Siege of Calais (1940)

The Germans tried several times to persuade the garrison to surrender but orders had been received from London to hold out, because an evacuation had been forbidden by the French commander of the northern ports.

Next day, small naval craft entered the harbour and lifted about 400 men, while aircraft of the RAF and Fleet Air Arm dropped supplies and attacked German artillery emplacements.

In 1966, Lionel Ellis, the British official historian, wrote that three panzer divisions had been diverted by the defence of Boulogne and Calais, giving the Allies time to rush troops to close a gap west of Dunkirk.

In 2006, Karl-Heinz Frieser wrote that the halt order issued to the German unit commanders because of the Anglo-French attack at the Battle of Arras (21 May) had a greater effect than the siege.

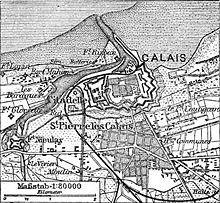

Surrounding the town was an enceinte, a defensive fortification, which originally consisted of twelve bastions linked by a curtain wall, with a perimeter of 8 mi (13 km), built by Vauban from 1667 to 1707.

Within a few days, Army Group A (Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt) broke through the French Ninth Army (General André Corap) in the centre of the French front near Sedan and drove westwards down the Somme river valley, led by Panzergruppe Kleist comprising XIX Armee Korps under Generalleutnant Heinz Guderian and the XLI Armee Korps (Generalleutnant Georg-Hans Reinhardt).

[8] Late on 21 May, Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) rescinded the halt order; Panzergruppe Kleist was to resume the advance and move about 50 mi (80 km) north, to capture Boulogne and Calais.

[11] On 19 May, Lieutenant-General Douglas Brownrigg, the Adjutant General of the BEF, appointed Colonel Rupert Holland to command the British troops in Calais and to arrange the evacuation of non-combatant personnel and wounded.

[22] SS City of Canterbury with the 3rd RTR tanks arrived from Southampton at 4:00 p.m. but unloading was very slow, as 7,000 imp gal (32,000 L) of petrol had been loaded on deck and had to be moved using only the ship's derricks, as a power cut had immobilised the cranes on the docks.

[30] On 23 May, the threat to the German flanks at Cambrai and Arras had been contained and Fliegerkorps VIII (Generaloberst Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen) became available to support the 10th Panzer Division at Calais.

Flying from forward airfields at Monchy-Breton, Hauptmann (Captain) Wilhelm Balthasar led JG 1 against the British Spitfires and claimed two of the four from his unit but lost one pilot killed.

Other units of the 1st Panzer Division moving on Gravelines met about fifty men of C Troop, 1st Searchlight Regiment at Les Attaques, about 3 mi (5 km) south-east of Bastion 6 in the Calais enceinte.

[37] When Nicholson had arrived in Calais in the afternoon with the 30th Infantry Brigade, he had discovered that the 3rd RTR had already been in action and had considerable losses, and that the Germans were closing on the port and had cut the routes to the south-east and south-west.

Nicholson moved some troops from the defence perimeter to guard the Dunkirk road, while the convoy assembled but the 10th Panzer Division arrived from the south and began to bombard Calais from the high ground.

[39] At 11:00 p.m. the 3rd RTR sent a patrol of a Cruiser Mk III (A13) and three light tanks to reconnoitre the convoy route, which ran into the 1st Panzer Division roadblocks covering the road to Gravelines.

Two mines were blown up by 2-pounder fire and the rest dragged clear, the tanks then becoming fouled by coils of anti-tank wire, which took twenty minutes to cut free.

The tanks then drove on and reached the British garrison at Gravelines but the radio in the A13 failed to transmit properly and Keller received only garbled fragments of messages, suggesting that the road was clear.

The harbour control staff ordered the wounded to be put aboard the ships, which were still being unloaded of equipment for the infantry battalions and rear echelon of the tank regiment.

Lambertye refused to go, despite being ill, and asked for volunteers from the 1,500 navy and army personnel to stay behind, about fifty men responding despite being warned that there would be no more rescue attempts.

[52] During the night, Vice-Admiral James Somerville crossed from England and met Nicholson, who said that with more guns he could hold on for a while longer and they agreed that the ships in the port should return.

[57] Major A. W. Allan, the second-in-command of 1st RB, took over the battalion which then made a fighting withdrawal northwards through the streets, to the Bassin des Chasses, the Gare Maritime and the quays.

[58] The units of the RB and QVR withdrawing from the northern part of the enceinte gained a respite when German artillery mistakenly shelled their own troops (II Battalion, Rifle Regiment 69) who were forming up in a small wood to the east of Bastion No.

At 8:00 a.m. Nicholson reported to England that the men were exhausted, the last tanks had been knocked out, water was short and reinforcement probably futile, the Germans had got into the north end of town.

Major Allan, in command, held on in the belief that the 2nd KRRC might withdraw north-east to the Place de Europe to make a joint final defence of the harbour.

The occupants of the Citadel realised that the German artillery had ceased fire and found themselves surrounded around 3:00 p.m.; a French officer arrived, with news that Le Tellier had surrendered.

[72] During the day, the RAF flew 200 sorties near Calais, with six fighter losses from 17 Squadron, which attacked Stuka dive-bombers of StG 2, claimed three, a Dornier Do 17 and a Henschel Hs 126.

In Erinnerungen eines Soldaten (1950, English edition 1952), Guderian replied to a passage in Their Finest Hour (1949) by Winston Churchill, that Hitler had ordered the panzers to stop outside Dunkirk in the hope that the British would make peace overtures.

[77] In 1966, Lionel Ellis, the British official historian, wrote that the defence of Calais and Boulogne diverted three panzer divisions from the French First Army and the BEF; by the time that the Germans had captured the ports and reorganised, III Corps (Lieutenant-General Ronald Adam) had moved west and blocked the routes to Dunkirk.

Most of the BEF and the French First Army were still 62 miles (100 km) from the coast but despite delays, British troops were sent from England to Boulogne and Calais just in time to forestall the XIX Corps panzer divisions on 22 May.

British troops on the eastern jetty called out and shone torches, which were seen by the crew; Gulzar turned back, the fugitives jumped aboard as the yacht was still under fire and escaped.