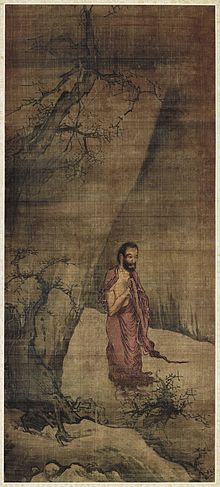

Shussan Shaka

Shussan Shaka (Japanese: 出山釈迦 shussan shaka; Chinese: 出山釋迦 chūshān shìjiā; English: Śākyamuni Descending from the Mountain)[1] is a subject in East Asian Buddhist art and poetry, in which Śākyamuni Buddha returns from six years of asceticism in the mountains, having realized that ascetic practice is not the path to enlightenment.

[4] So, a solitary Śākyamuni descended the mountain, left the life of extreme austerity behind him, and traveled instead to Gaya, the city that would become known as the famous site of his enlightenment under the bodhi tree.

[6] Shussan Shaka was popularized as a subject in painting in the thirteenth century during the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279),[7] the period during which Chan reached its height in China.

[2] In Japan, Shussan Shaka became particularly associated with the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism and saw more prolonged popularity as a painting subject than in China, even into the Edo Period.

[11] In Japan, unlike in China, this Zen painting motif was on rare occasions translated to other forms of art, such as print illustration and sculpture.

[4] Though part of a broader tradition in Buddhist art and literature across Asia of depicting Śākyamuni during his years of asceticism, the story of Shussan Shaka in particular is unique to Zen.

[3] Hence, according to Helmut Brinker and Hiroshi Kanazawa, the chief function of the motif of Shussan Shaka is to demonstrate "Śākyamuni's role as earthly religion founder.

"[3] For this reason, portrayals of Śākyamuni descending the mountain after asceticism generally call viewers' attention to the human frailty of this important figure, grounding him in the earthly as opposed to deifying him.

[2] Finally, the narrative of the story itself in conjunction with artists' emphasis on earthliness suggests, in accordance with Zen teaching, that enlightenment is not found by completely cutting off oneself from the world.

[2] In ritual use, Shussan Shaka paintings are hung on the walls of Rinzai Zen temples during the holiday celebrating the enlightenment of Śākyamuni Buddha.

[2] This practice suggests that Śākyamuni's years of asceticism and self-denial in the mountains are indeed tied to his enlightenment in the religious understanding of these Zen practitioners.

[4] In light of this reading, Śākyamuni's subsequent meditation and what is conventionally understood as his enlightenment under the bodhi tree at Gaya then also poses an interpretive challenge to scholars.

[2] For instance, according to Helmut Brinker, the following colophon by the Zen master Zhongfeng Mingben (1263–1323) suggests an interpretation of Shussan Shaka as an enlightened Buddha returning to the world to spread his wordless teaching: He who emerges from the mountains and has entered the mountains:That is originally You.If one calls him "You"It still is not he.The venerable master Shijia (Śākyamuni) comes.Ha, ha, ha...!

[2] Liang Kai was not a Zen monk painter, but after he abandoned his position at the Imperial Academy and turned to a lifestyle of heavy drinking, his portraits came to suggest influences of the Chan painting tradition.

[2] According to the analysis of Hiroshi Kanazawa, Liang Kai's Shakyamuni Descending the Mountain After Asceticism presents the viewer with an as yet unenlightened Śākyamuni.

[4] A member of the Southern Song literati who interacted closely with Chan priests, Li Que had in turn studied Liang Kai's later work, and was known for his spontaneous painting style.

"[7] The Cleveland Shussan Shaka bears an inscription attributed to the Zen priest Chijue Daochong, (1170–1251),[3] which reads: Since entering the mountain, too dried out and emaciatedFrosty cold over the snow,After having a twinkling of revelation with impassioned eyesWhy then do you want to come back to the world?In Brinker's view, Chijue Daocheng's poem exhibits an interpretation of this image as a portrait of the Buddha returning to society having already attained enlightenment, or "revelation," in the mountains.

[2] While the work overall appears very carefully composed and executed, the fine detail of Sakyamuni's face and body is juxtaposed with the less meticulous character of his robes.

[2] Xiyan Liaohui's inscription, brushed in the "running script" style and emulating the hand of Wuzhun Shifan, reads: At midnight he saw the morning star.In the mountains his cold words had increased.Before his feet emerged from the mountainsThese words were running through the world:"I see that all living [creatures] are completed into Buddhas since some time.There is only You, old fellow, who is still lacking complete Enlightenment.Helmut Brinker characterizes the tone of this colophon as "desperate" and "despairing," belying "frustration" and "discontent," presenting to the reader a Śākyamuni who has not yet reached his goal.

[2] Although the artist of the Choraku-ji Shussan Shaka is unknown, the style of the painting leads scholars to infer that the creator of this work was a Zen priest rather than a trained painter.

[2] Yet, Carla M. Zainie suggests that Huizhi's colophon remains open to interpretation due to the fact that "confused" could alternatively be taken to signify a kind of spiritual revelation.

[11] He is most well known for his realistic paintings of monkeys, which artistic background Patricia J. Graham suggests allowed him to bring an element of playfulness to the religious subject matter of Shussan Shaka.