Śramaṇa

[13][14] According to Olivelle and Crangle, the earliest known explicit use of the term śramaṇa is found in section 2.7 of the Taittiriya Aranyaka, a layer within the Yajurveda (~1000 BCE, a scripture of Hinduism).

[17][18] The word śramaṇa is postulated to be derived from the verbal root śram, meaning "to exert effort, labor or to perform austerity".

Several śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy.

[32] Reginald Ray concurs that Śramaṇa movements already existed and were established traditions in pre-6th century BCE India, but disagrees with Wiltshire that they were nonsectarian before the arrival of Buddha.

[33][note 3] In the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16), a śramaṇa named Subhadda mentions: ...those ascetics, samaṇa and Brahmins who have orders and followings, who are teachers, well-known and famous as founders of schools, and popularly regarded as saints, like Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, Sanjaya Belatthiputta and Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta (Mahavira)...

Patrick Olivelle, a professor of Indology and known for his translations of major ancient Sanskrit works, states in his 1993 study that contrary to some representations, the original Śramaṇa tradition was a part of the Vedic one.

In all likelihood states Olivelle, during the Vedic era, neither did the Śramaṇa concept refer to an identifiable class, nor to ascetic groups as it does in later Indian literature.

[41] Rig Veda, for example, in Book 10 Chapter 136, mentions mendicants as those with kēśin (केशिन्, long-haired) and mala clothes (मल, dirty, soil-colored, yellow, orange, saffron) engaged in the affairs of mananat (mind, meditation).

[48][49] Pande attributes the origin of Buddhism, not entirely to the Buddha, but to a "great religious ferment" towards the end of the Vedic period when the Brahmanic and Sramanic traditions intermingled.

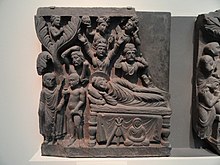

[60] Some scholars posit that the Indus Valley civilisation symbols may be related to later Jain statues, and the bull icon may have a connection to Rishabhanatha.

[66] Buddhism also developed a code for interaction of world-pursuing lay people and world-denying Buddhist monastic communities, which encouraged continued relationship between the two.

This code played a historic role in its growth, and provided a means for reliable alms (food, clothing) and social support for Buddhism.

[68][note 6] Ājīvika was founded in the 5th century BCE by Makkhali Gosala, as a śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early Buddhism and Jainism.

[55][71] Ancient texts of Buddhism and Jainism mention a city in the first millennium BCE named Savatthi (Sanskrit Śravasti) as the hub of the Ājīvikas; it was located in what is now the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

In later part of the common era, inscriptions suggests that the Ājīvikas had a significant presence in the South Indian state of Karnataka and the Kolar district of Tamil Nadu.

Ashokavadana also mentions that Bindusara's son Ashoka converted to Buddhism, became enraged at a picture that depicted Buddha in negative light, and issued an order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana.

[82]Another Jain canon, Sūtrakrtanga[83] describes the śramaṇa as an ascetic who has taken Mahavrata, the five great vows: He is a Śramaṇa for this reason that he is not hampered by any obstacles, that he is free from desires, (abstaining from) property, killing, telling lies, and sexual intercourse; (and from) wrath, pride, deceit, greed, love, and hate: thus giving up every passion that involves him in sin, (such as) killing of beings.

[88][89] This concept called Anatta (or Anatman) is a part of Three Marks of existence in Buddhist philosophy, the other two being Dukkha (suffering) and Anicca (impermanence).

[91] Ājīvikas were atheists[92] and rejected the epistemic authority of the Vedas, but they believed that in every living being there is an ātman – a central premise of Hinduism and Jainism as well.

[145] While the concepts of Brahman and Atman (Soul, Self) can be consistently traced back to pre-Upanishadic layers of Vedic literature, the heterogeneous nature of the Upanishads show infusions of both social and philosophical ideas, pointing to evolution of new doctrines, likely from the Sramanic movements.

[61] The Chāndogya Upaniṣad, dated to about the 7th century BCE, in verse 8.15.1, has the earliest evidence for the use of the word Ahimsa in the sense familiar in Hinduism (a code of conduct).

Doniger summarizes the historic interaction between scholars of Vedic Hinduism and Sramanic Buddhism: There was such constant interaction between Vedism and Buddhism in the early period that it is fruitless to attempt to sort out the earlier source of many doctrines, they lived in one another's pockets, like Picasso and Braque (who, in later years, were unable to say which of them had painted certain paintings from their earlier, shared period).

As Geoffrey Samuel notes, Our best evidence to date suggests that [yogic practice] developed in the same ascetic circles as the early śramaṇa movements (Buddhists, Jainas and Ajivikas), probably in around the sixth and fifth centuries BCE.

[154][note 10] Patrick Olivelle suggests that the Hindu ashrama system of life, created probably around the 4th-century BCE, was an attempt to institutionalize renunciation within the Brahmanical social structure.

Clement of Alexandria makes several mentions of the śramaṇas, both in the context of the Bactrians and the Indians: Thus philosophy, a thing of the highest utility, flourished in antiquity among the barbarians, shedding its light over the nations.

First in its ranks were the prophets of the Egyptians; and the Chaldeans among the Assyrians;[155] and the Druids among the Gauls; and the Samanaeans among the Bactrians ("Σαμαναίοι Βάκτρων"); and the philosophers of the Celts; and the Magi of the Persians, who foretold the Saviour's birth, and came into the land of Judaea guided by a star.

"[citation needed] For the polity of the Indians being distributed into many parts, there is one tribe among them of men divinely wise, whom the Greeks are accustomed to call Gymnosophists.

Having likewise the superfluities of his body cut off, he receives a garment, and departs to the Samanaeans, but does not return either to his wife or children, if he happens to have any, nor does he pay any attention to them, or think that they at all pertain to him.

[157]They are so disposed with respect to death, that they unwillingly endure the whole time of the present life, as a certain servitude to nature, and therefore they hasten to liberate their souls from the bodies [with which they are connected].

[157]German novelist Hermann Hesse, long interested in Eastern, especially Indian, spirituality, wrote Siddhartha, in which the main character becomes a Samana upon leaving his home.