Sholes and Glidden typewriter

Principally designed by the American inventor Christopher Latham Sholes, it was developed with the assistance of fellow printer Samuel W. Soule and amateur mechanic Carlos S. Glidden.

Work began in 1867, but Soule left the enterprise shortly thereafter, replaced by James Densmore, who provided financial backing and the driving force behind the machine's continued development.

The machine incorporated elements which became fundamental to typewriter design, including a cylindrical platen and a four row QWERTY keyboard.

The new communication technologies and expanding businesses of the late 19th century, however, had created a need for expedient, legible correspondence, and so the Sholes and Glidden and its contemporaries soon became common office fixtures.

Carlos S. Glidden, an inventor who frequented the machine shop, became interested in the device and suggested that it might be adapted to print alphabetical characters as well.

[3] In July 1867, Glidden read an article in Scientific American describing "the Pterotype", a writing machine invented by John Pratt and recently featured in an issue of London Engineering.

[5][6] In November 1866, following their successful collaboration on the numbering machine,[4] Sholes asked Soule to join him and Glidden in developing the new device.

[8][9] Densmore saw the machine for the first time in March 1868, and was unimpressed; he thought it clumsy and impractical, and declared it "good for nothing except to show that its underlying principles were sound".

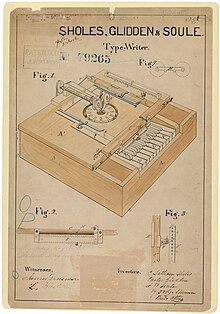

[11] A patent for the "Type-Writer" was granted on June 23, 1868, and, despite the device's flaws, Densmore rented a building in Chicago in which to begin its manufacture.

[15] Sholes adapted the idea and implemented a rotating drum to which the paper was clipped, replacing the frame of the previous model.

[16] Soule and Glidden did not assist development of the new platen and, as their interest in the venture was waning, sold their rights to the original machine to Sholes and Densmore.

Western Union ordered several machines,[20] but declined to purchase the rights, as it believed a superior device could be developed for less than Densmore's asking price of $50,000.

[28] Following a demonstration at Remington's offices in New York, the company contracted on March 1, 1873, to manufacture 1,000 machines, with the option to produce an additional 24,000.

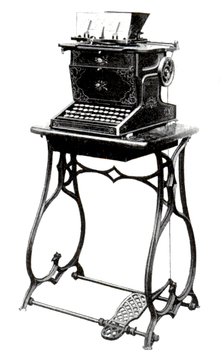

[28][29][g] Remington dedicated a wing of its factory to the typewriter, and spent several months retooling and re-engineering the device; production began in September and the machine entered the market on July 1, 1874.

Typewriter production was largely overseen by Jefferson Clough and William K. Jenne, manager of Remington's sewing machine division.

[36] The arrangement marked the beginning of the typewriter's commercial success,[41] as the agency's marketing prowess led to the sale of 1,200 machines in its first year.

[13] By the end of 1872, the appearance and function of the typewriter had assumed the form that would become standard in the industry and remain largely unchanged for the next century.

Although competing brands, such as the Oliver and Underwood, began to market "visible" typewriters in the 1890s, a Remington-branded model did not appear until the Remington No.

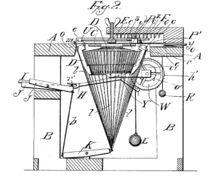

When a key was pressed, the corresponding typebar would swing upwards, causing the print head to strike at the center of the ring.

The implication of this design, however, was that pressing adjoining keys in quick succession would cause their typebars to collide and jam the machine.

[54] Individuals receiving typewritten letters often found them insulting (as type implied they could not read handwriting) or impersonal, problems exacerbated by the all upper-case writing.

[54][55] The typewriter also precipitated privacy concerns, as recipients of letters of a personal nature believed a third-party operator or typesetter must have been involved in their composition.

[57] Before the typewriter was acquired by Remington, Sholes' daughter was employed to demonstrate the device and to appear in promotional images, which served as the basis for early advertisements.

[58] Remington's sales agents later marketed the machine with tactics including the use of attractive women to demonstrate the device at trade shows and in hotel lobbies.

[59] The expansion of correspondence and paper work made possible by the efficiency of typewriters also created demand for additional clerical workers.

As typing and stenography positions could pay up to ten times more than those in factories, women began to be more attracted to office work.