Siege of Badajoz (1812)

Enraged at the huge number of casualties they suffered in seizing the city, the troops broke into houses and stores consuming vast quantities of alcohol with many of them then going on a rampage, threatening their officers and ignoring their commands to desist, and even killing several.

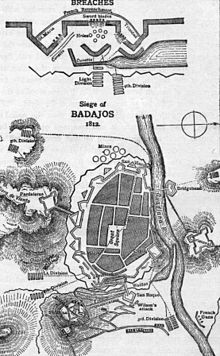

[a][6] After the allied campaign in Spain had started with the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo and the capture in earlier sieges of the frontier towns of Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo, Wellington's army moved south to Badajoz to capture this frontier town and secure the lines of communication back to Lisbon, the primary base of operations for the allied army.

Badajoz was garrisoned by some 5,000 French soldiers under General Armand Philippon, the town commander, and possessed much stronger fortifications than either Almeida or Ciudad Rodrigo.

[7] The allied army, some 27,000[2] strong, outnumbered the French garrison by around five to one and after encircling the town on 17 March 1812, began to lay siege by preparing trenches, parallels and earthworks to protect the heavy siege artillery, work made difficult by a week of prolonged and torrential rainfalls, which also swept away bridging works that were needed to bring the heavy cannon and supplies forward.

[9] By 25 March batteries were firing on the outwork, Fort Picurina, which that night was stormed by 500 men and seized by British troops from Lieutenant-General Thomas Picton's 3rd Division.

The British and Portuguese surged forward en masse and raced up to the wall, facing a murderous barrage of musket fire, complemented by grenades, stones, barrels of gunpowder with crude fuses and bales of burning hay to provide light.

[14] The furious barrage devastated the British soldiers at the wall and the breach soon began to fill with dead and wounded over whom the storming troops had to struggle.

[15] The 5th Division, which had been delayed because their ladder party had become lost, now attacked the San Vicente bastion; losing 600 men, they eventually made it to the top of the curtain wall.

Seeing that he could no longer hold out, General Philippon withdrew from Badajoz to the neighbouring outwork of San Cristobal; he surrendered shortly after the town had fallen.

During the sack of Badajoz, numerous homes were broken into, private property was vandalized or stolen, civilians of all ages and backgrounds raped and many British officers trying to bring to order were shot by the men.

[19][5] Captain Robert Blakeney wrote: The infuriated soldiery resembled rather a pack of hell hounds vomited up from infernal regions for the extirpation of mankind than what they were but twelve short hours previously – a well-organised, brave, disciplined and obedient British Army, and burning only with impatience for what is called glory.

Ian Fletcher argues: Let us not forget that hundreds of British troops were killed and maimed by the fury of the respective assaults, during which men saw their comrades and brothers slaughtered before their very eyes.

[26] In a letter to Lord Liverpool, written the following day, Wellington confided: The storming of Badajoz affords as strong an instance of the gallantry of our troops as has ever been displayed.

[27]From an engineering view point, the requirement to undertake the assault in a hasty manner, relying upon bayonet charges, rather than scientific methods of approach, undoubtedly resulted in heavier casualties, as did the lack of a corps of trained sappers.