Show Indians

Many veterans from the Great Plains Wars participated in Wild West shows,[1] during a time when the Office of Indian Affairs was intent on promoting Native assimilation.

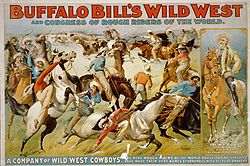

Originating with Buffalo Bill, between 1885 and 1898, the shows also re-enacted the Battle of the Little Bighorn and the death of George Armstrong Custer as well as the Wounded Knee Massacre after that incident in 1890.

[9] The performances provided Native Americans with an avenue to continue participating in cultural practices deemed illegal on Indian reservations.

"Perhaps they realized in the deepest sense, that even a caricature of their youth was preferable to a complete surrender to the homogenization that was overtaking American society," he wrote.

[10] The Wild West shows provided a space to be Indian and remain free of harassment from missionaries, teachers, agents, humanitarians, and politicians over the course of fifty years.

[12] Reformers insisted that the supposed savagery of Native Americans needed to undergo the effects of civilization through land ownership, education, and industry.

Rocky Bear began by pointing out that he long had served the interests of the federal government (Great White Father) by encouraging the development of Indian reservations.

Native American performers and their families were able to free themselves for six months each year from the degrading confines of government reservations where they were forbidden to wear tribal dress, hunt or dance.

Native American performers were treated well by Colonel Cody and received wages, food, transportation and living accommodation while far away from their homes.

Show Indians were allowed to wear traditional clothing then forbidden on the reservation, and lived in the Wild West's tipi "village", weather permitting, where visitors would stroll and meet performers.

74 Indians from Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, who had recently returned from a tour of Europe, were contracted to perform in the show.

Cody brought in an additional 100 Lakota from Pine Ridge, Standing Rock, and Rosebud reservations, who visited the fair at his expense and participated in the opening ceremonies.

[25][26] The popular perception of the Sioux as the distinctive American Indian first emerged with early dime novel writers, then the Wild West shows maintained that image and it persisted through film, radio, and television westerns.

Joy Kasson notes that "in a manner that has become familiar in the age of electronic popular culture, an entertainment spectacle was taken for 'the real thing,' and showmanship became inextricably entwined with its ostensible subject.

[citation needed] In 1898, Käsebier watched Buffalo Bill's Wild West troupe parade past her Fifth Avenue studio in New York City, toward Madison Square Garden.

[30] Her memories of affection and respect for the Lakota people inspired her to send a letter to William "Buffalo Bill" Cody requesting permission to photograph in her studio members of the Sioux tribe traveling with the show.

Käsebier's project was purely artistic and her images were not made for commercial purposes and never used in Buffalo Bill's Wild West program booklets or promotional posters.

Käsebier admired their efforts, but desired to, in her own words, photograph a "real raw Indian, the kind I used to see when I was a child", referring to her early years in Colorado and on the Great Plains.

The resulting photograph was exactly what Käsebier had envisioned: a relaxed, intimate, quiet, and beautiful portrait of the man, devoid of decoration and finery, presenting himself to her and the camera without barriers.

Chief Iron Tail was a superb showman and chaffed at the photo of him relaxed, but Käsebier chose it as the frontispiece for a 1901 Everybody’s Magazine article.

In 1898, Chief Flying Hawk was new to show business and unable to hide his anger and frustration imitating battle scenes from the Great Plains Wars for Buffalo Bill's Wild West to escape the constraints and poverty of the Indian reservation.

Iron Tail was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents.

Chief Iron Tail was an international personality and appeared as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs-Élysées in Paris, France and the Colosseum in Rome, Italy.

[37] On one of his visits to The Wigwam of Major Israel McCreight in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, Buffalo Bill asked Iron Tail to illustrate in pantomime how he played and won a game of poker with U. S. army officials during a Treaty Council in the old days.

Iron Tail continued to travel with Buffalo Bill until 1913, and then the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West until his death in 1916.

The London Courier reported Chief Blue Horse and companions were treated to an evening of English hospitality:"Willesden was as it were taken by storm on Sunday last, being invaded by the Indian contingent of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Jones, of the White Hart Hotel had, as another instance of his great geniality, invited Red Shirt, Blue Horse, Little Bull, Little Chief and Flies Above and about twenty others to an outing to his well-known hostelry, whereabout they might enjoy his bounteous hospitality.

Chief Blue Horse joined Colonel Cummins' Wild West Indian Congress and Rough Riders of the World and made public appearances at the Exposition.

McCowan of the Department of Anthropology replied to Chief Blue Horse that he had no use for him and that it was not the purpose of the government to expend money bringing large numbers of old Indians to the fair.

Their interpreter was Henry Standing Soldier, an educated man who had been a participant in the 1901 Pan American Exposition Wild West Show.