Shale oil extraction

In the 10th century, the Assyrian physician Masawaih al-Mardini (Mesue the Younger) wrote of his experiments in extracting oil from "some kind of bituminous shale".

[3] China (Manchuria), Estonia, New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland began extracting shale oil in the early 20th century.

[8] Australia, the US, and Canada have tested shale oil extraction techniques via demonstration projects and are planning commercial implementation; Morocco and Jordan have announced their intent to do the same.

[21][24] The composition of the oil shale may lend added value to the extraction process through the recovery of by-products, including ammonia, sulfur, aromatic compounds, pitch, asphalt, and waxes.

[13] Heating the oil shale to pyrolysis temperature and completing the endothermic kerogen decomposition reactions require a source of energy.

Some technologies burn other fossil fuels such as natural gas, oil, or coal to generate this heat and experimental methods have used electricity, radio waves, microwaves, or reactive fluids for this purpose.

Temperatures below 600 °C (1,110 °F) are preferable, as this prevents the decomposition of limestone and dolomite in the rock and thereby limits carbon dioxide emissions and energy consumption.

Thermal dissolution involves the application of solvents at elevated temperatures and pressures, increasing oil output by cracking the dissolved organic matter.

By process principles: Based on the treatment of raw oil shale by heat and solvents the methods are classified as pyrolysis, hydrogenation, or thermal dissolution.

The voids enable a better flow of gases and fluids through the deposit, thereby increasing the volume and quality of the shale oil produced.

[13] Internal combustion technologies burn materials (typically char and oil shale gas) within a vertical shaft retort to supply heat for pyrolysis.

Uneven distribution of gas across the retort can result in blockages when hot spots cause particles to fuse or disintegrate.

[13][38] In addition to not accepting fine particles as feed, these technologies do not utilize the potential heat of combusting the char on the spent shale and thus must burn more valuable fuels.

[41] The Chattanooga process uses a fluidized bed reactor and an associated hydrogen-fired heater for oil shale thermal cracking and hydrogenation.

[45] John Fell experimented with in situ extraction, at Newnes, In Australia, during 1921, with some success,[46][47] but his ambitions were well ahead of technologies available at the time.

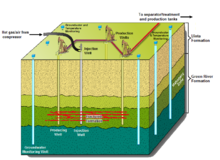

The first modified in situ oil shale experiment in the United States was conducted by Occidental Petroleum in 1972 at Logan Wash, Colorado.

[49] The processing area is isolated from surrounding groundwater by a freeze wall consisting of wells filled with a circulating super-chilled fluid.

[53] General Synfuels International has proposed the Omnishale process involving injection of super-heated air into the oil shale formation.

It injects an electrically conductive material such as calcined petroleum coke into the hydraulic fractures created in the oil shale formation which then forms a heating element.

The concept presumes a radio frequency at which the skin depth is many tens of meters, thereby overcoming the thermal diffusion times needed for conductive heating.

[2] Radio frequency processing in conjunction with critical fluids is being developed by Raytheon together with CF Technologies and tested by Schlumberger.

[72] Upgrading shale oil into transport fuels requires adjusting hydrogen–carbon ratios by adding hydrogen (hydrocracking) or removing carbon (coking).

According to the United States Department of Energy, the capital costs of a 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m3/d) ex-situ processing complex are $3–10 billion.

[76] The various attempts to develop oil shale deposits have succeeded only when the shale-oil production cost in a given region is lower than the price of petroleum or its other substitutes.

According to a survey conducted by the RAND Corporation, the cost of producing shale oil at a hypothetical surface retorting complex in the United States (comprising a mine, retorting plant, upgrading plant, supporting utilities, and spent oil shale reclamation), would be in a range of $70–95 per barrel ($440–600/m3), adjusted to 2005 values.

In addition, the atmospheric emissions from oil shale processing and combustion include carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

Environmentalists oppose production and usage of oil shale, as it creates even more greenhouse gases than conventional fossil fuels.

[92] Experimental in situ conversion processes and carbon capture and storage technologies may reduce some of these concerns in the future, but at the same time they may cause other problems, including groundwater pollution.

[29][96][97][98] A 2008 programmatic environmental impact statement issued by the US Bureau of Land Management stated that surface mining and retort operations produce 2 to 10 U.S. gallons (7.6 to 37.9 L; 1.7 to 8.3 imp gal) of waste water per 1 short ton (0.91 t) of processed oil shale.

In one result, Queensland Energy Resources put the proposed Stuart Oil Shale Project in Australia on hold in 2004.