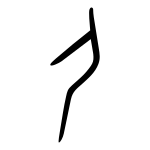

Shi (personator)

The word shi 尸 "corpse; personator; inactive; lay out; manage; spirit tablet" can be discussed in terms of Chinese character evolution, historical phonology, semantics, and English translations.

The oracle bone script for shi 尸 "corpse" was used interchangeably for yi 夷 "barbarian; non-Chinese people (esp.

Many characters written with this radical involve the body (e.g., niao 尿 "urine" with 水 "water"), but not all (e.g., wu 屋 "house; room" with 至 "go to").

Karlgren explains, "'The good men act the corpse,' play the part of a representative of the dead at a sacrifice, who sits still and silent during the whole ceremony; here then, remain inactive, do nothing to help."

Commentators disagree whether this shi means zhu, specifically muzhu 木主 "wooden spirit/ancestral tablet" or jiu "corpse in a coffin".

The sinologists Eduard Erkes and Bernhard Karlgren debated this Chuci usage of shi "corpse; spirit tablet".

Paul K. Benedict suggested possible Proto-Sino-Tibetan roots for shi: either *(s-)raw "corpse; carcass" or *siy "die".

[18] He rejects Karlgren's assumption that shi "corpse" is cognate to si "to die", "because the MC [Middle Chinese] initial ś- (< *lh-, *nh-, *hj-) never derives from an *s-, except when they share an initial *l or *n." English translations of the ceremonial shi 尸 include personator, impersonator, representative, medium, and shaman.

Medium and shaman are similar with shi in meaning and are part of Chinese traditions; however, the descriptions of a dignified personator are unlike the spirit-possession of either.

Lothar von Falkenhausen contrasts the frequently recorded shi "personator" with the rarely noted wu 巫 "shaman; spirit medium".

Occupying their ritual rôle by virtue of their kinship position vis-à-vis the ancestor that is sacrificed to, the Impersonators are not trained religious specialists like the Spirit Mediums.

Although it has been speculated that the actions of the shi may have originally involved trance and possession, the surviving source materials—none earlier than the Western Zhou period—show them as staid and passive, acting with the utmost demeanor and dignity.

One points to defeat because someone other than the chosen leader interferes with the command; the other is similar in its general meaning, but the expression, "carries corpses in the wagon," is interpreted differently.

On the basis of this custom the text is interpreted as meaning that a "corpse boy" is sitting in the wagon, or, in other words, that authority is not being exercised by the proper leaders but has been usurped by others.

Shijing odes 247 and 248, which portray ancestral feasts to the Zhou royal house, exclusively use the term gongshi 公尸 with the modifier gong 公 "prince; duke; public; palace; effort".

[27] Ode 247 (Jizui 既醉 "Already Drunk") describes a sacrificial feast for ancestral spirits, and says "the representative of the (dead) princes makes a happy announcement".

Ode 248 (Fuyi 鳧鷖 "Wild Ducks") describes another feast, which commentators say was held on the following day to reward the personator, and details sacrificial offerings and ancestral blessings.

Besides the Shijing, other texts refer to shi frequently drinking sacrificial jiu 酒 "alcoholic beverage; liquor", which Paper interprets as a ritual means to induce hallucinations of ancestral spirits.

[28] Based upon a Liji ceremony[29] describing a shi personator drinking nine cups of jiu, with an estimated alcohol content from 5% to 8%, and volume measurements of Zhou bronze sacrificial cups, Paper calculates a "conservative estimate is that the shi consumed between 2.4 and 3.9 ounces of pure alcohol (equivalent to between 5 and 8 bar shots of eighty-proof liquor).

"[30] Several texts refer to a Chinese custom that a personator should be a child of the same sex as the dead ancestor, preferably either a legitimate grandson or his wife.

The earliest textual reference comes from the Mengzi ("Book of Mencius") questioning the status shown to a younger brother during the personation ceremony.

[35] Julian Jaynes mentions a Greek parallel: the philosopher Iamblichus wrote that "young and simple persons" make the most suitable mediums.

As in instances of mediumism around the world, the youthful and illiterate were regarded as more reliable conduits to the dead, since they could hardly be suspected of having fabricated their utterances and writings themselves.

Women and junior male members of a family frequently found that mediumism was a way to bring attention to their own, otherwise easily ignored, concerns.

"[43] The above Liji description of Zhou "subscription club" personation ceremonies quotes Confucius's student and compiler Zengzi (505–436 BCE).

The Han dynasty historian Ban Gu explains: The personator is found in the ceremony wherein sacrifice is offered to ancestors, because the soul emitting no perceptible sounds and having no visible form, the loving sentiment of filial piety finds no means of displaying itself, hence a personator has been chosen to whom meats are offered, after which he breaks the bowls, quite rejoiced, as if his own father had eaten plenty.

Carr[47] offers a contemporary explanation for shi "corpse" personation: Julian Jaynes's psychological bicameral mentality hypothesis.

Paper suggested the possibility that Shang and Zhou shi wore bronze masks "symbolizing the spirit of the dead to whom the sacrifices were offered".

[50] Liu believes the phantasmagoric bronze masks discovered at Sanxingdui, dating from c. 12th–11th centuries BCE, might have been ritually worn by shi 尸.

The shi was generally a close, young relative who wore a costume (possibly including a mask) reproducing the features of the dead person.