initiating Guru.

[237] The Nath consider Shiva as "Adinatha" or the first guru, and it has been a small but notable and influential movement in India whose devotees were called "Yogi" or "Jogi", given their monastic unconventional ways and emphasis on Yoga.

[237] They combined both theistic practices such as worshipping goddesses and their historic Gurus in temples, as well monistic goals of achieving liberation or jivan-mukti while alive, by reaching the perfect (siddha) state of realizing oneness of self and everything with Shiva.

Similarly, Shakta Hindus revere Shiva and goddesses such as Parvati, Durga, Radha, Sita and Saraswati important in Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions.

Shaivism was highly influential in southeast Asia from the late 6th century onwards, particularly the Khmer and Cham kingdoms of Indochina, and across the major islands of Indonesia such as Sumatra, Java and Bali.

Bhattara Guru's wife in southeast Asia is the same Hindu deity Durga, who has been popular since ancient times, and she too has a complex character with benevolent and fierce manifestations, each visualized with different names such as Uma, Sri, Kali and others.

[276] The Smartas are associated with the Advaita Vedanta theology, and their practices include the Panchayatana puja, a ritual that incorporates simultaneous reverence for five deities: Shiva, Vishnu, Surya, Devi and Ganesha.

[298][299][300] This is celebrated in Shaiva temples as Nataraja, which typically shows Shiva dancing in one of the poses in the ancient Hindu text on performance arts called the Natya Shastra.

In southeast Asia, the two traditions were not presented in competitive or polemical terms, rather as two alternate paths that lead to the same goals of liberation, with theologians disagreeing which of these is faster and simpler.

[90][319][320] Jainism co-existed with Shaiva culture since ancient times, particularly in western and southern India where it received royal support from Hindu kings of the Chaulukya, Ganga and Rashtrakuta dynasties.

[325] Shaiva Puranas, Agamas and other regional literature refer to temples by various terms such as Mandir, Shivayatana, Shivalaya, Shambhunatha, Jyotirlingam, Shristhala, Chattraka, Bhavaggana, Bhuvaneshvara, Goputika, Harayatana, Kailasha, Mahadevagriha, Saudhala and others.

[337] Other texts mention five Kedras (Kedarnatha, Tunganatha, Rudranatha, Madhyamesvara and Kalpeshvara), five Badri (Badrinatha, Pandukeshvara, Sujnanien, Anni matha and Urghava), snow lingam of Amarnatha, flame of Jwalamukhi, all of the Narmada River, and others.